Most of us would recall the early centuries of the Church as the era of persecution, when thousands of Christians became confessors or martyrs by suffering or dying for their faith at the hands of the Roman authorities.

And, in a discussion of the topic, we probably would mention the modern waves of persecution that swept over Christians under the antireligious regimes of Communist states in Eastern Europe.

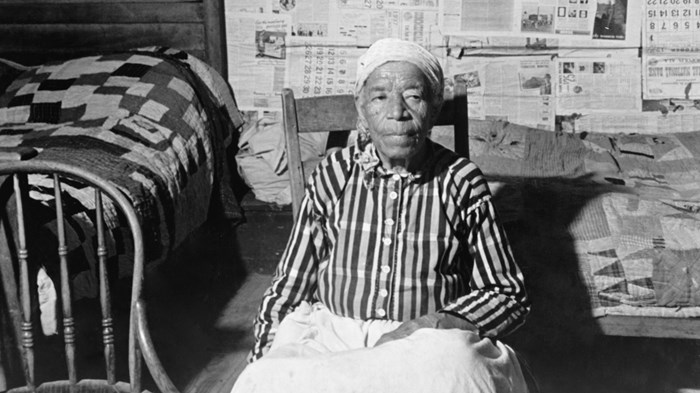

Few, I think, would identify the suffering of African-American slave Christians in similar terms, as a prime example of the persecution of Christianity within our own nation's history. And yet the extent to which the Christianity of American slaves was hindered, proscribed, and persecuted justifies applying the titles confessor and martyr to those slaves. Like their ancient Christian predecessors, they bore witness to the Christian gospel despite the threat of punishment and even death at the hands of fellow Christians.

For example, slave Christians suffered severe punishment if they were caught attending secret prayer meetings which whites outlawed as a threat to social order. And yet they endured suffering rather than forsake worship.

In 1792 Andrew Bryan and his brother Sampson were arrested and hauled before the city magistrates of Savannah, Georgia, for holding religious services. With about 50 of their followers they were imprisoned and severely flogged. Andrew told his persecutors "that he rejoiced not only to be whipped, but would freely suffer death for the cause of Jesus Christ."

Eli Johnson claimed that when he was threatened with 500 lashes for holding prayer meetings, he stood up to his master and declared, "I'll suffer the flesh to be dragged off my bones … for the sake of my blessed Redeemer."

Slaves suffered willingly because their secret liturgies constituted the heart and source of slave spiritual life, the sacred time when they brought their sufferings to God and experienced the amazing transformation of their sadness into joy.

This paradoxical combination of suffering and joy permeated slave religion, as the slave spirituals attest:

Nobody knows de trouble I see

Nobody knows but Jesus,

Nobody knows de trouble I've had

Glory hallelu!

The mystery of their suffering took on meaning in the light of the suffering of Jesus, who became present to them in their suffering as the model and author of their faith. If Jesus came as the suffering servant, the slave certainly resembled him more than the master.

One source that sustained Christian slaves against temptations to despair was the Bible, with its accounts of the mighty deeds of a God who miraculously intervenes in human history to cast down the mighty and to lift up the lowly, a God who saves the oppressed and punishes the oppressor. One biblical story in particular fired the imagination of the slaves and anchored their hope of deliverance: the Exodus.

Questioned by her mistress about her faith, a slave woman named Polly explained why she resisted despair: "We poor creatures have to believe in God, for if God Almighty will not be good to us some day, why were we born? When I heard of his delivering his people from bondage I know it means the poor African."

In the midst of dehumanizing conditions so bleak that despair seemed the only appropriate response, African Americans believed that God would "make a way out of no way." Enslaved, they predicted that God would free them from bondage. Impoverished, they asserted that "God would provide." Their belief in God did not consist so much in a set of propositions as it did in a relationship of personal trust that God was with them: "He will be wid us, Jesus, be wid us to the end."

Compassionate humanity

We might expect that their identification with the biblical children of Israel, with Jesus, and with saints and martyrs might have pushed the slaves toward self-righteousness and racial chauvinism. Instead it inspired compassion for all who suffer, even occasionally for their white oppressors.

