It is impossible not to like Robert Ingersoll (1833-1899), the greatest champion of atheism in 19th-century America (indeed, perhaps in the whole of American history). Susan Jacoby, his most recent biographer, values highly his forthright attacks on orthodox doctrine, but fair-minded Christians have always been apt to admire him as well. His love of life was infectious; his wit was delicious. Colonel "Bob" Ingersoll was a generous, large-hearted man, filled with compassion for those who were suffering or oppressed.

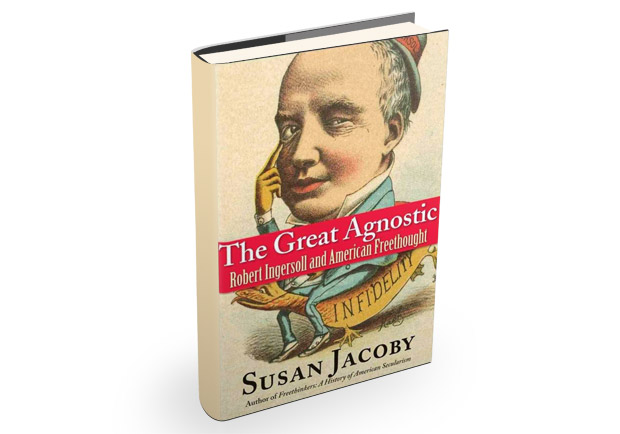

It is right and fitting that, in The Great Agnostic: Robert Ingersoll and American Freethought (Yale University Press), Jacoby would want to celebrate such a life and thereby introduce a new generation of readers to her hero. She does this as a proud member of the atheist community in America.

Christian historical writing has now matured to the point where it has dispensed with hagiography. Christian scholars are convinced that we have as much to learn from the weaknesses and blind spots of our saints as we do from their strengths and achievements. The fledgling American atheist community, however, has not yet progressed this far. Jacoby therefore feels a need to airbrush her portrait into an inaccurate and unnatural perfection. This is all rather endearing: love covers a multitude of sins.

She imagines Ingersoll to be a great lover of learning, a formidable champion of education, and a model dispenser of knowledge to the masses. In truth, he was a superficial student and thinker. The historian Eric Brandt did a study of what sources Ingersoll was drawing on when he would evoke bodies of knowledge, and what he found was that this material was generally obtained secondhand from popular summaries. Instead of reading the historical, philosophical, or scientific work itself he had raided someone else's condensed account of it. Ingersoll even boasted, "I don't read more than three lines on a page of any damn book." "The Great Agnostic" knew he was out of his depth in a learned exchange of ideas and therefore steadfastly refused to debate anyone.

In his rhetorically powerful, highly entertaining public lectures, Ingersoll (a trained lawyer) would ask question after question in order to sow doubt in people's minds about their religious beliefs—a lawyerly technique that saved him the trouble of actually trying to prove any alternative views true. His most celebrated court case involved the Star Route scandal, a national sensation of public corruption. Ingersoll managed to get his clients acquitted even though everyone (including Jacoby) agrees that there is no doubt that the bribery took place. This should be a clue—and one of direct relevance to his skeptical approach to doctrinal claims—that there is a big difference between making people realize how tricky it is actually to prove something beyond a shadow of doubt and demonstrating conclusively that it is not true and that they should abandon their belief in it.

Jacoby also touchingly tries to obtain for Ingersoll the reflective glow of others, especially Abraham Lincoln and Walt Whitman—the Colonel is given full credit for admiring them both, and it is repeatedly intimated that he is of their ilk. There are two appendices in The Great Agnostic; the second is Ingersoll's tribute to Whitman, which he wrote upon his death. Jacoby neglects to mention that when Ingersoll actually met the living poet, Whitman went out of his way to affirm his belief in God, the immortality of the soul, and religion as a beneficial force in the world—and to berate Ingersoll for his attacks on faith. Likewise, we are told that Lincoln was Ingersoll's "hero" and that they were very much alike, but not that in the 1860 election (that is, when it really mattered) Ingersoll not only voted and campaigned against Lincoln, but denounced him as a man "of no character." Ingersoll got along better with such men once they were dead. One could go on in this way.

An 'Atheist Pantheon'

If American atheism is a struggling subculture that is still producing hagiographies, it is also a sectarian enclave which is given to its own, alternative, conspiracy-theory views of events. Mainstream scholars have long debunked the myth that Christianity has been historically opposed to science. Even a 20th-century agnostic scientist such as Stephen Jay Gould knew that historical scholarship made such a view untenable. This discredited perspective continues to circulate in the echo chamber of popular atheism, however, and Jacoby has imbibed it.

