I grew up in a church that frowned on creeds, so it was as a musician that I learned the Nicene Creed. And I learned it in the fractured, phrase by phrase way it appears in the great concert masses, with several minutes of music devoted to each segment.

I can still remember the first time I heard the creed sung as part of Bach's magnificent Mass in B-Minor. It was nearly 40 years ago at UCLA under the baton of Roger Wagner. The pain of Bach's descending line in the Crucifixus (He was crucified) nearly moved me to tears, and then I wept with joy at the giddy shock of the brilliantly ascending Et Resurrexit (And rose again).

Bach knew how to make theology sing. And the Nicene Creed still sings for me.

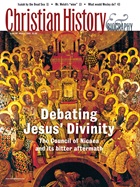

This issue of Christian History & Biography is about things eternal and things that change. At the Council of Nicaea the church affirmed the eternal equality of God the Son with God the Father. But at that same council, the church found itself coping with a brand new situation.

From the beginning, the church wanted to be in universal agreement on its teachings. The New Testament is, in part, the story of the church sorting out divisive issues.

But with the legalization of Christianity after Constantine's vision, the unity of the church took on political significance. Constantine expected the church to be a force for unity rather than division. Shortly after he issued the Edict of Milan (A.D. 313), which extended religious freedom to Christians, he became embroiled in a long and messy controversy between rival church factions in North Africa. When the Roman bishop failed to solve the problem, Constantine became angry and intervened.

By 325, when the Council of Nicaea met, the bishops had only had a dozen years in which to work out their relationship with the Emperor. Constantine had given Christianity preferential treatment, but his rival Licinius had reneged on an earlier agreement and began persecuting Christians once again. Constantine finally beat Licinius into submission and secured full freedom for Christians only a year before the council met.

Thus the situation was fresh, and the majority of Christians were deeply indebted to Constantine for their freedom. And it is in this context of change that we read about the efforts of the bishops at Nicaea to discover doctrinal unity.

In a recent newsletter, Martin Marty quoted the title of H. M. Kuitert's book, Everything Is Politics but Politics Is Not Everything. That sentence could have been written about Nicaea. And knowing how to sort out the politics of Nicaea is tricky. Everyone writing in this issue affirms the doctrinal decisions of Nicaea, but given the limited sources and the chronological and cultural distance, they will naturally view these events through different windows.

We are indebted to D. H. Williams, professor of historical theology at Baylor University in Waco, TX, for lending us his expertise during the planning and shaping of this issue.

Change is also afoot at Christian History & Biography, as with this issue we welcome associate editor Jennifer Trafton and say goodbye to managing editor Chris Armstrong.

As issue 85 goes to press, Chris is in his first month of teaching at Bethel Seminary in St. Paul, Minnesota, having just joined the faculty as associate professor of church history. Chris has seen the magazine through an interesting evolution, broadening the scope of each issue while retaining our fundamental strength as a theme magazine. We're grateful to Chris for his excellent work. Chris is a man of many gifts—editorial, entrepreneurial, and educational—and we wish him the best as he begins a new life chapter at Bethel.

Chris did most of the planning for issue 85, but Jennifer Trafton has had the task of pulling together its various strands and working with the authors to shoehorn their contributions into the space available.

Jennifer and Chris have much in common, since they both earned degrees at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary and both studied under Grant Wacker at Duke University. While at Duke, Jennifer and Chris participated in two small groups together: one that read the writings of the Inklings, and another that discussed issues of faith and learning. (This magazine's Duke connection goes further: Former managing editor Elesha Coffman is currently engaged in graduate study there.)

Jennifer adds to her passion for church history an interest in literature, art history, and the Christian imagination. Her thesis at Gordon-Conwell dealt with George MacDonald's theology of the atonement. And she'll be bringing that knowledge to bear in assembling issue 86. MacDonald, the writer who influenced C. S. Lewis more than any other, typifies the Victorians' struggle for faith and sheds light on movements and thinkers that still shape us.

Copyright © 2005 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History & Biography magazine.

Click here for reprint information on Christian History & Biography.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month