William Grimes, for example, a slave who refused to lie or to steal, was unjustly accused and punished by his master. "I forgave my master in my own heart and prayed to God to forgive him and turn his heart," Grimes reported.

When slaves forgave and prayed for slaveholders, they not only proved their humanity, the also displayed to an heroic degree their obedience to Christ's command "Love your enemies. Do good to those who persecute and spiritually use you."

Christianity taught the slaves that God had entered into the world and taken on its suffering, not just the regular suffering of all creatures that grow old and die, but the suffering of the innocent persecuted by the unjust, the suffering of abandonment and seeming failure, the suffering of love offered and refused, the suffering of evil apparently triumphant over good. They learned that God's compassion was so great that he entered the world to share its brokenness in order to heal and transform it. The passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus began and effected the process of that transformation.

It was compassion, the love of all to the extent of sharing in their suffering, that would continue and bring to completion the work of Christ. All of this of course is paradoxical. All of this is of course a matter of faith.

American slaves accepted that faith. And in doing so they found their lives transformed. No, the suffering didn't stop. Many died while still in bondage. And yet they lived and died with their humanity intact. That is, they lived lives of inner freedom, lives of wisdom and compassion. For their condition, evil as it was, did not ultimately contain or define them. They transcended slavery because they believed God made them in his image with a dignity and value that no slaveholder could efface.

Albert Raboteau is professor of religion at Princeton University and author of Slave Religion (Oxford, 1978).

Faith and Justice

Slaves' open scorn for white religion is one of the most consistent and vehement themes in their narratives. The idea of a "good Christian slaveholder" was a moral impossibility.

The enslaved black Christians were especially critical of white preachers, many of whom were hired by plantation owners to preach a religion that sanctioned slavery. The southern white evangelical defense of slavery on biblical grounds was a joke. No elaborate polemics or moral arguments were required to convince black Christians to unmask the evils of slavery and racial prejudice.

The most important lesson for black Christians today is to discern that our enslaved spiritual ancestors maintained the vital link between spiritual formation and social ethical transformation in the quest for justice and freedom.

The most important lesson for white Christians is to acknowledge the error and futility of trying to separate spirituality from social ethics, based on wrongful interpretations of the Bible and contrived to preserve racial privilege and deny responsibility for the pursuit of racial justice in both church and society.

Cheryl Sanders is professor of Christian ethics at Howard University School of Divinity, senior pastor of Third Street Church of God, Washington, D.C., and author of Empowerment Ethics for a Liberated People (Fortress, 1995).

Need for Community

The black church has provided a place of unity and cohesion for the black community. It is one of the only institutions that we have always had some control over. Even in the slave quarters, religion and the church were instruments God used to maintain a semblance of neighborhood and community.

Though I agree with integration, I also think it is one of the worst things to have happened to the black community. The moment we were able to assemble where we desired, we lost the continuity that made us a community and began to assimilate into the broader culture. In so doing, we lost a lot of what it meant to be African-American and Christian.

The church was the centrifugal force of the black community. In the 1920s, '30s, and '40s, many the individuals who were successful in the music industry had the roots in the black church. Likewise, a number of black athletes also attribute their initial encounters with sports to church-organized athletics.

The only way that the church will be able to recapture its vitality is to reassess its role as the spiritual fountain from which the black community can once again drink freely. We have made significant strides in the arenas of politics, societal acceptance, and the like. But we have lost our edge as the place to build the lives of our people in a holistic manner.

I see so many young blacks who express a limited sense of God consciousness. I remember when I was younger and coming up, there was a certain level of respect that was afforded our elders. If we were playing marbles and were approached by someone coming from church, we immediately made room for them and even stopped what we were doing until they passed by. Not so today. Our youth have a limited understanding of the Spirit and of the place that the church plays in the very survival of the community.

My contention is that the black church must diligently seek to re-emerge as the fuel for the community if it is to be taken seriously in the new millennium.

Robert L. Stevenson Jr. is director of research for the Los Angeles Black Church History Project at Fuller Seminary.

Copyright © 1999 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History Magazine.

Click here for reprint information on Christian History.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month