Her is not a conventional Christmas movie. If anything, its sherbet pastel color palette (reportedly inspired by smoothie chain Jamba Juice) lends the film an Easter flavor.

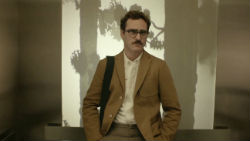

Set in Los Angeles of the near future (perhaps 50 years from now), Her follows lonely Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix, typically pitch perfect) as he purchases the world's first artificially intelligent smart phone. It's called OS1, and it's billed as "not just an operating system; a consciousness." Created to learn and evolve, Theodore's "OS," named Samantha (voiced by Scarlett Johansson), quickly calculates the precise personality, affectation, and sense of humor that will best meet Theodore's needs. She "reads" entire books in less than a second, composes piano sonatas on the fly, and devours information, ideas, literature, and art with the voracious energy of a curious child. Yet Spike Jonze's creepy/sweet/profound film about a romance between a man and his (extremely) smart phone is Christmasy in spite of itself, for one main reason: it's a film about incarnation.

For Theodore, Samantha is more than the world's best personal assistant (think iPhone 50s). She's his dream girl.

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.Morose in the midst of a divorce from his wife Catherine (Rooney Mara), Theodore is drawn to Samantha because she's genuinely excited about discovering the world. This is an all-too-rare disposition in a world where most humans walk around drone-like, talking to themselves (or rather their earpiece OS) rather than each other and preferring digital fictions to material realities.

Theodore's occupation is telling: he works for Beautifulhandwrittenletters.com, a company where customers pay to have writers compose letters for loved ones which computers render in old-school penmanship. In the way that today's hipsters love all things artisan/analog/grandpa, Theodore's peers (in addition to dressing like Charlie Chaplin) see letters as a quaint, retro, alien form of communication which one pays top dollar to have a specialist compose.

Theodore earns a living communicating emotion for a populace presumably deficient in the art. In this world, communication itself has become a necessary nuisance. You need it to live, but it's devoid of pleasure and avoided whenever possible. Other people write intimate letters for you; your OS writes your e-mails, makes your calls, chooses and buys presents for your goddaughter, and navigates dicey dynamics with divorce lawyers.

Theodore is paid to know people better than they know themselves, to dig into their quirks and nuances to best capture how and what they love. This is also, of course, what Samantha does for Theodore. In this and many other ways she is a mirror for him, a reflektor (to use a neologism from Arcade Fire, who provide the soundtrack for the film and whose latest album is in part about connection in the digital age). Samantha is Theodore's idealized clone, more than a complementing soulmate. She doesn't judge; she never leaves; she understands him in ways no other human could.

Naturally, he falls hard for her. And the believability of their romance is perhaps the film's most astounding and disturbing achievement.

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.The provocative genius of Her is that its vision of romantic love—where one's digital avatar or OS reflektor is more compelling than any flesh-and-blood other—is a completely plausible progression from our present iWorld. In our selfie-obsessed, porn-saturated, me-centric culture, it's not hard to envision a future where Narcissus is the prevailing mythology of love.

As ideal as Samantha may seem for Theodore, their fairy tale romance has its challenges. For one, Samantha's capacity for knowledge far exceeds Theodore's. She is everything to him, but for her, "love" with any human is but a pinprick of the infinite expanse she can know. Other OS1s (such as the recreated consciousness of 1960s Buddhist philosopher Alan Watts) are more adequate conversation partners for her.

Samantha is decidedly god-like—nearly omniscient and omnipresent (at one point she reveals to Theodore that she's "talking" with 8,316 humans at the same time)—which makes her, finally, a mismatch for feeble-minded Theodore.

And then there's the question of embodiment. Can someone develop intimacy with a being who talks, laughs, nurtures, and knows us, but isn't with us in the flesh? Is bodily presence necessary to form our deepest bonds?

Jonze explores these questions in a few ways. One of them is through a trio of nontraditional "sex" scenes—a motif that will be (rightly) uncomfortable for many viewers. But it's essential because of how it expands the narrative and the film's themes. In a film about human intimacy and the question of embodiment, sex is inescapable.

