Memorial Day weekend seemed like a grand time for camping with friends in North Carolina, and it was, right up until a downpour began Sunday night.

According to plastic cups left out on the picnic tables - the storm hit after dark, leaving precious little time for securing items beneath tent canopies - a good two inches of rain fell in about as many hours, and additional sprinkles every half hour or so ensured that nothing had a chance to dry out. Two tents in our group were flooded out, though luckily not ours. My 3-year-old daughter managed to sleep through the whole thing.

Church historian that I am, as I lay awake, listening to heavy drops pelt the rain fly, I thought, This must have happened a lot at 19th-century camp meetings. I wonder how they handled it?

Upon returning to the electrified world, I ran some Web searches to find out.

Organizers at Cane Ridge in Kentucky, site of an iconic 1801 revival that ignited the Second Great Awakening in the heartland, dodged bad weather by erecting a shed "sufficiently large to protect 5,000 people from wind and rain, [covered] with boards or shingles." (That description appears in the autobiography of Peter Cartwright, camp meeting preacher extraordinaire, who was himself converted at Cane Ridge.) Organizers of a Prohibitionist rally in New York in the 1880s, though, were not so fortunate.

An unnamed reporter for The New York Times had great fun writing dispatches from a waterlogged teetotalers' rally at Sing Sing in August 1887. "However much the prohibitionist may delight in water," began the August 23 report, "there was nobody present at the Sing Sing camp meeting yesterday who would not admit that it was possible to have too much of a good thing."

Prohibitionists, of course, advocated water as a beverage, not as precipitation. They were able to promote water as a healthy alternative to liquor thanks to advances in sanitation. Until the latter half of the 19th century, it simply was not safe to drink water in much of Europe and North America (nor aboard ships - the Mayflower landed where it did because the Puritans had run out of beer). Filtration, sewer systems, and other developments finally made it possible to eschew fermentation.

The 1887 rally aimed to generate support for both Prohibition legislation and the Prohibition Party, which had been founded in 1869. Rain diminished the crowd to 300 or 400, but, the paper reported, "what the meeting lacked in numbers they made up in enthusiasm." Sheltered by a tabernacle, attendees heard speeches from such celebrities as Presbyterian theologian Dr. Herrick Johnson, formerly of Auburn Theological Seminary but by that time teaching in Chicago; Rev. E.J. Hill (famous on Google for being a Son of the American Revolution and for discovering Hill's Pondweed); Dr. Howard Crosby, pastor of Fourth Avenue (now Broadway) Presbyterian Church and Chancellor of New York University; and the Hon. John P. St. John, former governor of Kansas. The Times called the array of speakers "prodigal in quantity and quality." Given the nature of their cause, one assumes the speakers were anything but prodigal in their personal habits.

One of the addresses received particular attention in the news report. In a "long and elaborate speech," Dr. Johnson took on ten fallacies about the Prohibition Party, the first being that prohibition presented "an unwarrantable invasion of natural rights beyond the proper domain of legislation." Johnson granted that personal liberty was wonderful, unless the exercise of this liberty hurt someone else.The paper cited as one of Johnson's examples, "A man exercising his personal liberty by taking a hen off a roost would not be doing wrong unless he took some other person's hen." (Why anyone would be tempted to saunter up and remove a hen from a roost is beyond me.)

In an eerie continuation of this logic, Johnson again made news in 1894 when he told reporters, in reference to the Pullman Strike, "There is but one way to deal with these troubles now and that is by violence. … There must be some shooting, men must be killed, and then there will be an end to this defiance of law and destruction of property." Both unlimited exercise of personal liberty and the abrogation of liberty can be dangerous things.

The second fallacy Johnson addressed was more explicitly theological: the objection that, because Jesus drank wine, Prohibition reflected badly on him. Johnson's example again revealed his historical moment. He argued that frame buildings had been constructed since the Savior's day, but in some cases, frame buildings posed a public hazard. To outlaw frame buildings, then, was just sound policy, not an aspersion cast on the blessed carpenter. For one thing, Johnson's knowledge of ancient architecture seems a bit shaky. Any child brought up with modern Bible picture books knows that Bethlehem did not have wooden row houses. For another thing, the outlawing of frame houses stemmed from 19th-century fears of urban fires, such as the one that gutted Chicago in 1871. Today's public safety concerns are rather more complicated.

It was difficult to tell how the Times reporter evaluated these goings-on. He (or she) made plenty of little jokes about the soggy water-drinkers, but he also sat through many speeches and seemed to have represented both their content and their passion faithfully. In the end, he at least admired the activists' dedication. A follow-up report dated August 25 began,

Any assemblage other than the enthusiastic Prohibitionists now holding a camp meeting at Sing Sing would have become discouraged yesterday with the reverses they have had in the way of weather. Yesterday again leaden skies and a cold and exceedingly wet rain compelled the retirement of the hammock and the substitution of rubbers for tennis shoes and red worsted slippers. But the cold-water army did not droop. Some of them even found comfort in the reflection that the liquor dealers on parade in this city would have to put up with a copious dosing of the element they have tried to make unpopular as a beverage. "The rain falls alike upon the just and the unjust" was, in their opinion, proved yesterday, and they were not the unjust either.

Misguided though they might have been, those dogged Prohibitionists deserve a measure of respect.

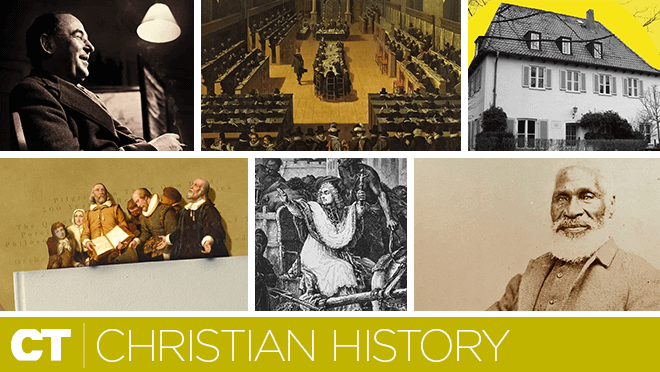

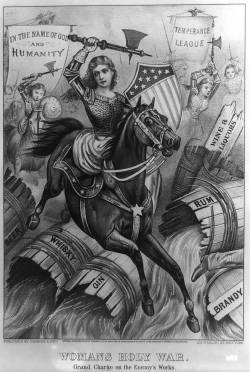

Image: Allegorical cartoon from 1874: Women's Holy War: Grand Charge on the Enemy's Works, courtesy Library of Congress via Wikimedia Commons.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month