Since the 1950s, the IRS has banned preachers from endorsing candidates during church services. Donald Trump has pledged to eliminate the ban, calling it his “greatest contribution to Christianity” if he is elected president.

However, most Americans—including evangelicals—seem to like the status quo.

Four out of five Americans say it is inappropriate for pastors to endorse a candidate in church, according to a newly released report from LifeWay Research. Three-quarters say churches should steer clear of endorsements.

For the most part, Americans with evangelical beliefs agree that pastors and churches should abstain from using their resources—including the pulpit—to campaign for a particular candidate. Seventy-three percent say pastors should abstain, while about 65 percent say churches should abstain.

“Americans already argue about politics enough outside the church,” said LifeWay executive director Scott McConnell. “They don’t want pastors bringing those arguments into worship.”

Yet fewer than half of Americans—and just 33 percent of evangelicals—want churches to be punished if they do endorse candidates.

The ban on endorsements, known as the Johnson Amendment, dates back to a conflict between then–US Senator Lyndon Johnson and a Texas nonprofit, which opposed his re-election bid. Approved in 1954, the IRS rule bans all 501(c)(3) nonprofits, including churches, from active involvement in political campaigns.

Since 2008, a group of mostly Protestant pastors has challenged the ban each year by endorsing candidates in an event called Pulpit Freedom Sunday. Recent polling shows few churchgoers have heard their pastor endorse a candidate.

[Editor’s note: Trump, who helped make repealing the Johnson Amendment a plank in the GOP platform, has received fewer sermon endorsements than rival Hillary Clinton, according to the Pew Research Center. While some atheists have pushed for the punishment of pastors who participate in Pulpit Freedom Sunday, support for the freedom of pastors to publicly endorse candidates is on the rise—even among religious nones.]

The new LifeWay report, which compares results from surveys of 1,000 Americans in 2008 and 2015, found that disapproval of endorsements, while a little lower, remains high overall.

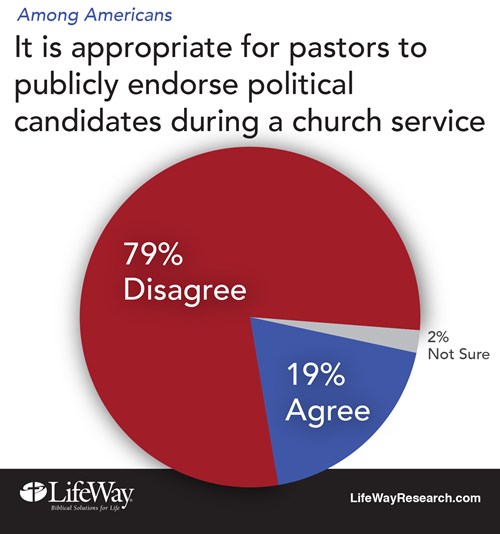

In both surveys, LifeWay asked Americans to respond to the following statement: “I believe it is appropriate for pastors to publicly endorse candidates for public office during a church service.”

In 2008, 86 percent of Americans disagreed, a number that dropped to 79 percent in 2015. The 13 percent that agreed with the statement in 2008 grew to 19 percent in 2015.

Support for endorsements, while tepid across denominational lines, was stronger among Protestants (20% agreed) than Catholics (13%). Those with evangelical beliefs (25%) were more likely to agree than other Americans (16%).

[Editor’s note: This summer, Pew found that a minority of white evangelicals (37%) and black Protestants (45%) want pastors to endorse candidates during elections. Among pastors themselves, Lifeway found in 2012 that 9 in 10 Protestant pastors believe that the government shouldn't prohibit pastors from preaching politics, but that 9 in 10 also believe pastors shouldn’t do it.]

But while approval for pulpit endorsements has grown, approval for personal endorsements has dropped. In 2008, about half of Americans (53%) said it was appropriate for pastors to endorse candidates outside of their role at church. In 2015, that dropped to 43 percent.

Americans also want churches to steer clear of endorsements and campaign involvement. Both in 2008 and 2015, about three-quarters disagreed that “it is appropriate for churches to publicly endorse candidates for public office.”

Even more (85% in 2008, 81% in 2015) said it was not appropriate “for churches to use their resources to campaign for candidates for public office.”

Three in 10 of those with evangelical beliefs (29%) said endorsements by churches are appropriate, more than those without evangelical beliefs (21%). Protestants were more likely (27%) to approve of endorsements than Catholics (18%), and those who attend church once a week or more (29%) were more likely to approve of endorsements than those who rarely or never attend (18%).

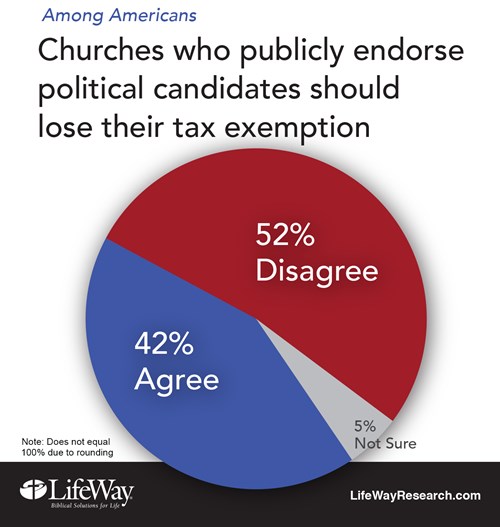

But while Americans don’t want their pastors or churches endorsing candidates or getting involved in campaigns, neither do they think churches should be punished if they do.

In 2008, more than half of Americans (52%) said churches should lose their tax exemption for publicly endorsing candidates. That number dropped to 42 percent in 2015.

Still, there are some demographic differences.

Men (47%), those who live in the Northeast (46%), and those who live in the West (48%) were more likely to say that churches should lose their tax exemption. Women (38%) and Southerners (37%) were less likely to approve of the punishment.

Those from non-Christian religions (56%), religious nones (53%), and those who rarely or never go to church (52%) were more likely to agree that churches should lose their tax exemptions.

Christians (37%), those with evangelical beliefs (33%), and those who go to church at least once or twice monthly (35%) were less likely to agree.

“Endorsements from the pulpit are unpopular and most Americans say they are inappropriate,” McConnell said. “But they don’t want churches to be punished for something a pastor said.”

Methodology:

The phone survey of Americans was conducted Sept. 14–28, 2015. The calling utilized Random Digit Dialing. Fifty percent of completes were among landlines and 50 percent among cell phones. Maximum quotas and slight weights were used for gender, region, age, ethnicity, and education to more accurately reflect the population. The completed sample is 1,000 surveys. The sample provides 95 percent confidence that the sampling error does not exceed plus or minus 3.6 percent. Margins of error are higher in sub-groups. Comparisons are also made to a LifeWay Research telephone survey of Americans June 12–14, 2008, using randomly dialed listed landlines.

LifeWay Research is a Nashville-based, evangelical research firm that specializes in surveys about faith in culture and matters that affect churches.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month