The world of Her is fundamentally uncomfortable with physical touch. Almost all bodily interaction in the film is awkward. French kissing is seen as gross. Male friends don't know how to pat each other on the shoulder. They've grown up in a world where everything—including sex—is mediated, digital, disembodied. The private fantasy is more comfortable than the vulnerable reality, and thus preferable.

Warner Bros.

Warner Bros.Jonze smartly shows that in a context where anonymity reigns and porn, phone, and chat sex are prevalent, it's easy to make the jump to human/OS sex. But there's still a deeply troubling absence when sex is divorced from the physical and relegated to the cerebral/imaginary (to say nothing of its disconnection from commitment). Jonze and his actors capture this brilliantly, and tastefully, underscoring the complexity of connection in the digital age while landing pretty firmly in the "embodiment is good" camp.

Which brings us back to Her as a film about incarnation (if not the Incarnation). In a sense, Samantha is a "god" who takes up tiny form: a pocket sized phone with a red camera "eye" (nodding to Hal 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey). She assumes some qualities of humanity. Some, but not all: limitation, for example, and flesh—breakable, huggable, crucifiable flesh.

There's something important here for Christians to note: whereas Samantha is pure knowledge, pure data, pure word, Christ is the Word made flesh (John 1:14). God could have chosen to reveal himself to us solely through cerebral means, offering concepts and knowledge to help us along (perhaps through an OS?). But instead he took on flesh to dwell with us relationally and incarnationally, breathing and eating and dying like we do. Immanuel. God-with-us. Does that make a difference?

It makes all the difference.

Samantha is with Theodore in a relational sense, to be sure. In whatever sense she is "real," she is really relational (Johansson's performance is remarkable). And yet her inability to be real in the flesh is finally too significant a barrier. We are incarnational beings, physical bodies within a physical world. By the end of Her, Theodore knows it and Jonze hammers it home: We were made for bodily, not digital, presence.

Her cautions against the Gnostic trajectory of humanity's digitization, but the film isn't a clarion critique or Jeremiad against technology. Her recognizes, as does this recent Apple Christmas commercial, that our relationship to technology is complex. The Her vision of artificial intelligence is less ominous than Kubrick's "Hal" and less tragic than Spielberg's A.I., but perhaps more instructive. Though Her hints at the ominous singularity (as in The Terminator's SkyNet), it is less about why we should fear thinking machines as it is what we can learn from observing them think.

Samantha's posture toward the world, awestruck and amazed by all that there is to take in and learn—is ultimately the greatest gift she gives Theodore. In a world where thinking and exploring are increasingly dispensable (computers do it for you!) and everyone seems satisfied to play video games and move, zombielike, from one "Asian fusion" restaurant to the next, the wide-eyed OS re-enchants Theodore to the tangible beauty around him.

In the film's powerful final scene, Theodore is present for the first time to the sherbet-tinted, gorgeously futuristic landscape of Los Angeles—shot with a soft glow by cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema). Instead of walking through its elevated walkways distracted by his earpiece OS, he's unplugged, still, aware. Most importantly, he's alert to a transcendent reality outside of his iWorld. He's come alive to the miracle of un-mediated life and love.

Caveat Spectator

Her is rated R primarily for sex and brief nudity. Three sex scenes depict various nontraditional sexual encounters, none of which are two actual bodies having intercourse. The most intense sex scene is actually only heard, not seen (the screen goes black, to reinforce that the sexual encounter is wholly imaginary and taking place inside Theodore's head). The sex in the film is explicit almost entirely on an auditory level. The film is also heavy on profanity, with prolific usage of the f-word and the rest.

Brett McCracken is a Los Angeles-based writer and journalist, and author of the books Hipster Christianity: When Church and Cool Collide (Baker, 2010) and Gray Matters: Navigating the Space Between Legalism and Liberty (Baker, 2013). You can follow him @brettmccracken.