Last week, we went way behind the news and gave our top ten reasons why—when today's news seems more pressing than ever—we should read the history of the church at all.

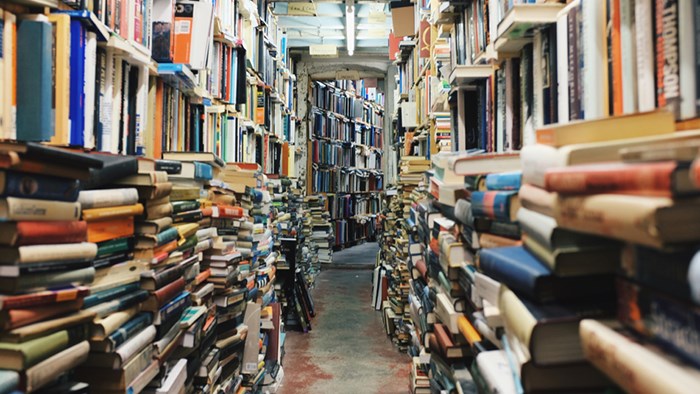

Ten good reasons, however, are not enough, even with the best of intentions. With hundreds of thousands of books out there, we need to know where to start. Which is just what we've got this week: ten great Christian history "starter books."

These are not books written by modern historians. They are that more exciting, though sometimes more difficult, thing—primary documents. Written by folks "on the ground," right in the midst of events, these are the front line reports of the church through two millennia. And they make for riveting reading, unveiling in a fresh and compelling way what God has done for his people.

Here, then, are our top ten Christian history starter books. For an anchor against the current media "war blitz," pick one that matches your interests and begin reading. Such reading is not an escape—it's a way of girding up, in faith, for whatever news tomorrow will bring. History shows this, if nothing else: those who are rooted in the centuries are less likely to topple in the storms of the present.

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History

I get chills reading this. If you have ever wondered what happened to the church in the decades and centuries after the apostles, this is your book. In fact, there is simply no other history of the church written so close to these early centuries. Eusebius (260-340) cites hundreds of precious early documents that he had personally seen, and many of them are long gone. These colorful pages often have the feel of a first-hand account, because Eusebius's sources were really there, living, breathing, "spreading the flame." The edition linked above even includes a "Who's Who in Eusebius," to help you find your way through the names. (Another edition is available for free online at the Christian Classics Ethereal Library.)

Augustine, Confessions

Here is the granddaddy of all biography. Augustine (354-430) was an expert rhetorician, and all of his art goes into this book. He is brutally frank about his own struggles with sexual sin. He is also penetratingly insightful on the nature of sin and faith. Written as a long prayer of thanksgiving to the God who saved him, this is truly a riveting read. You may be tempted to skip through his occasional philosophical meanderings on topics like the origin of the soul or the nature of time and eternity. But even these help complete the portrait: Augustine was a deep, devoted thinker who lived out his motto Crede, ut intelligas ("Believe in order that you may understand"). There are many, many translations of the Confessions. I happen to like the lively, intimate one of Maria Boulding, linked above. (But if you want a free version, the Christian Classics Ethereal Library has two translations. Another is available online here.)

If you have already read the Confessions and want to get a glimpse of what Eugene Peterson has called Augustine's "earthy, colloquial, witty, Christ-honoring sermons to his African congregation," you should pick up the new translation of some of those sermons into our contemporary idiom, Sermons to the People, translated and edited by William Griffin (OK, we're sneaking in #11).

Little Flowers of St. Francis

Clearly, some of these collected stories about the life of St. Francis of Assisi (1182-1226) are legends—or at least half-legends built on kernels of fact. Yet even these have the ring of truth. With or without the legends, Francis was a truly remarkable man, as Christlike as any who has lived. And beyond the man himself, we get a sense from this loving contemporary account of the intensely visual and mystical piety of the thirteenth-century friars. Levitations, prostrations, visions of holy fire, words of knowledge—this was a rockin' charismatic church, folks! (Here's the CCEL's older translation.)

Protestant Reformation (Hillerbrand)

A discouraging number of Reformation documents record sparring matches over the details of such admittedly important things as the practice and meaning of the Eucharist. But Luther and his Protestant friends (and enemies) published much, also, of a more gripping sort. Here, between two covers, you will find Luther's Freedom of a Christian Man (theologically momentous and intensely devotional at the same time) and his commentary on Galatians; Calvin's famous "Reply to Sadoleto"—laying out the principles of the Reformation—and his "Ecclesiastical Ordinances" of Geneva; and writings by Zwingli, various Anabaptists, and English Reformers as well.

