Churches were divided. Believers eschewed cultural influence. Liberal modernism was on the move. Then God made Billy Graham.

Michael S. Hamilton

The first time Ruth Bell saw her future husband, he was dashing down the dormitory steps two at a time. Now there's a young man who knows where he's going! she thought. But in fact Billy Graham had no idea where he was going; no idea that he would travel the planet preaching the gospel to more people than anyone in history. Ruth's second impression, however, was spot on target: “He wanted to please God more than any man I'd ever met.” This desire, more than anything, set him apart. In an era when evangelicals lived expectantly in the shadow of the Second Coming, Billy Graham was odd in hoping the Lord would tarry: “I sure would like to do something great for him before he comes.”

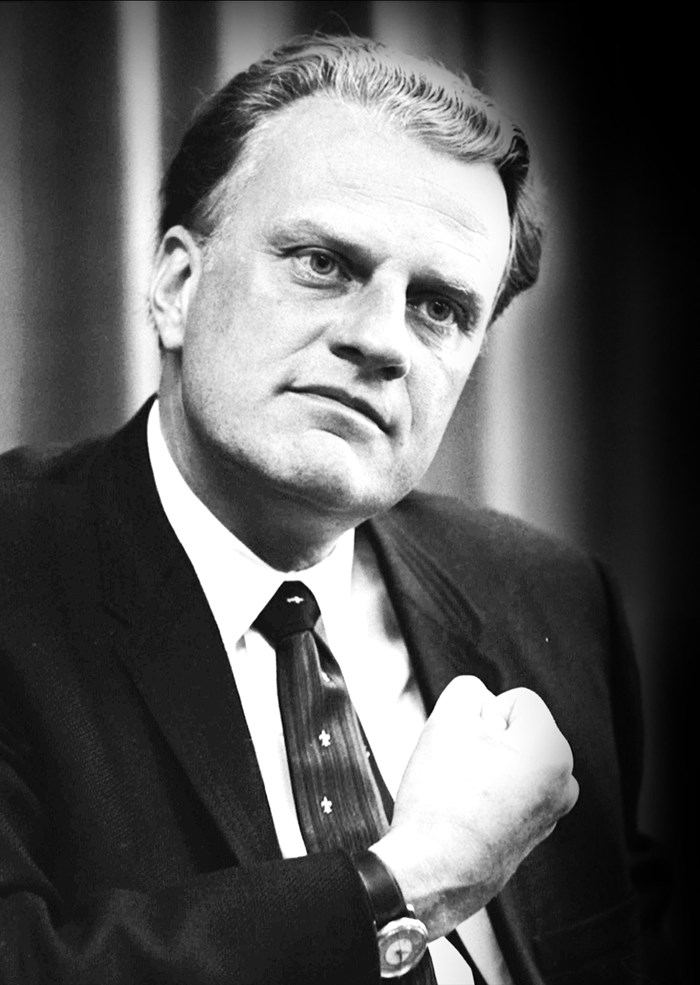

The Lord did tarry, and Graham made the most of it. If there were a Mount Rushmore for English-speaking evangelists, Graham would be the fifth in granite, alongside Whitefield, Finney, Moody, and Sunday. For the most part, it's easy to imagine why huge crowds pushed and shoved to hear them preach. George Whitefield—short and cross-eyed, with the voice of a tornado—cavorted, posed, and wept on outdoor platforms as he brought Bible dramas to life. Charles Finney had terrifying eyes that drilled out soft spots in the soul, his fiery preaching about the wrath of God going straight to the exposed nerves. Billy Sunday was charming, with jazzy suits, movie-star looks, and a smile that lit up auditoriums. But up on stage, after joking and mugging and flattering the VIPs, he would throw down his hat, rip off his tie, and jump onto the pulpit—sometimes waving a large American flag—attacking sin and beseeching sinners to come to Jesus.

