Those late-night board meetings at church may have you dragging the next day, but they’re actually a sign of a healthy church.

Boards that meet for longer than two hours reported that their leadership was more effective than those that meet for a shorter period of time, according to a new survey by the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA).

For the first time, ECFA asked board members and church staff from more than 500 churches how their congregations are governed. Here’s a snapshot:

- Church boards are known by more than 70 names, including the popular Board of Elders (37%), Board of Directors (13%), and Board of Trustees (7%).

- The median church has eight board members, and about half have members who are related to each other or to church staff (48%).

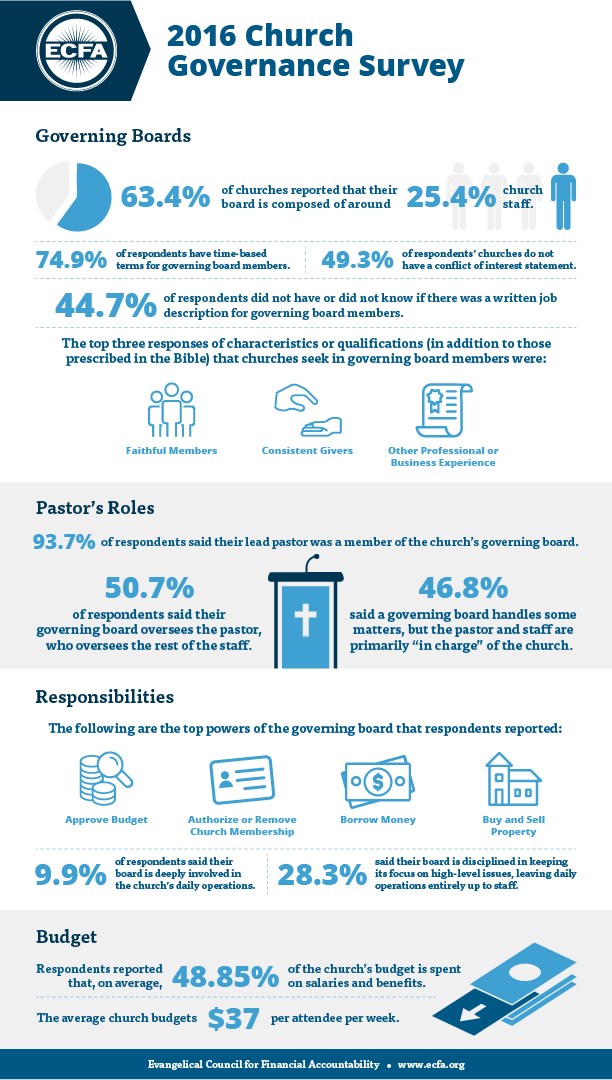

- Nearly 80 percent of boards include at least one staff member. For almost two-thirds of church boards (63%), church staff make up a quarter of the members.

- Almost all boards (94%) include the pastor, who doesn’t get a vote on 30 percent of boards, is allowed to vote on 43 percent of boards, and chairs (and votes on) 21 percent of boards.

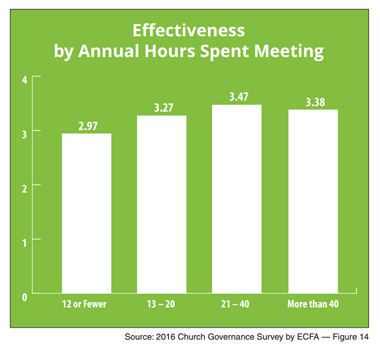

“The most effective boards spend between 21 and 40 hours together over the course of a year,” ECFA reported.

That adds up to at least one two-hour meeting a month. Boards that meet less frequently self-report being less effective.

It’s a good thing, then, that nearly 60 percent of church boards already do meet monthly. The median meeting had 90 percent of members normally present; for 20 percent of churches, 100 percent of board members were usually there.

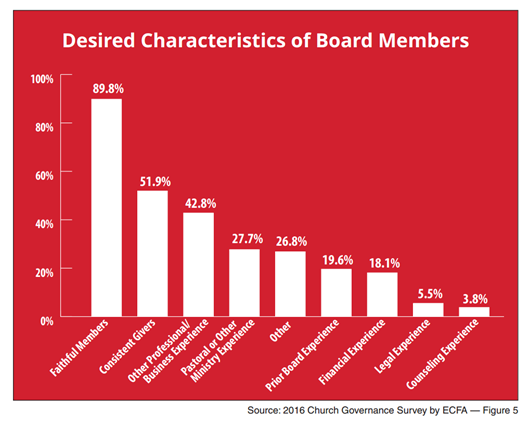

That’s probably because the No. 1 qualification for a board member is faithfulness. Almost 90 percent of those surveyed said that was a characteristic they desired in church board members, far above the No. 2 qualification—being a consistent giver—which was desired by 52 percent of respondents.

