The religiously unaffiliated are on the rise.

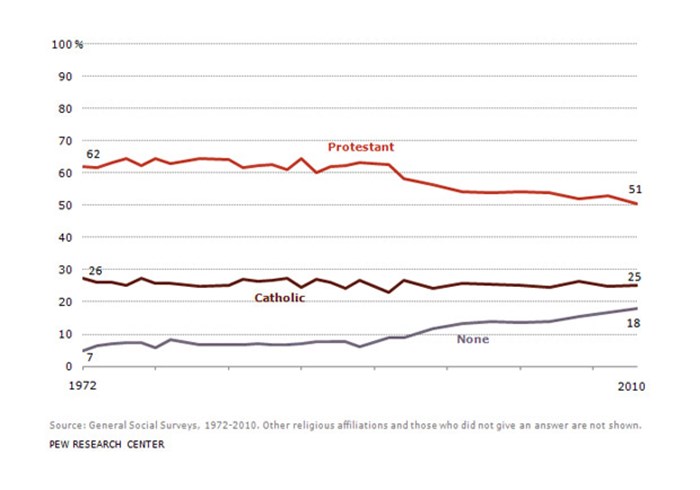

Just under 20 percent of all Americans do not identify with any particular religion, according to a Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life report released Tuesday, titled "'Nones' on the Rise." And as that share of the population, up from 15 percent in 2007, continues to rise, the study also reports that the Protestant share, including mainline and evangelical, has dipped below the 50-percent mark for the first time.

"These numbers don't in any way suggest that religion is dying out in America," said Kim Lawton, managing editor of Religion and Ethics NewsWeekly, which partnered with the Pew Forum to produce part of the report. "This is a picture of what we found, but it's not a predictor of the future."

According to the report, 53 percent of respondents said they were Protestant in 2007, but only 48 percent identified as such in 2012. The decline comes primarily from white evangelical and mainline believers, down 2 and 3 percent respectively since 2007.

Christians still compose the overwhelming majority—73 percent—of the survey's 120,000 respondents, Pew reported.

Bradley Wright, associate professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut, said the recent decline in Protestants is only symbolically significant.

"There's not very much difference between 51 and 48 percent," he said, "except if you consider that the decline is due in large part to the decline in mainline Protestants, who constituted 45 percent of the total population a century ago."

Doug Sweeney, professor of church history at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School and a member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, said mainline churches have long been aware of their declining membership.

"Somehow our children aren't catching the significance of our faith and feeling the need to stick around—until they have children and want them to be raised in a faith community," he said.

Now, nearly one-third of Americans under the age of 30 identify themselves as religiously "unaffiliated," nearly double the percentage of unaffiliated Americans in Pew's data on previous generations at the same age, Lawton said.

Michael S. Horton, professor of systematic theology and apologetics at Westminster Seminary in California, said Christians appear to be creating future "nones" by failing to adequately pass the faith on to successive generations.

"We are about a generation away from a worshiping community that is rather small in terms of those who know what they believe, why they believe, and practice their faith with some real conviction," he said.

Those whom Pew classifies as "nones" are not absent of religiosity, said Lawton. Only 2.4 percent of the American public classified themselves as atheist and 3.3 percent as agnostic.

Instead, 13.9 percent of Americans classified their religious identity as "nothing in particular," but it is wrong to describe them as "wholly secular," Lawton said.

"They don't have any official ties with religion, but many retain some beliefs or practices associated with religion," she said.

Survey results show that 68 percent of unaffiliated Americans still said they believe in God. Most interesting, Lawton said, is that 20 percent of them still said they pray on a daily basis.

Wright said this group could be referred to as the "unchurched believers," which contradicts the common misconception that the growing unaffiliated population is entirely atheist or agnostic. This reflects a shifting cultural acceptance of those who do not define themselves by their religion.

But Lillian Daniel, a United Church of Christ minister and author of the forthcoming book When "Spiritual but Not Religious" Is Not Enough, said people who describe themselves this way are the "norm in a bland, self-centered American religious landscape."

"The very idea that you can pick and choose is, in some ways, a self-centered project, looking for the spiritual 'goods' without making a commitment," she said.

Wright said it is too early to tell whether this is a generational effect or merely a reflection of age.

"Historically, people get more religious as they get older," he said. "Young people are less affiliated with every aspect of conventional society, but there are generational effects. For some people it's a more honest classification."

And Daniel said that makes it an exciting time to be a Protestant.

"We had many decades when people went to church because they felt like they had to. You get none of that now," she said. "With this freedom to choose, the people who come want to be there and there is a seriousness of purpose."

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month