Dwight Moody's appeal is harder to figure. Of grandfatherly mien, he was portly and genial. He preached less about sin and more about love. All the old drawings of him in the pulpit give the impression he must have been stolid and ponderous. Yet it was Moody—more than Whitefield, Finney, and Sunday put together—who was Billy Graham's true predecessor. It was Moody whom Graham admired; Moody who, in fact, made it possible for Graham to do what he did. For “Crazy” Moody was the architect who drew up the plans and laid the foundation for 20th-century evangelicalism. Then Billy Graham took over the project and built it to dimensions beyond any of Moody's craziest dreams. By the start of the 21st century, the Moody-Graham project had reshaped the skyline of American Christianity and had launched a new kind of ecumenical movement that reached into every corner of the globe.

Back to the Future

It's easy to forget that Billy Graham's early pulpit style owed more to Whitefield and Sunday than to Moody. He pranced and shouted until his hair was a mop. He clenched his fists, pointed his fingers like pistols, and spoke so fast that German newspapers called him “God's Machine Gun.” Graham's eyes were arresting—sharp blue, blazing out from dark sockets. His preaching, like Whitefield's, was sometimes performance art; it produced this description in 1950 by an astonished Boston reporter:

He prowls like a panther across the rostrum. ... He becomes a haughty and sneering Roman, his head flies back arrogantly, and his voice is harsh and gruff. He becomes a penitent sinner; his head bows, his eyes roll up in supplication, his voice cracks and quavers. He becomes an avenging angel; his arms rise high above his head and his long fingers snap out like talons. His voice deepens and rolls sonorously—the voice of doom. So perfect are the portrayals that his audience sits tense and fascinated.

Like Sunday, Graham's early preaching seamlessly blended God and country, most often in warnings about the threat of communism. “Either communism must die, or Christianity must die, because it is actually a battle between Christ and anti-Christ,” he said. The answer was “old-fashioned Americanism. Through the ideals of early Americanism we built the greatest nation ever to exist in all history.”

But Graham's future lay behind Sunday in territory that Moody had staked out. Moody's genius had been his ability to draw together and fuse traditional evangelical touchstones—a Bible-based, conversion-centered faith; simple preaching and popular songs; extensive publicity and self-promotion; and a restless “I-must-keep-working-for-the-Lord” style—with newer elements like dispensational premillennialism and an urgency for foreign missions. He then poured this mixture into a new institutional mold—the parachurch organization. After Moody, evangelical visionaries weren't so much churchmen as entrepreneurs launching their own non-denominational start-ups, employing lay workers to carry out highly specialized missions.

At the same time Moody was creating a new evangelical synthesis, an anti-supernatural form of Christianity calling itself modernism (or liberalism) began entrenching itself in the seminaries and headquarters of the large northern Protestant denominations. When conservatives tried and failed to push them out of these “mainline” denominations in the 1920s, the center of evangelical gravity shifted from the denominations to the parachurch network started by Moody. It turned out that the independence and non-denominational character of the parachurch gave evangelicals a tremendous advantage. They could bypass denominational leadership and go directly to the people with a simple, vibrant evangelicalism that transcended denominational differences. Billy Graham would exploit this advantage better than anyone before or since.

Critics were sure that Graham's crusades were an anachronism, the death-rattle of the bad old days of American Christianity. But they failed to see that mass-meeting revivalism was only the building's façade.

By the time Billy was a teenager, Moody-style evangelicalism had become more important to his parents than the strict Presbyterianism of their North Carolina church. His mother got dispensationalism from the parachurch network, and his father helped bring revivalist Mordecai Ham to town. After sitting under Ham's glare for several nights, Billy finally did what he would spend a lifetime asking others to do—he got out of his seat, went forward, and soberly made his decision for Christ.

When Billy was ready for college in 1936, the parachurch network provided all the options he and his parents considered. The differences between fundamentalism (which stressed doctrinal purity and attacks on liberal theology) and evangelicalism (which stressed evangelism and discipleship) were already emerging, and Billy's college experiences foreshadowed which side of the divide he would end up on. The rigidity of fundamentalist Bob Jones University turned out to be a poor fit, but Florida Bible Institute and Wheaton College—both part of the Moody network—taught him lessons he never forgot. He learned that despite denominational differences, there existed at the grassroots level of all of American Protestantism a common-denominator Bible faith to which an evangelist could appeal. At Wheaton he also encountered a student culture with little interest in attacking liberalism. Talented Wheaton graduates from that period were taking up Moody's blueprint and filling in the blanks, starting new parachurch ministries like InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, Trans World Radio, and Christian Service Brigade.

