An Object Can Be Worth 10,000 Photos

Why I pursued 3D printing for Dallas Theological Seminary. /

When you first heard the “Parable of the Ten Virgins” in Matthew 25, what kind of lamp did you imagine the women holding?

Until recently, I had always pictured a curvy golden one like the genie’s lamp from Disney’s Aladdin. Imagining the women holding those big lamps in both hands, I always wondered why the five wise women couldn’t share a little of their oil with their unprepared friends. Then recently I met with Mark Bailey, president and professor at Dallas Theological Seminary, and he showed me an authentic first-century oil lamp that had been donated to the seminary. Instead of the smooth, impressive lamp I had pictured, he handed me a humble, rough little object not much bigger than a deck of playing cards.

Cradling the tiny lamp in my hand, it dawned on me that it could only hold a few ounces, and it would be almost impossible to share oil from one lamp to another. In that moment, I imagined myself as one of the waiting women that night, and I could feel the weight of Jesus’ admonition to be prepared for the bridegroom’s arrival.

After Inkjets and Factories

What if the next time you were teaching Matthew 25, there was a simple, cost effective way of recreating the experience I had for your church or class? Sure, you could just show an image of the lamp on a screen. But in today’s world, images are cheap, while grounded, tangible experiences are hard to come by. In the not-too-distant future, offering this kind of encounter with the world of Scripture is one of the promises of 3D printing.

Technically, 3D printing (also known as additive manufacturing) is not a new technology. In most traditional manufacturing, products are created by using molds filled with plastic or other materials. This is great for mass producing products, but it’s less helpful when you just need a single, custom object like a prosthetic hand or a replacement part. So in the 1980s, engineers began experimenting with new tools that functioned like an inkjet printer. But instead of dropping ink on a page, these printers dropped tiny bits of material and kept building up layers until they formed an entire object. Over the past few decades, dozens of new techniques and materials have been created allow for variations in size, color, and strength.

