Editor's Note: Four years ago today, 16-year-old Derrion Albert was walking home from school when he was caught in a brawl between fellow students and beaten to death with pieces of railroad tie. The footage of his death spread quickly on the Internet, igniting a national conversation about Chicago's youth violence, and featured prominently in the 2011 award-winning documentary The Interrupters. The following story is told in Albert's honor.

The video went viral. The boy was dead. The heart-stopping YouTube footage struck Fenger Academy High School in 2009 like the blunt force that took the life of one of its students. At a time when Chicago was reeling from a lost bid for the 2016 Summer Olympics, the violent death of Derrion Albert on the city's South Side became an emblem of its disgrace. And the digital contagion that captured it seemed to boil the complexities in Chicago down to a simple truth: "Fenger High School is what's wrong with Chicago." It threatened the dignity and aspirations of a generation of high schoolers and their families.

It was becoming difficult for anybody to see a life for these students beyond this dark moment. As one of the people working to shine a light, Carolyn Elaine came back to her alma mater with artistic talent, a class in restorative justice, and a desire to help.

Now, four years later, Elaine says, "If you look up Fenger High School today, they have paved the way for what restorative justice in the schools can accomplish. They're calling it 'The Miracle on 112th Street.'

"When you go into that school now, you walk into an environment of peace. It has created a model for what they're trying to replicate at other schools. We wanted to shift the view of the school, and didn't want the way that Derrion Albert died to be his legacy."

Elaine told her story at the 2013 CIVA Conference for Christians in the Visual Arts, held at Wheaton College this summer in the Chicago suburbs. This year's theme was "Just|Art: A Conversation about Making Things and Making Things Right." Conference themes included: Can art do justice? Can artists play a role in restoring a culture? Does making art and making beauty heal a place, a community, a soul? Elaine's story offered one answer.

Time to Go Back

That story began in 1980, when Elaine graduated from Fenger and left the Rosedale neighborhood on the South Side where she had grown up. As she watched every media outlet stream the footage of Albert's death, Elaine said, "I didn't want anyone to know I had graduated from Fenger. This was my high school."

But she realized that she had played a role, "because I haven't gone back to the school or to the community for over 30 years. I got my diploma and was the first in my family to go to college. Then I took a job in Texas—never looked back—even when I returned to Chicago years later.

"I heard God so clearly say, It's time to go home, time to go back. I said, 'Are you kidding me?' "

Elaine was taking a course with Landmark Education, a training and development organization, and was required to create a community project. She says she felt like it was more than the course giving her the assignment.

"Derrion was killed next to a youth center, a community center," she says. "So I went to the youth center and said, 'I'm here to serve. I'm an artist. I don't know how that may be helpful. But I want to do something.'"

Elaine started attending meetings at the youth center alongside vice presidents of U.S. Bank, community leaders, pastors, and the principal of Fenger. They were there to find the best response to Derrion's death. "Going back to that community was like going to a war zone," says Elaine. She told the group that she was a mosaic artist and wanted to do a mural at Fenger. "I declared that I was going to alter the views that had been created around what had happened."

In the first meeting, Elaine swallowed hard and told the group she needed $60,000. Though many in the room met her later suggestions with blank stares, a couple people would always approach her after meetings to ask how they could help. One was a vice president of U.S. Bank. "Can you get me a proposal by tomorrow morning? I have a meeting. I may be able to do something." She got him a proposal. And he got her some money.

"The rest of the money came quickly after that," Elaine says. Over the next few months of the school year, the project raised all its funding and formed important partnerships along the way.

Partnering for Peace

Two key partnerships were with Robert Spicer, dean of a then-new restorative justice program at Fenger, and with the Community Justice for Youth Institute. The grant money came with the stipulation that the project have a restorative justice component. Restorative justice is a method of reconciling offenders and victims in conflict, using conversation and teamwork to rebuild trust and foster peace. Through these partnerships, Elaine was learning that restorative justice addresses three questions: What happened? Who's been harmed? And what needs to be said to repair the harm?