In 1943 Billy and Ruth married and took a pastorate outside Chicago, but not for long. Out on the East Coast, Wheaton alumnus Percy Crawford was cooking radio, revivalism, and youth culture into a confection that drew thousands of young people to Saturday night rallies. Evangelical entrepreneurs in other cities quickly started similar programs, calling them Youth for Christ (YFC). Wheaton alumnus Torrey Johnson brought YFC to Chicago and tapped 25-year-old Graham as his featured speaker. Crawford's flashy clothes, zippy programming, rapid-fire preaching, and “bigger-better-faster” mentality fit Graham perfectly. Within months, Johnson organized most of the nation's independent rally organizations into a single Youth for Christ International and hired Graham to be its first paid evangelist.

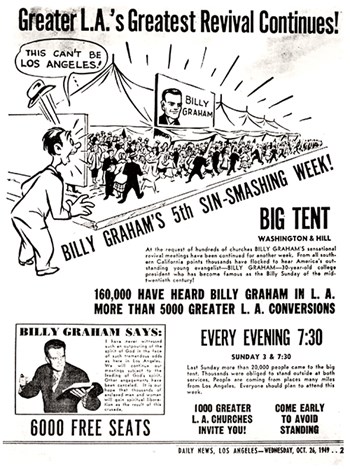

Graham hit the road and never looked back. By 1946 YFC rallies were drawing a million kids every Saturday and attention in the nation's press. Within two years Graham and his platform team of Cliff Barrows, George Beverly Shea, and Grady Wilson were holding their own revivals, little knowing that they'd be working together for the rest of their careers. After just six revival campaigns, Billy Graham—all of 31 years old—rocketed into national fame with his wildly successful eight-week crusade in Los Angeles.

Critics were sure that Graham's crusades were an anachronism, the death-rattle of the bad old days of American Christianity. But they failed to see that mass-meeting revivalism was only the building's façade. Behind that façade stood an impressive superstructure—Moody's synthesis of traditional evangelical beliefs, fresh ideas, and new institutional forms. The fundamentalist-modernist controversies had only temporarily halted construction on Moody's project. Now the laborers were back on the job, and the most important of them would prove to be Billy Graham.

Building the New Evangelicalism

Nineteenth-century newspapers turned Moody into a celebrity. He wasn't thrilled about it—he hadn't an attention-seeking bone in his body—but it was a good bargain. The newspapers needed stories; his campaigns needed publicity. The more publicity he got, the more people he could pull into his gospel lifeboat.

Billy Graham embodied the same paradox. He was a genuinely humble person who spent his long life drawing public attention to himself. Graham's parachurch organization bore his name—the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA)—and its impressive publicity efforts always centered on the evangelist himself. Ever-anxious about attendance at an upcoming crusade, Graham was known to complain, “I don't see my picture up enough.” Most of the time, Graham was blessed with excellent press coverage. In the early years it seems likely that Henry Luce, publisher of Time and Life magazines, and William Randolph Hearst, who owned a large chain of newspapers, were attracted by the anti-communism part of Graham's message. But in the main, the reasons for Graham's good relations with the press mirrored Moody's—the evangelist needed publicity, the press needed good stories.

Graham soon had a weekly radio show and newspaper column. His decision to televise the 17 Saturday night services of his 1957 New York crusade turned him into one of the most recognized and admired men in the country. Between crusades, Graham's friends and associates churned out a shelf full of books about the evangelist and his activities—often at Graham's urging, always with his approval. With the help of his staff, Graham himself published 24 books. These were often pegged to topics that were popular at the time, and some sold millions of copies. He spent plenty of well-photographed time with the rich and famous, appearing on talk shows, campus tours, and celebrity golf tournaments. Nearly every book about Graham has a figurative trophy case, stuffed with photos of Graham with presidents, world leaders, and the otherwise rich and famous.

