I first met Aaron Cobb online when he shared his eulogy for his son Samuel. Since then, we have corresponded every so often, and I was very glad when he told me he had decided to put his reflections about Samuel into a book. When I finished reading the manuscript of Loving Samuel, I wrote: "'A gift more precious and sweet than it was bitter.'. . . As readers, we are invited to walk through the precious, the sweet, and the bitter moments of love and loss and learning. Like Henri Nouwen before him, Cobb's measured prose, his honest and careful thinking, and his theological and emotional reflections combine to make this a book worth reading more than once." I am grateful to Aaron Cobb for offering this short reflection here today as he continues to consider the wounds and the grace experienced in the wake of Sam's death:

I did not set out to write a book about our son Samuel. I began writing because I needed to give voice to thoughts about a prognosis that promised only sadness. Diagnosed in utero with Trisomy 18 and a range of associated anomalies, Sam's fate was sealed. Like most children with Trisomy 18, if he made it to birth, it was virtually certain that he would die before his first birthday. After absorbing the initial shock, I began to document the cycles of fleeting and disappointed hopes, the plodding stretch of time in which we anticipated his birth and death (we could never be certain which would be first), and the depth of our love for him. I wrote because I had to process the questions that were filling the silent spaces. "Sorrow," C.S. Lewis writes, "needs not a map but a history" (A Grief Observed). Loving Samuel: Suffering, Dependence, and the Calling of Love is the history of our sorrow. But it is more than this. It is the living history of a love buried at the center of our sorrow.

Sam was officially diagnosed with Trisomy 18 in September 2011. We spent the next three months living through the motions of our daily routine, trying to keep some level of normalcy for ourselves and for our four-year-old son. We saw Alisha's obstetrician every week for the final fourteen weeks of the pregnancy to hear a heartbeat or to capture an image in an ultrasound. My wife carried Samuel knowing that this was likely the only time she would have to hold him. In the evenings, we sat together talking about the ordinary stuff of life, the mixture of kind or careless words we had heard that day, and the meaning of our faith.

In quiet moments—often late at night and alone—I wrote. Although my writing was personal, it was never completely private. Early in the midst of our journey, I began to share some inchoate thoughts with family and friends. What began as an expedient way to let others know how we were coping became an opportunity to invite others into our thoughts about Samuel, our love for him, and our halting attempts to endure. Making my words public afforded a space to share with others how they could offer comfort and solidarity.

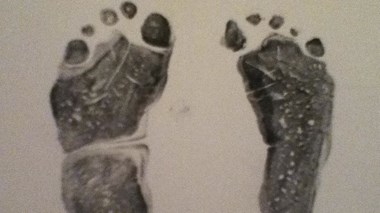

Sam's footprints

And then, late in the evening on January 1, 2012, Samuel graced us with his presence. Tucked away in a corner of a neonatal intensive care unit, we experienced five of the most significant hours of our lives together. There was a pause. We were no longer anticipating the awful, stinging sadness of losing our son; instead, we were experiencing the joy of cradling him in our arms. Our anxieties and sadness gave way to peace—a peace the world can neither give nor fathom.

Our calling to welcome Samuel was both profound and unmistakable. But in the days and weeks that followed his death I began to have a nagging sense of uncertainty. What were we to do next? How were we supposed to understand, let alone incorporate, this transformative experience? Nearly six months after Sam's death, I met with a mentor and friend from my time as a graduate student in philosophy at Saint Louis University, Father John Kavanaugh, S.J.. What began as a conversation about our respective academic work quickly became a dialog about trust and love in the midst of adversity. This conversation was a gift; it revealed to me that writing about Sam was part of what it meant to fulfill my vocation. As a father, it was a way to communicate my love for Sam; as a scholar, it was a way to give witness to important truths concerning the human condition. Shortly after our conversation, I decided to gather my thoughts into a book.

And now the finished product is sitting next to me on my desk. It is a narrative of our story that gives way to sustained reflections on the human condition and fragmented expressions of grief. It is a remembrance, a lament, and an offering of hope—hope that suffering is not the last word, that dependence is both gift and grace, and that love abides. I am a different person than when I first began writing about Samuel. Writing has changed me. It has forced me to reflect deeply on both the sorrow and the joy of our experience. I cannot separate the wounds from the grace; they are entangled.

Sitting here staring at a completed work, I wrestle with the fact that our work of love is unfinished. When a child is born, a parent longs to fill the child's life with love. In the short five hours we had with Sam, we talked to him, studied him, sang to him, introduced him to friends, and called our family on the phone so that they could hear his sweet voice. All of this follows a pattern typical for many parents sharing news of a birth. But with Sam, his death interrupted every other imaginable opportunity to pour love into his life. His death brought to conclusion only the fearful anticipation of sadness. It left a remainder of love. And it is a love reserved for him; there are no replacement children. Now, so much of my labor as a father feels unfinished and incomplete.

But when I dwell on the long, difficult days of waiting for his birth, when I consider the joy of welcoming him, when I think about the moments holding and studying his frame, when I reflect on his life and death, when I ponder our grief, and when I write it all down, I find within me this weighty sense that I am completing a work to which I have been called. If sorrow needs a history, then ours is the ongoing history of an unfinished work of love.

Aaron D. Cobb is the author of Loving Samuel: Suffering, Dependence, and the Calling of Love. Aaron and his family live in Montgomery, Alabama where he is an assistant professor of philosophy at Auburn University at Montgomery. To read more of Aaron's ongoing reflections on Samuel, follow the Loving Samuel Facebook page or Aaron's blog.

Support our work. Subscribe to CT and get one year free.