Worse, in order to illustrate it, she leads with the most damning example she knows: that Christians opposed the use of anesthetics for women in labor because Genesis is supposed to teach that childbearing should be painful. Especially Calvinists, we are informed, believed that "new drugs to ease pain were ungodly." Alas, this is completely an urban legend perpetuated by an ill-informed atheist subculture. If the warfare-of-faith-and-science myth is the equivalent of thinking that President Obama is anti-American, then the anesthetics clincher to prove it makes one a "birther" in another sense. (For a scholarly demolition of this atheist urban legend, see Ronald L. Numbers (ed.), Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion, Harvard University Press, 2010.)

Still, it is hard not to empathize with Jacoby's deep desire to find in Robert Ingersoll a pure and noble atheist undefiled. She longs for an "atheist pantheon" or an "Atheist Hall of Fame." It does not seem, however, that these United States are the logical place to locate such an establishment. If Jacoby were the curator of one for American honorees, one wonders if rather than a pantheon it would simply be a temple dedicated to the cult of Ingersoll. It is not clear who else could be included. She claims that there are two traditions in the American movement: a good one that goes from Thomas Paine to Ingersoll and a bad one that goes from 19-century Social Darwinists to Ayn Rand. It is clear that she has excommunicated those in this second line. (With one doubt clouding the face of a faithful disciple, Jacoby admits that she still finds it "difficult to explain" why Ingersoll himself was willing to give these Social Darwinist heretics the right hand of fellowship.)

Jacoby admits that Paine was not an atheist himself and offers no other American names before or after Ingersoll to fill out this atheist succession. I guess there are some Halls of Fame that cannot find anyone worthy of induction. In short, with such apparently slim pickings, one can see why you would not want to make too much of the fact that Ingersoll had a second-rate mind.

Still Finding Its Way

The first of Jacoby's two appendices is a letter that Ingersoll wrote against vivisection. This is the humane Bob that we all love at his best. Nevertheless, for Jacoby's polemical purposes, it is still a part of her enclave's groundless and twisted conspiracy thinking. She imagines that cruelty to animals was happening because it was "justified by biblical precepts." It is strange to imagine this counter-factual history in which ministers of the Gospel were giving addresses across the nation in favor of vivisection.

Who was actually doing that? The scientists and medical researchers who Jacoby has heroically benefiting mankind by defying and supplanting the clerics. Who actually founded the American Anti-Vivisection Society? Caroline Earle White, an adult convert to Roman Catholicism (a form of Christianity that comes in for Jacoby's special ire.)

Ingersoll's anti-vivisection letter is lovely—ending on the delightful note that human beings should not debase themselves into being merely "intelligent wild beasts"; that they should not deform their "soul" by indulging in cruelty. If one did not know the author you would assume it had been written by a pious Quaker. Indeed, most every social cause Jacoby credits Ingersoll with championing—anti-capital punishment, pro-women's rights, anti-slavery, and anti-corporal punishment—were embraced by Quakers precisely because they wanted to take passages in the Bible more literally than other Christians were doing. To observe that other Christians read the Bible in divergent ways does not seem different in kind to saying that, from my perspective, Ayn Rand is the wrong kind of atheist. And atheist leaders in Communist countries have certainly been enamored with capital punishment and so on.

Then there is Jacoby's running praise for Paine's Age of Reason as a work of "literary skill" that has "stood the test of time." Much of it is actually a puerile anti-Bible rant that reads like the offerings of some self-satisfied sophomore on an un-moderated comment thread. To wit, "Among the detestable villains that in any period of the world have disgraced the name of man, it is impossible to find a greater than Moses." If that strikes you as incisive criticism, there is an intellectual feast awaiting you. The truth, however, is that the masses don't read The Age of Reason anymore: It is actually the Bible itself that has stood the test of time.

I am glad that Jacoby is trying to reinsert Ingersoll into the American consciousness. We Christians know about the traps of hagiography and a conspiracy-theory mentality and therefore cannot judge such faults too harshly. I am also pleased that Yale University Press is willing to try to help along a nascent intellectual community while it is still finding its way.

Timothy Larsen, McManis Professor of Christian Thought at Wheaton College, is the author, most recently, of A People of One Book: The Bible and the Victorians (Oxford University Press).