What makes all this attention-seeking paradoxical is that there was not a whiff of vainglory in it. Graham was unfailingly modest about himself and lavish in praise of others. He always treated ordinary people and lowest-level staff workers with great respect and dignity. He never accepted honorariums for speaking engagements, and most of the millions of dollars he earned in book royalties he simply gave away. He always treated his antagonists with generosity and kindness. When the famous American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr published one of his many condescending attacks, Graham simply replied, “When Dr. Niebuhr makes his criticisms about me, I study them, for I have respect for them. I think he has helped me to apply Christianity to the social problems we face.” Time and again he would arrange meetings with his staunchest critics, and nearly every time his humility, transparency, and genuineness would melt their resistance. (Perhaps this explains why Niebuhr never would meet with Graham.)

Graham sincerely professed to dislike celebrity and to think nothing special of the company of the famous, but the reality was more complicated. As a young man in the first flush of fame, he pressed hard for an appointment with President Truman. In his late 70s, his claim in autobiography that he was reluctant to write about his famous acquaintances simply cannot be squared with the number of pages he spent doing just that. William Martin, Graham's best biographer, shows that ultimately fame was irresistible to Graham because it was so helpful in pointing people to Christ. Graham knew “that his message would reach more people, appear more legitimate, and have a greater impact if he were viewed as an important man.”

Reach more people he did. All over the world, Graham and his team set attendance records, from the 185,000 near London in 1954 to the 250,000 in New York City's Central Park in 1991 to the jaw-dropping 1.1 million–person crowd in Seoul in 1973. At the peak of his ministry, his newspaper column ran all over the country, Decision magazine topped out at some 4 million subscribers, and as late as 1987 his radio program aired on nearly 700 stations around the world. Graham's quarterly prime-time television shows have been seen all over the country for decades, attracting a much larger percentage of unchurched viewers than any other religious program.

Graham did more than evangelize. By the mid-1950s he shared the vision of Harold Ockenga, Carl F. H. Henry, and others for a new evangelicalism that would shed the skin of fundamentalist extremism. It would still be conservative at its theological core but would broaden beyond dispensationalism. It would take a softer line on evolution, engage mainstream scholarship, and take “a definite liberal approach to social problems.” Most importantly, it would deploy the parachurch to spread evangelical faith among mainline Protestants and then draw them into evangelical networks.

The first step was to establish and strengthen parachurch agencies that would take this approach. Graham was the key figure in founding Christianity Today magazine, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College, and the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability. Graham supported other key organizations like Fuller Seminary, the National Association of Evangelicals, and the National Religious Broadcasters. He encouraged numerous evangelical entrepreneurs to start their own ministries. Both Robert Schuller and James Robison began their weekly television broadcasts at Graham's instigation. Large donations from Graham himself helped launch Bill Bright's Campus Crusade for Christ and Vonette Bright's International Prayer Assembly. When Kenneth Taylor couldn't find a publisher for his Living Bible, the BGEA popularized it by distributing it to television viewers. It went on to sell 40 million copies. Most unusual of all, the BGEA regularly contributed large sums of money to other ministries like Young Life and Fellowship of Christian Athletes.

The second step was to engage the mainline Protestant world. Whereas the fundamentalists had shaken the dust off their feet as they left, Graham knew that there were many evangelical pastors and laypeople still in the mainline churches. Early on, he decided to hold crusades only where sponsored by the city's main organization of Protestant churches. The New York City crusade of 1957 was a watershed. Graham had declined earlier fundamentalist invitations to come to New York, but he accepted the invitation of the liberal Protestant Council of New York. While fundamentalists fumed that Graham was giving his blessing to liberalism, most Americans perceived that the elite of the mainline churches were giving their blessing to Graham. In one powerful symbolic move, Graham threw open the gates of the mainline churches to parachurch evangelicalism.

The result was heavy traffic in both directions, as evangelicals saturated the mainline with their message and a preponderance of Protestants relocated to districts outside the mainline walls. By the time Graham had finished his work, the old modernist dream of a non-supernatural Christianity was on life support, kept breathing only by the tenacity of mainline bureaucrats with their wistful memories of protest marches against segregation and the Vietnam War. In large measure, Moody's dream of a truly ecumenical evangelicalism had come to pass.