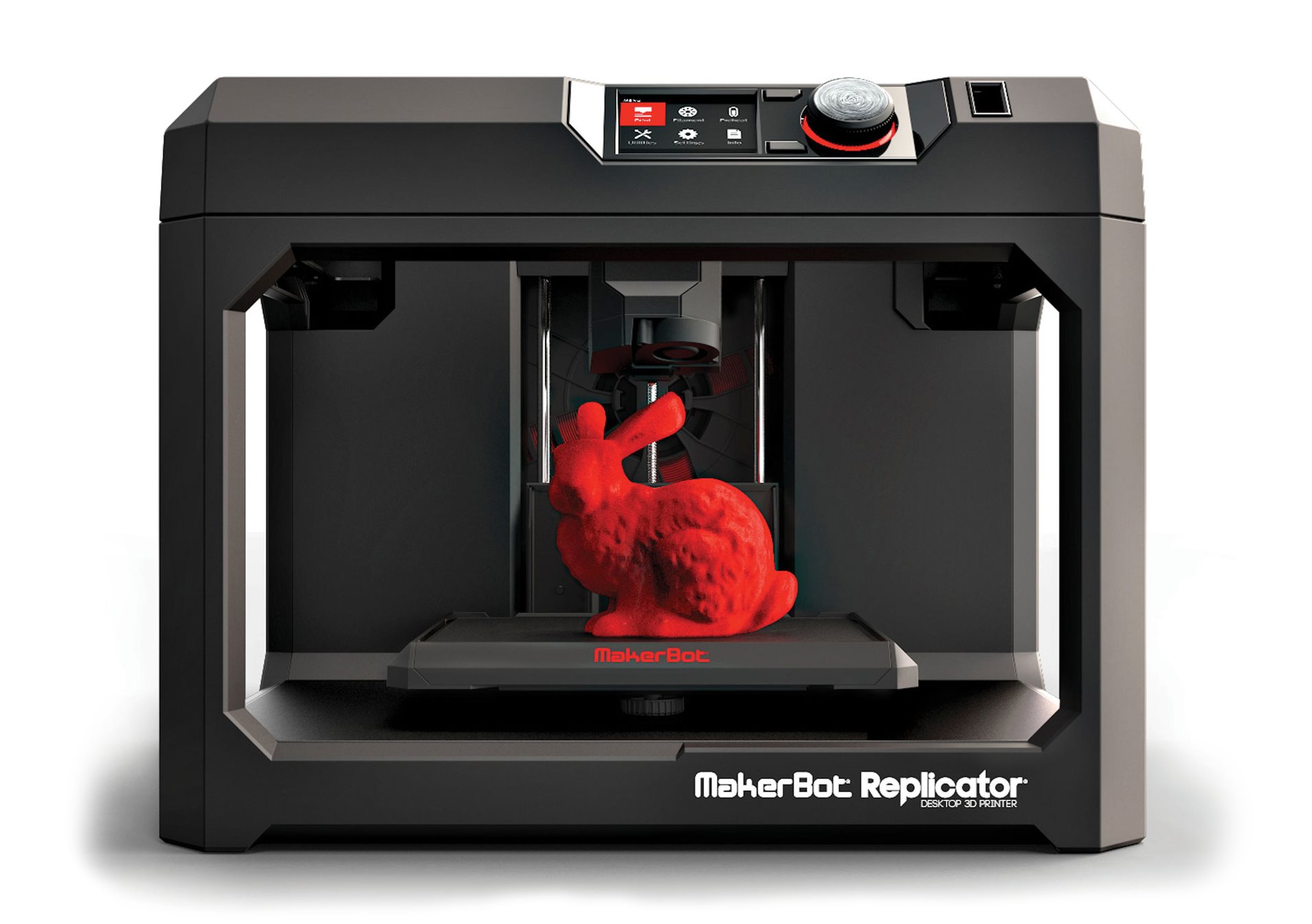

An industrial grade 3D printer can run upwards of $50,000, but the cost of consumer 3D printers has come down significantly in recent years. You can pick up a very basic model like the XYZprinting da Vinci Junior 1, capable of printing objects up to six inches long, high, and deep, for $299 at Walmart. The slightly more capable fifth-generation MakerBot Replicator Desktop 3D Printer goes for around $1,800. Online retailers advertise an authentic first-century oil lamp for around $250, and replica lamps can be purchased for around $20, but the resin needed for recreating an oil lamp might only cost around $5.

Websites like thingiverse.com have thousands of downloadable 3D models, everything from smartphone covers to dinosaur bones that you can download—many for free. You can also buy a separate 3D scanner that uses a spinning tray and an array of lasers to create a computer model of an object you want to replicate. Once you’ve chosen the object you want to duplicate, you simply put your desired color of resin into the 3D printer, send the model to printer, wait several hours, and behold—there’s your model.

Of course, it’s not quite at a Star Trek replicator level yet. Consumer models can only print monochromatic plastic objects, and they must have a self-supporting structure. That means our first-century oil lamp would be need to very carefully modeled for it to be 3D printable, and we’d be limited to colors of filament our printer can handle. But as the technology evolves, some thinkers believe 3D printing will kick off a kind of third industrial revolution where consumers no longer buy items at a store and will instead purchase 3D blueprints online that they print at home. That may be a few years off, but people around the world are already finding new and novel ways to use 3D printing.

Reprinting the Museum

Museums and archeologists have already begun using 3D printing and scanning to replicate existing historical objects and to create replacement parts for damaged, fragile, or incomplete artifacts. For example, almost every dinosaur skeleton you see in a museum has several parts that were created by hand to fill in the gaps where bones were missing. Museums are now printing these missing links using 3D printers, and they are scanning the existing bones and making them available to download and print at home.

At the Smithsonian Institute’s X 3D website, you can download everything from the tiny Eulaema bee to Abraham Lincoln’s head to a giant woolly mammoth (they offer both a life-size model and the much more printable 1/35 size). The British Museum in London has also published models of their ancient artifacts and artwork. Even if you don’t have a 3D printer, you can go online and interact with these objects in a simulated 3D environment, making them feel a bit more real and tangible than a static image.

For biblical education, it’s not hard to imagine a world in which you can fire up your favorite Bible software or website and, when you click on a word, you would see 3D models of key objects from that era. When Jesus talks about taxes, you might see a coin with Caesar’s face. When Sennacherib attacks Jerusalem under King Hezekiah (Isaiah 36), you might find one of Sennacherib's Annals (written on something about the size of a roll of paper towels) recording his version of the events. Even though Sennacherib didn’t exactly admit he was defeated by an angel of the Lord, seeing a physical object that confirms a bit of biblical history could be a powerful experience.

Causes for Pauses

The library at Dallas Theological Seminary has a replica of one of Sennacherib's Prisms, but when I looked into having it scanned, I discovered that it wasn’t clear who would own the copyright to the object or its 3D model. Would it be the British Museum, where the originals are held? Would it be the company that produced the replica? The person who scanned the object? My enthusiasm was also slowed a bit when I realized that the printers I was initially looking into purchasing might not be able to offer the level of detail needed for printing things like Caesar’s face on a coin. I was also keenly aware of the dangers of rushing to implement a new technology. It’s too easy to create a spectacle around a technology itself, distracting us from Scripture rather than illuminating it.

And yet, looking into 3D printing reminded me that the world of the Bible is one of profound physicality. In the pages of Scripture, we find that human creativity matters deeply to God, and that even mundane, everyday objects can hold a significant place. In fact, the material universe into which the Son was incarnated matters so much that sometimes feeling the texture of a humble lamp in your hands can be the difference between lacking “ears to hear” and understanding the words of Jesus.

John Dyer (j.hn) teaches and does technology for Dallas Theological Seminary. His website yallversion.com was featured in Christianity Today’s March 2014 cover story, “Hacking the Bible.”

Also in this Issue

Issue 51 / June 23, 2016- Editor's Note from June 23, 2016

Issue 51: Our Special 3D Issue. /

- Beauty Can Be a Matter of Perspective

We were created to view the world through two eyes. /

- If Jesus Came to Flatland

How to think about dimensions beyond our own. /

- The Old West in 3D

Photos that shaped a nation’s view of its expanding horizon.

- Wonder on the Web

Issue 51: Links to amazing stuff in 3D.