With his 1949 Los Angeles crusade fast approaching, Billy Graham was the one in need of revival. Outwardly his career seemed to be on the upswing. Two years earlier at age 29, Graham became the youngest university president in America when he succeeded fundamentalist patriarch William Bell Riley at Northwestern Schools in Minneapolis. Now after a number of successful smaller crusades, he readied for his biggest challenge yet—Los Angeles

Yet inwardly Graham's faith wavered. Reading Reinhold Niebuhr and Karl Barth, he began to question the "old-time gospel" he embraced as a young man. At issue was nothing less than the reliability of Scripture. The Bible's seeming contradictions haunted Graham.

"I was not a searching sophomore, subject to characteristic skepticism," he said of the awkward timing of his doubts. "I was the president of a liberal arts college, Bible school, and seminary—an institution whose doctrinal statement was extremely strong and clear on this point."

The duo divided

While shaken by the neo-orthodoxy of Niebuhr and Barth, Graham was much more severely disturbed by the doubts of his evangelist friend, Charles Templeton. During the 1940s Templeton and Graham were Youth for Christ's dynamic duo. Though Graham routinely induced better results with his altar calls, Templeton was widely considered the more gifted preacher. Handsome, suave, intelligent, and charismatic, Templeton lacked only a formal education to validate these talents.

So in 1948 he decided to enroll at Princeton Theological Seminary and invited Graham to join him. Graham acknowledged his own lack of education—this university president had only a Wheaton College bachelor's degree—but he balked at Princeton's liberal reputation. He made a counteroffer: "Chuck, go to Oxford and I'll go with you."

But Templeton had his eyes set on Princeton alone. The following winter they met in New York City to discuss Templeton's first semester. Princeton clearly had a profound impact on Templeton.

"Billy, you're 50 years out of date," Templeton prodded. "People no longer accept the Bible as being inspired the way you do. Your faith is too simple. Your language is out of date. You're going to have to learn the new jargon if you're going to be successful in your ministry."

Templeton's training in theological liberalism exposed Graham's intellectual shortcomings. But Graham was not prepared to surrender just yet. "Chuck, look, I haven't a good enough mind to settle these questions," Graham said with characteristic humility. "The finest minds in the world have looked and come down on both sides of these questions. I don't have the time, the inclination, or the set of mind to pursue them. I have found that if I say, 'The Bible says' and 'God says,' I get results. I have decided I am not going to wrestle with these questions any longer."

Templeton's instinct for persuasion kicked in. "Bill, you cannot refuse to think," he chided. "To do that is to die intellectually. You cannot disobey Christ's great commandment to love God 'with all thy heart and all thy soul and all the mind!" Not to think is to deny God's creativity. It is to sin against your Creator. You can't stop thinking. That's intellectual suicide."

Foothills of faith

Despite his assertion to the contrary, doubt continued to haunt Graham. In August, Christian educator Henrietta Mears invited him to address an audience at her Forest Home retreat center, located east of Los Angeles. Graham's shaken faith gave him pause, but he nonetheless obliged.

Mears was a phenomenon in Southern California's celebrity culture. Impeccably dressed, jewel-adorned, and wealthy, she grew up in William Bell Riley's Minneapolis church. After moving west, Mears transformed First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood's Sunday school program, increasing enrollment from 450 to 4,500.

While he prepared to speak at Forest Home, Graham and Mears spoke about his doubts. She understood liberal theology. But unlike Templeton, she found the arguments unconvincing. The ease and authority with which she wielded Scripture comforted Graham.

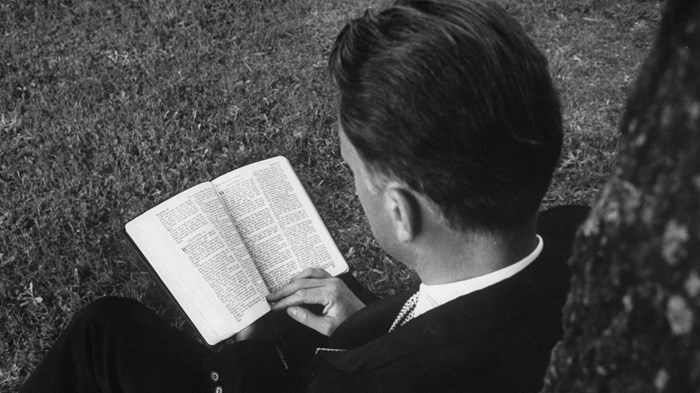

Still, many of Graham's questions remained unanswered. Did Noah actually build an ark to survive a great flood? Could a whale really have swallowed Jonah? Pondering these miracles, Graham roamed into the foothills of the nearby San Bernardino Mountains. With the moon shining, he wandered off the trail, opened his Bible on a tree stump, and took his concerns to God. Inexplicably, the burden lifted.

"Father, I am going to accept this as thy Word—by faith!" Graham proclaimed. "I'm going to allow faith to go beyond my intellectual questions and doubts, and I will believe this to be your inspired Word."

Tears streaming down his face, Graham returned to Forest Home. Though he didn't have an explanation for every biblical oddity, for the first time in months he felt powerful intimacy with God and renewed confidence in the Scripture he proclaimed.

The road not taken

As for Templeton, he finished his graduate work at Princeton, then became an evangelist for the National Council of Churches. Princeton's dean even considered him "the most gifted and talented young man in American today for preaching mission work." But it wasn't long before Templeton admitted that he no longer believed in any sort of meaningful Christianity. He left the NCC and ultimately moved to Toronto where he became a prominent media personality, writing newspaper columns and providing television commentary.

For much of his life he remained friends with Graham, but Templeton never returned to the faith of his youth. Just two years before his death in 2001, he published a critique of Christianity titled Farewell to God: My Reasons for Rejecting the Christian Faith.

Graham's life needs no such explanation. Mere months after his breakthrough in the mountains, Graham's Los Angeles crusade made him a household name in America and launched an extraordinary evangelistic career. Today a simple bronze plaque marks the spot where Graham submitted once and for all to the authority of Scripture.

Copyright © 2004 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History & Biography magazine.

Click here for reprint information on Christian History & Biography.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month