Abroad, Graham was even more influential in setting into motion events that brought together evangelicals from around the world and gave them a sense that they were part of a worldwide ecumenical movement. But before he could really devote himself to this work, he had to work through the most serious temptation that faced him in the first half of his career.

The Siren Song of Political Influence

Even before the Los Angeles breakthrough, Graham called together his inner circle of Beverly Shea, Grady Wilson, and Cliff Barrows and asked them to recall every stumbling block that had tripped up evangelists. They all came up with the same list—financial misdeeds, sexual immorality, inflated reports of success, and non-cooperation with local churches. Thereafter they put all team members on a straight salary, never met alone with women, used conservative attendance reports, and involved local churches both before and after crusades. Their commitment to these safeguards, shored up by regular prayer, produced an unsurpassed record of integrity.

None of them anticipated that the greatest danger would be the temptation to exercise political influence. In 1952 Graham secured an act of Congress permitting him to hold the first-ever religious meeting on the steps of the Capitol. Speaking in a voice that foreshadowed the New Christian Right of the 1980s, Graham announced that “the Christian people” of the country would likely vote as a bloc in the election of 1952. He said he would interview every presidential candidate and communicate his preference to other clergy. At the behest of his friend Sid Richardson, a wealthy and politically well-connected Texas oilman, Graham traveled to Europe to try to persuade Dwight Eisenhower to run as a Republican. Graham served as an unpaid religious consultant during the campaign, helping Ike add “a religious note to some of his campaign speeches.” He also publicly criticized Truman's State Department for its “many blunders” (an action he later regretted as “foolish and presumptuous”).

For the next two decades, Graham dipped in and out of politics. Presidents would brief him before trips abroad and debrief him on his return. They'd ask his advice about policy decisions, as when Eisenhower was considering sending troops to Arkansas to enforce school desegregation rulings. During the Johnson presidency, Graham—having concluded from a study of the Bible that Christians have a special obligation to the poor—aggressively lobbied Congress and did publicity on behalf of anti-poverty legislation. On celebratory occasions, like the 1964–65 New York World's Fair, Graham could seamlessly blend the story of Jesus and an appeal to come to Christ with a message about how America was founded on faith in God and the Bible.

What makes all of Graham's attention-seeking paradoxical is that there was not a whiff of vainglory in it.

Graham's critics insisted that his gospel of personal conversion neglected social reform, but Graham's record was better than they admitted. On civil rights, Graham was early to insist that racism and segregation were completely un-Christian. In 1952 he defied the governor of Mississippi and held racially mixed meetings. A year later—before the Supreme Court had overturned a single segregation law—he defied the Chattanooga crusade committee by personally taking down the cords that marked off the black seating section. In 1956, he wrote in Life magazine that racial prejudice was a sin, and before the New York crusade in 1957, he integrated his team by hiring Howard Jones as an associate evangelist. During the crusade he had Martin Luther King Jr. brief his team about his campaign for civil rights, and then King joined him on the platform for one of the meetings. Privately, King told Graham that his crusades were helpful in breaking down segregation. Certainly the segregationists saw it that way, swamping Graham with hate mail.

It was Graham's strong friendship with Richard Nixon that drew him into deep political water. In the 1960 presidential race against John Kennedy, Graham introduced Nixon to prominent ministers, coached him on how to appeal to Christian voters, and issued numerous barely veiled statements of support. As the election neared, Graham and his lieutenants organized a meeting that attacked the politics of Kennedy's Roman Catholic Church. However, Graham himself didn't attend the meeting, which provoked a furious backlash against its chair, Norman Vincent Peale. Liberal Protestants, Democratic politicians, Jewish groups, labor unions, and editorial pages—even pro-Nixon editors—issued scathing denunciations of anti-Catholic bigotry. Several newspapers and radio stations canceled Peale's column and his program, and several speaking invitations were withdrawn. By not discussing his role in the meeting, Graham ducked the backlash. Later, on the eve of the election, Graham was asked to write a pro-Nixon piece for Life. He did so, but at the very last minute withdrew it. In both cases, Graham walked up to the brink of throwing himself into partisan politics, only to withdraw at the last moment for fear it might hurt his ministry.