St. Benedict of Nursia, The Rule of St. Benedict

if you've ever wanted to know how monasteries and convents have really looked through the centuries, from "within" the intense dedication and piety of their inhabitants, then this is a must read. Though Christian monasticism had already been around for centuries when he wrote it, St. Benedict's (ca. 480 – ca. 547) brief rule set the parameters for almost all Western monastic communities to follow. It's not a long read—only slightly more than 100 paperback-sized pages in the edition linked above. The advice here is concise, moderate, and shows a deep understanding of human character and personality.

This edition also provides a brief historical summary of the development and spread of Christian monasticism, a sketch of St. Benedict's life, and a few learned but accessible pages on how the Rule was implemented and on its impact on religious orders—and indeed on Western culture—from the Middle Ages to the present. (CCEL has a free version of the rule without the context.)

Teresa of Avila, Interior Castle

When I first read this book by the Counter-Reformation Spanish mystic Teresa of Avila (1515-1582), I finally understood why so many committed, leading Protestants go to the Roman Catholic tradition to find spiritual advice. Quite simply, no one has done spirituality better (though I'd give some of the Puritans a close second). In this winsome book, Teresa provided a clear, sensible account of what the faithful soul must do—and just as important, what it must leave to God—as it seeks to be transformed from an imperfect, sinful creature into the spiritual bride of Christ. She acknowledges that that transformation is never complete short of heaven. Then she takes us on a rich interior voyage, filled with penetrating insights into the ways God deals with the soul beset by sin. (Here's a free translation.)

Philip Jacob Spener, Pia Desideria

Within a century of Martin Luther's death, many of his heirs in German Lutheranism were spending more time wrangling over theology than living the Christian life Luther had so passionately embodied. Theological schools were filled with dissipated youth put there by parents who sought a comfortable living and societal status for their kids through Christian ordination. Christian groups were too busy sniping at each other to evangelize the lost. In short, "dead orthodoxy" reigned. Enter Philip Jacob Spener (1635-1705) and his Pietist friends. Spener's book was the manifesto that began the Pietist movement—to which the later evangelicalism of John Wesley and Jonathan Edwards would owe so much. Intensive Bible reading, small groups, spiritual disciplines, reform of theological education—these are just a few of the reforms Spener proposed. His irenic tone and evident piety made this a classic still worth reading today.

Jonathan Edwards, Religious Affections

I first encountered Edwards's (1703-1758) Religious Affections in 1985, while pursuing a religious studies degree in Canada. It spoke to me as no other book. At the time, I was attending an independent charismatic church, and it seemed to me that Edwards, though really addressing folks caught up in the Great Awakening of the 1740s, was speaking to the folks sitting in the pew with me—or dancing in the aisles. Only problem: its insights into religious experience were written in eighteenth-century prose by a philosopher whose observations, though clear and penetrating, can run to the lengthy. "If only," I thought "someone would make this great stuff available in a modern edited version!"Â An updated summary is Gerald R. McDermott, Seeing God: Twelve Reliable Signs of True Spirituality. Or you can dive right in with the version linked above—or one of the several formats available at CCEL.

Peter Cartwright, Autobiography

if Augustine invented the autobiography, Cartwright (1785-1872) made it sing. If you've ever wanted a personal, colorful window into the frontier years of camp meetings and circuit riders, there's no better place to start than this book (other than, perhaps, our issue 45: Camp Meetings and Circuit Riders). If you've seen Robert Duvall's The Apostle, you'll find here the origins of the rough-and-tumble culture that led "Junior" to take a profane heckler out of his church and punch his lights out. In these pages you'll find plenty of such exploits (and many that are more conventionally pious), told with gusto by their (invariable) hero. Though he failed (not for want of trying) to evangelize Abraham Lincoln, the Methodist evangelist Mr. Cartwright and his circuit-riding companions took Methodism from a tiny sect in 1800 to America's largest denomination by the end of that century.

Amanda B. Smith, Autobiography

There's no form like the autobiography to usher you into the life and world of the writer. This one, by an ex-slave evangelist from the nineteenth century, opens up the world of that century's holiness revival. Amanda Berry Smith (1837-1915) traveled to many of the Northeastern U.S.'s Victorian-era holiness camp meetings, where she ministered with wisdom and forcefulness to thousands of whites (and a few African Americans) who were willing to hear her as a messenger of God. She encountered racism and sexism along the way, and she is frank about her own fears about exposing herself to the ridicule of powerful Christian leaders white and (painfully) black. But the overwhelming sense we get is of a woman both entirely dedicated to her Lord and gifted by him for extraordinary ministry.

Copyright © 2003 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month