"Those are the exact questions I ask when I go into a community or environment," says Elaine, "because I work with broken people and broken communities." She's led art projects for other Chicago schools, on overpasses next to Chicago neighborhoods, and even another project with Fenger in subsequent years. But the first project with Fenger was giving her a new way to understand the redemptive power of her art. "It gave me a vocabulary for what I'd been doing through my work all these years." (She began her professional artist career 16 years ago.)

Elaine's mosaics are made from pieces of ceramic tile and glass arranged into patterns and images that are grouted largely by the people she works with. "I rarely actually touch the pieces myself, I'm so busy directing and overseeing the work."

A mosaic from grassroots, community-based art making is more than a beautiful object—it is a way for people to be heard. "I call it a visual voice," says Elaine. To understand what the Fenger community needed to say, she began holding "peace circles," a practice of structured group conversation and attentive listening, with over 100 members of the Fenger community. From these peace circles emerged images that would later appear in the mosaic.

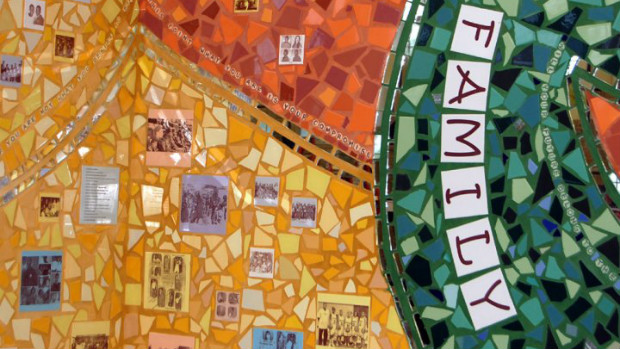

Nearly a dozen students and Elaine designed a mural that told the story of Fenger. They created mosaic tiles that held images from old yearbook pages stretching across the decades, photos of graduating classes of Fenger alumni set amid other tiles bearing the words of current students, and two large sankofa birds on either end with long curving necks facing backwards holding an egg in their beaks. The next step was covering a 700-square-foot cafeteria wall with mosaic pieces of broken glass and broken ceramic tiles using the hands of broken people in the heart of a broken community.

Binding Up the Brokenhearted

Through the long months of making the mural, Elaine was one Christian in Chicago who embodied the spirit of Isaiah 61:

The Spirit of the Sovereign Lord is on me,because the Lord has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim freedom for the captives and release from darkness for the prisoners.

"It's impossible to calculate how the presence and creation of art might have contributed to the positive changes at the school during the last four years," says Elaine. "However, incidents of violence are way down, [and] graduation rates way up. Also playing a part are other efforts under the 'restorative justice' philosophy, which were merged with collaborative art making. Since the 2009 project, other walls of the school have bloomed, the hallways are neat and clean and brightly lit, and art is everywhere, including two more large mosaic murals."

While the mosaic could not restore Albert's life, it could transcend the violence that took it and offer an antidote to the viral YouTube video. And though no bells would be ringing in the Olympics' arrival in Chicago, the mosaic tangibly reminds a community that broken things in loving hands are made beautiful, that beauty is the aspiration of all brokenness, and that no darkness can stand against such things.

"When you look at the work that's created by students, by the community," says Elaine, sitting across from me at the CIVA conference, her face bright as Moses coming down from the mountain—"when you look at mosaics, you can see the beauty in the finished piece, but the story behind the artwork is in the cracks."

It reminded me of the chorus we at the CIVA conference sang at the final worship service:

Ring the bells that still can ring Forget your perfect offering There is a crack in everything That's how the light gets in.

(Leonard Cohen, "Anthem")

Drew Ward teaches Environmental Literature for the Creation Care Study Program and writing at Chaffey College. He has written for This Is Our City about Riverbend Commons, a suburban experiment in intentional Christian community.