Graham also promoted Nixon in the 1968 race, and his victory brought Graham into the heart of politics. Graham did many favors for Nixon: supporting his Vietnam program, reporting on meetings with world leaders, co-hosting a God-and-Country extravaganza on Independence Day, and regularly arranging meetings with conservative clergy so the White House could explain its policies. Graham stayed in close contact with the White House during Nixon's re-election campaign and did it many favors, one of which was negotiating with Mark Hatfield to keep him from challenging Nixon for the nomination. Nixon, in return, did several favors Graham requested—making sure that evangelical parachurch workers got draft deferments, bringing a Christianity Today reporter on Nixon's momentous China visit, and, most importantly, meeting with a group of black ministers and solving some problems they were having with the Office of Economic Opportunity.

When the S.S. Nixon hit the Watergate iceberg, a good many of those around the president went down with the ship. Graham's initial public reaction was strong support for Nixon, but as damning evidence accumulated, Graham's statements modulated. Soon he was taking fire from Nixon's friends as well as his enemies, and he was probably glad that he was out of the country for most of the controversy. Graham's deep personal love for Nixon made the Watergate revelations extraordinarily painful—he wept, he threw up—for they revealed a facet of Nixon's character that Graham had never even glimpsed. Ruth later said that it was the most painful personal experience he had ever gone through.

Graham resolved never again to get so enmeshed in politics. When the New Christian Right began to organize, some of the biggest names in the evangelical parachurch—Bill Bright, Pat Robertson, and James Dobson—succumbed to the Falwellian temptation and began grasping for political power. Graham privately warned them not to go down that road. He'd been there, and it had nearly burned him. Besides, by this time he had caught a much grander vision—the challenge of building an international Christian movement that would be both evangelical and ecumenical.

Billy Graham, World Christian

Evangelicals at mid-century had a curiously divided mind. When preaching the universal gospel of sin and salvation to Americans, they had a compulsion to varnish it with the old Puritan idea of America as God's chosen nation, facing special judgment for its sins. They often talked as though the salvation of America was the object of conversion. Then the next week they'd pack their bags and head overseas, preaching a gospel stripped free of nationalistic themes.

So with Graham. He could preach America the Chosen with the best of them, but he also saw the entire world as his parish. Immediately after forming YFC, Torrey Johnson sent his best evangelists on a months-long tour of war-ravaged Europe. A year later, as leaders of the world's Protestant denominations were about to open the first meeting of the World Council of Churches in Geneva, Switzerland, YFC convened 400 delegates from 27 nations in a nearby Swiss town. Graham attended both meetings. He came away from the WCC meeting disappointed with its liberal theology, but thrilled with the vision of Protestants from around the world cooperating. The YFC gathering raised the question: Would it be possible for evangelicals working outside the denominational structure to build world-wide cooperative networks?

But another question came first: Would a Graham revival work outside of America? Beginning with the 1954 crusade in the London neighborhood of Harringay, the answer was a resounding yes. Twelve weeks of overflow crowds had the long-term effects of making the Anglican clergy more evangelical and making Graham an international figure. Contacts made there led to an astonishing series of mass meetings in India that produced far more inquirers than counselors were prepared for. These in turn led Graham's translator, Akbar Abdul-Haqq, to become an associate evangelist with the BGEA and begin a string of successful crusades in India. In 1959, crusades in Australia and New Zealand generated enormous stadium crowds and television audiences, and when Graham finally departed, his popularity there ranked second only to the Queen's.

For the next four decades, Graham traveled across every continent but Antarctica, almost always drawing well, and with exceptional success in Berlin, Brazil, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, Mexico City, Finland, and Canada. But nobody had ever seen anything like what happened in South Korea in 1973. With Baptist pastor Kim Jang Whan (“Billy Kim”) doing an inspired job of translating, Graham spoke in person to 3 million during the main crusade, with another million and a half attending associate crusades in other cities and millions more watching on television. Inquirers numbered 100,000; they accelerated membership growth that was already spiraling upward. Graham's visit did much to bridge divisions between different groups of Korean Christians and give them a vision for evangelizing all of Korea. Soon Korean evangelists themselves were drawing crowds every bit as large as Graham's, and Korean churches were sending out more missionaries than any nation except the United States.