Having professional or business experience (43%) is also a plus, but boards don’t seem to be looking for financial experience (18%) or legal experience (5.5%). The only thing less popular: having counseling experience (4%).

Church board members are generally elected, usually by the congregation after being nominated by a committee (34%) or board (20%). Very rarely does a pastor appoint the board members alone (5%); even more rarely does the congregation elect them without a nomination process (4%).

Three-quarters of church boards have term limits, usually ranging from one to five years. But “the impact of term limits is limited” because 45 percent of churches “don’t limit the number of terms a governing board member may serve,” ECFA reported. While 18 percent of churches require at least a year off between terms, 67 percent of churches allow back-to-back terms without time off, and 12 percent allow three terms without a mandatory break.

Most church boards function pretty well; at least, 81 percent of those surveyed said their board was “very effective.”

ECFA identified six top characteristics that seemed to point to a healthy board:

- Board members were chosen by someone other than the lead pastor.

- Policies were in place—and the board had the ability—to ask an underperforming staff member to resign.

- The board was able to challenge and correct a lead pastor when necessary.

- An active strategic planning process was in place.

- Time and energy were devoted to assessing risks and opportunities.

- The board guided the staff with strategic—but not tactical—input.

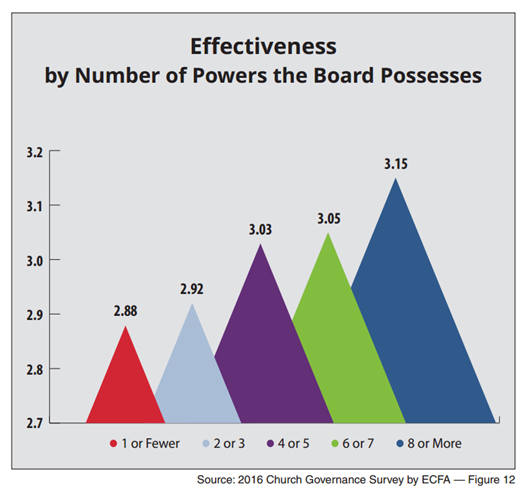

The board was also more effective if it had more power. Church leaders reported a split on whether board members (50.7%) or the pastor and church staff (46.8%) were actually running the church. Those who reported that the board was in charge rated its leadership slightly more effective than those who reported that their pastor and staff were in charge.

One factor did make a big difference in the perception of power. In churches where the founding pastor still serves, 59 percent said the pastor and staff were in charge instead of the board. But in churches where the founding pastor is no longer there, 57 percent said the board is primarily in charge.

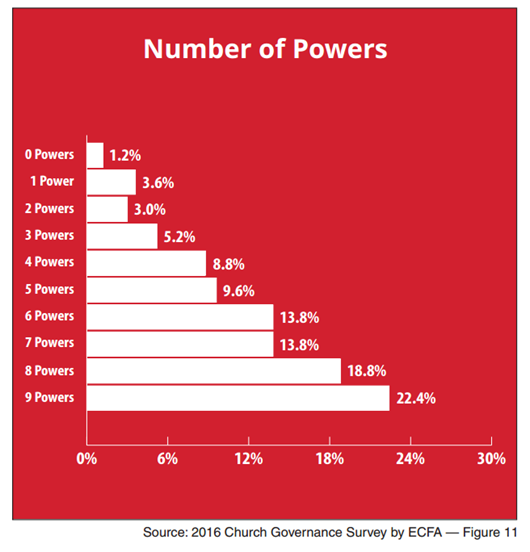

Not surprisingly, boards with less power to make decisions—from borrowing money to terminating the pastor to selecting other board members—are seen as less effective than those with more power.

Boards reported that their greatest strengths were setting the pastor’s compensation (3.53 on a 4-point scale) and holding the pastor accountable (3.42). They ranked themselves lower on offering strategic input (3.07), challenging or correcting the pastor (3.01), and assessing risks (2.98).

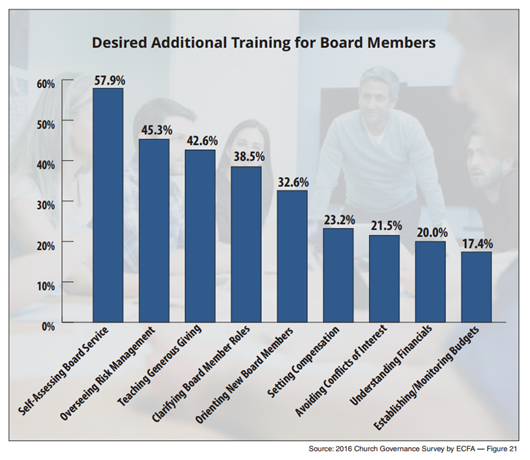

Most survey respondants said they’d like training on self-assessing their board service, overseeing risk management, and teaching generous giving. They were less interested in avoiding conflicts of interest (only 16 percent of churches have a policy and check conflicts annually), understanding financials, and establishing budgets.

ECFA is offering a webinar today on the survey findings.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month