Last night in his speech accepting the Republican party nomination for president, Donald Trump again called for a repeal of Lyndon B. Johnson’s ban on tax-exempt groups endorsing political candidates.

“At this moment, I would like to thank the evangelical community, who have been so good to me and so supportive,” Trump said. He went on:

They have so much to contribute to our politics, yet our laws prevent you from speaking your minds from your own pulpits. An amendment, pushed by Lyndon Johnson many years ago, threatens religious institutions with a loss of their tax-exempt status if they openly advocate their political views. I am going to work very hard to repeal that language and protect free speech for all Americans.

In an unusual move, Politifact rated Trump’s claim as true.

Trump first announced his intention to repeal the amendment in February, and reiterated it to about 1,000 evangelical leaders last month.

“I think maybe that will be my greatest contribution to Christianity—and other religions—is to allow you, when you talk religious liberty, to go and speak openly, and if you like somebody or want somebody to represent you, you should have the right to do it,” said Trump at the event. “People walking down the street have more power than you, because they can say whatever they want.”

Repealing the amendment figured prominently in Trump’s platform meetings, Time magazine reports.

“They understand the importance of religious organizations and nonprofits, but religious organizations in particular, which is what the Johnson Amendment affects, to have the ability to speak freely, and that they should not live in fear of the IRS,” Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council and a member of the GOP platform committee, told Time.

Liberty University president Jerry Falwell Jr., one of Trump’s earliest evangelical supporters, called the repeal “almost as important for Christians as the appointment of Supreme Court justices.”

But until last week, the issue hasn’t seen much discussion. While 70 percent of white evangelical voters told the Pew Research Center last month that Supreme Court appointments were “very important” in deciding who to vote for, the Johnson Amendment wasn’t even on the list. (The issues white evangelicals are most concerned about: terrorism, the economy, and foreign policy/immigration.)

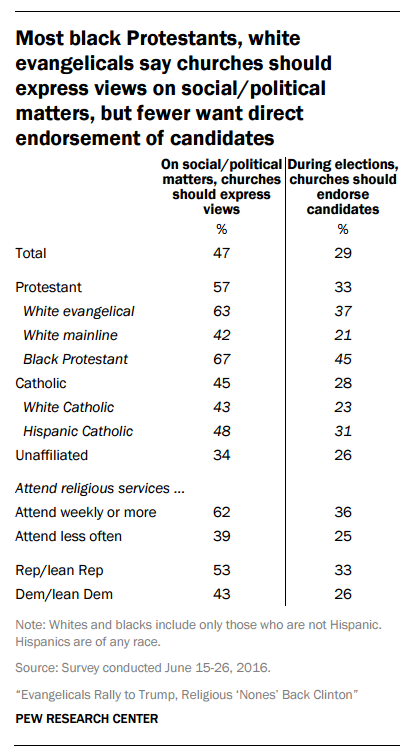

In fact, only about one-third of white evangelicals (37%) and about half of black Protestants (45%) believe that churches should endorse candidates during elections. Overall, Americans aren't in favor of churches officially supporting one candidate, though the number has risen slightly over time.

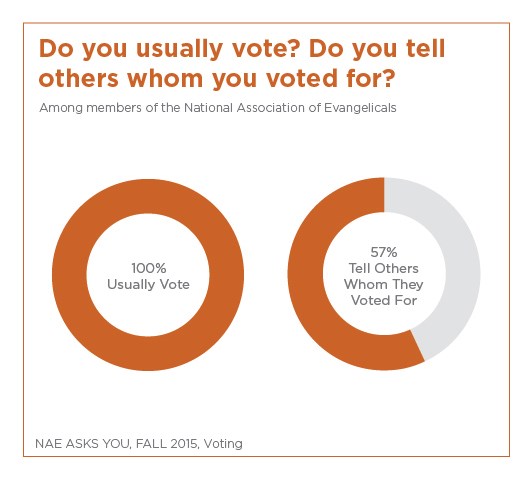

Most evangelical leaders seem to agree. A 2015 National Association of Evangelicals survey found that 43 percent of its members don’t tell anyone whom they voted for. While most (57%) do tell, some said they just told family or close friends, or told only when asked.

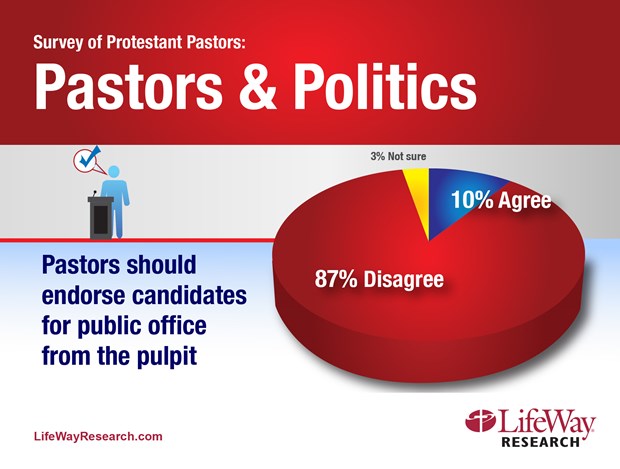

LifeWay Research found in 2012 that 9 in 10 Protestant pastors believe that the government shouldn't prohibit pastors from preaching politics, but that 9 in 10 also believe pastors shouldn’t do it.

And they aren’t. In fact, fewer pastors are involved in politics in 2016 than during the mid-term elections in 2014, according to a June survey of 600 theologically conservative Protestant pastors by Barna Group for the American Culture & Faith Institute.

The decline in political activity proved true for every category:

- Sponsor a voter registration process at your church: 12% did so in 2016, down from 21% in 2014

- Actively encourage people to vote: 7% did so in 2016, down from 9% in 2014

- Invite candidates to speak to your congregation before the election: 3% did so in 2016, down from 5% in 2014

- Preach at least one sermon about a public policy issue: 1% did so in 2016, down from 37% in 2014

- Distribute voter guides to your congregation: 36% did so in 2016, down from 45% in 2014

- Include election-related information on your church’s website: 4% did so in 2016, down from 5% in 2014

- Encourage church members to get actively involved in a campaign: 20% did so in 2016, down from 29% in 2014

- Speak to your congregation about the importance of voting: 62% did so in 2016, down from 78% in 2014

There are some exceptions. Before his termination, megachurch pastor Perry Noble shared on Twitter that he would not be voting for Trump in the primaries and encouraged his followers to vote for someone else also. Falwell Jr. endorsed Trump early on, while his brother, megachurch pastor Jonathan Falwell, said he would not.

“As a pastor of a local church attended by people of different political parties and persuasions, I have made it my practice not to endorse political candidates,” wrote Jonathan Falwell. “I do not believe it is my responsibility to point people to a candidate but rather to point people to Jesus Christ as the ultimate and only hope for mankind and the problems we face as a nation.”

The Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF) has been at the forefront of the fight against the Johnson Amendment, initiating the annual Pulpit Freedom Sunday in 2008 in open defiance of the law. Since then, 2,032 pastors have violated the amendment, according to ADF.

There have been attempts to shut the initiative down, including a 2012 request by Americans United for the Separation of Church and State that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) investigate Robert Jeffress, senior pastor of First Baptist Church of Dallas, after he endorsed presidential candidate Rick Perry.

But the IRS has been slow to respond with legal action. Several years ago, it was stalled on the question of who had the authority to authorize church audits. In 2014, it finally agreed to investigate after the Freedom From Religion Foundation sued over the matter. But by then, the IRS was under a moratorium related to the agency’s controversial scrutiny of Tea Party organizations.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month