When the New Christian Right began to organize, Graham privately warned them not to go down that road. He'd been there, and it had nearly burned him. Besides, by this time he had caught a much grander vision.

Traveling the world helped convince Graham that an evangelist has a broader set of responsibilities than merely preaching. In 1972 he visited Northern Ireland in a noteworthy attempt to reduce hostilities there. The next year he visited South Africa when the apartheid government finally agreed to his long-standing demand that all meetings be completely integrated. The 100,000 in Durban and Johannesburg who heard the evangelist declare that apartheid was doomed were the largest interracial gatherings the nation had ever seen. A famine in nearby West Africa led the BGEA to adopt disaster relief as a permanent part of its mission, and the pre-crusade prayer meetings spawned an interracial women's prayer movement that had 350,000 members within five years.

Traveling the world also damped down Graham's youthful anti-communism. His dream of preaching behind the Iron Curtain finally came to pass through the unlikely intervention of Hungarian émigré physician Alexander Haraszti. For five years Haraszti pushed and pulled his contacts in Hungary, and at the last minute Graham pulled some strings in the Carter White House. The 1977 visit was seen as a success by everyone concerned—Graham, the Hungarian government, leaders of the Catholic, Reformed, and Free Churches, and even Jewish leaders. Haraszti parlayed this success into an invitation to visit heavily Roman Catholic Poland the next year, a successful tour that also smoothed interfaith relations there. As early as 1963 Graham had spoken out against the nuclear arms race, but on this trip, a visit to Auschwitz affected him so deeply that he began to make world peace a frequent theme in public talks.

This, in turn, opened the door to the Soviet Union, which after much negotiation invited Graham to attend a pro-Soviet peace conference in 1982. After an initial go-ahead from the Reagan White House, Graham indicated he would accept the invitation, only to come under strong pressure from the State Department, other evangelicals, and his own organization to decline it. He went anyway, but at times must have wondered at the wisdom of his decision.

The visit itself went awkwardly at several points, and afterward Graham was portrayed by the Western press as a naïve dupe of the Soviets. But the Soviet government came away from Graham's visit with new respect for his diplomatic skills, and this opened the door to visits to East Germany and Czechoslovakia. After that came a very successful 1984 preaching tour of the USSR, and then a remarkable visit to repressive Romania, where over 150,000 people poured into the streets. Graham used every trip to arrange private visits with government officials, which he used both to present the gospel and to press them to ease religious restrictions in their countries. His team also used these visits to strengthen the churches and ease tensions between them.

The extent of Graham's influence is impossible to measure, but it is a fact that in the 1980s religious restrictions behind the Iron Curtain eased while the churches grew stronger. This put them in position to shelter and nurture the pro-democracy movements that helped bring down the Communist regimes. There's no doubt that those regimes thought they could exploit Graham to bolster their image. But Graham may have been right in the long run when he predicted, “My propaganda is stronger than theirs.”

When negotiating terms of the evangelist's visit to the Soviet Union, Alexander Haraszti once declared that Billy Graham “is the head of all Christianity. He actually is the head of the Roman Catholics, the Orthodox, the Protestants—everybody—in a spiritual way … because he is above these religious strifes.” A fit of diplomatic hyperbole, to be sure, but in it was a mustard seed of truth. By the 1970s, Graham possessed tremendous international prestige, and his institutional location in an independent parachurch organization made it easy for him to work with Christians from all denominations.

His first attempt to pull together a worldwide evangelical movement was the 1966 Berlin Congress on Evangelism, which he hoped would pull together an ecumenical movement along lines envisioned by Dwight Moody. While a WCC conference in Switzerland was attacking Billy Graham, comparing evangelicals to Nazis, and calling for world-wide revolution, Carl F. H. Henry led the 1,200 Berlin delegates—only 200 from the US—in a 10-day effort to work out a global theology of evangelism.

One outcome of Berlin was the founding of Fuller Seminary's School of World Mission. But more than anything else, Berlin taught Graham's people that many WCC member churches in Asia, Africa, and Latin America also had an intense concern for evangelism. So in the years following, the BGEA organized and financed conferences in those regions, as well as in Europe and North America, making sure that each conference had leadership drawn from its region. The success of these conferences led Graham to begin planning for a major international conference to work out worldwide strategies for evangelization.

That planning bore fruit in 1974, when some 2,400 evangelicals—half from outside Europe and North America, more than half under age 45—gathered in Lausanne, Switzerland. Lausanne gave a tremendous boost to evangelical foreign missions. Delegates learned from Fuller Seminary's Donald McGavran and Ralph Winter that nearly 2 billion of the world's people were unreached by the gospel. Since they had no form of indigenous Christianity in their midst, renewed efforts at cross-cultural missionary work were absolutely essential. The Lausanne Covenant committed evangelicals to this task, as well as to working for “justice and reconciliation throughout human society and for the liberation of men from every kind of oppression.” The BGEA agreed to fund an ongoing Lausanne Committee, which in turn spawned regional meetings. The result was unprecedented contact and collaboration between evangelicals across national and denominational lines, especially in the non-Western world.

Despite this quantum leap forward in global evangelical cooperation, Graham wasn't finished. The group really on his heart was those who shared his calling as itinerant evangelists. So in 1983 the BGEA brought nearly 4,000 of them to Amsterdam for nine days, almost entirely at its own expense. They came from 133 nations, 70 percent from non-Western ones. Only 40 percent had any formal training, and only 10 percent had ever before attended a conference. Plenary sessions and some 200 workshops focused on the priority of proclaiming the gospel, and on practical strategies—how to gather a crowd, keep their attention, preach a message in a few minutes, and get local churches to help with preparation and follow-up. The conference was so well-received that Graham's organization immediately started preparing a sequel in 1986, which drew over 8,000 attendees from 173 nations. The BGEA picked up the $21 million tab without approaching any foundations or wealthy donors.

The Amsterdam conferences gave the BGEA a contact list of 12,000 evangelists all over the world, which it then tapped to organize a series of satellite crusades between 1989 and 1995. The first three targeted Africa, Asia, and Latin America, respectively; the final two reached 1,400 and 3,000 locations around the world—the latter requiring translation into 117 different languages. And still there were evangelists from all over the world who pleaded for a reprise of the Amsterdam conferences. So in 2000 the BGEA, again at its own expense, brought 10,700 conferees from 209 countries. Graham himself was not healthy enough to attend, and though the delegates wanted to see him, his absence probably had little effect on the impact of the conference.

Evangelical Ecumenism

Amsterdam and the satellite crusades may have been Billy Graham's finest moments. Many of the characteristic elements of his early years were absent—calls to save America, striving to make evangelicalism respectable, hobnobbing with celebrities, audiences of the middle class. Amsterdam was evangelism purified. Graham and his organization poured themselves out for the entire world, encouraging and empowering men and women, great and small, who shared Graham's burden to preach the gospel of Jesus Christ.

William Martin observed that the forces gathered and unleashed at the Berlin, Lausanne, and Amsterdam meetings constitute a third worldwide ecumenical movement, every bit as important as the World Council of Churches and the Roman Catholic Church. The amazing thing about the evangelical movement is that it is sustained not by a single organizational entity, but by multiple parachurch organizations, independent of each other but dreaming a common dream. Graham's genius was his ability to inspire people not to follow him, but to strike out on their own, following Jesus by proclaiming the gospel in their own way; and then to call them together, to inspire and equip thousands more to do the same thing. We may never see his like again. But perhaps—because of his faithfulness in calling, equipping, and sending others to stand up and proclaim, “The Bible says…”—the world won't need another Billy Graham. And he and Moody, whom Graham was sure he'd meet in heaven, can stand together and look on in wonder at what God hath wrought.

Michael S. Hamilton, vice president for programs and special initiatives at the Issachar Fund, is currently working on the book Calvin College and the Revival of Christian Learning in America (Eerdmans, forthcoming).

1