For millennia, biblical literature has shaped imagination and culture. "The Minimum Bible," a project from pastor and artist Joseph Novak highlights that tradition, using graphic design to sum up each book of the Bible in a single image. Curious to pick his brain on sacred art and exegesis, I asked Joseph to share his thoughts on sacred art and interpretation. Enjoy. He's an articulate pastor and sharp conversation partner. -Paul

Paul: We named this site PARSE … obviously we're a little into exegesis around here. What relationships between interpretation and design did you notice through this project?

Joseph: I shall not speak of design generally, for each project exists for a slightly different reason and with greatly different goals. But for this particular project, the design process was itself a function of hermeneutics. The act of reading, sketching, condensing, symbolizing (and then worrying I took it too far), was all a visual exercise of interpretation.

I was making a visual commentary, sort of an image-based version of what Ben Myers did with his #CanonFodder tweets about each book of the Bible. In the end, I hope to have produced not "the Bible" but a visual sidewalk that leads to the Bible. Ultimately, however, I cannot escape the reality that my work is itself an exercise in interpretation; it does not stand in isolation from the text, but remains unapologetically dependent with the text.

I sense you're trying to spark a conversation about Scripture here. What are you saying?

I think we're in an early stage of a revival of the arts within the Christian tradition, particularly among Protestants who have so long feared images as things which may—and often do—misrepresent God. Many younger Christian leaders are taking the time to be educated in the arts, to get to know local artists, and to produce art which is thoughtful, nuanced, and highly engaging.

What is interesting to me is that when placed in front of a John August Swanson work (e.g. "The Procession"), many of these younger Christians intuitively know what to do. They stare, they soak in the details, they search for connections within the image, they literally stand before the work and consider its symbolism, clarity, and profundity. But when you hand them a Bible, they treat it not as art, but as a textbook. They exegete it in a desperate—and futile—attempt to find out the one and original meaning the author intended.

What could the Christian church stand to gain from viewing Scripture as art? How could it benefit us to learn how to stand before Scripture as an awed, impressed, worried, and grateful people? This is not to say that we do not need to study Scripture. Art students certainly study artists and art making processes. But, in our liturgies and services of worship, how would it transform homilies and sermons for the preacher to stand before the text as a visitor to the Louvre stands before a Da Vinci or a Raphael? I think far too often, preachers stand not as grateful benefactors of the art of Scripture, but as the art critic anxious to show every problematic brushstroke or the lines of redaction where another artist took over for a while. If real transformation is to occur, then congregations need an encounter with the living Word who speaks to the church whenever the Bible is read and proclaimed.

The images are invitations back into what Karl Barth called the "strange world of the Bible."

The images in my series are really invitations back into what Karl Barth called the "strange world of the Bible." My images make no claims of being exhaustive or comprehensive; they are but one interpretation of the biblical books. I've heard from several folks on Twitter things like, "Not what I would have done" or "I would have chosen something else to emphasize." My reply? Great. I'm really beginning a conversation about themes and symbols in the text. Scripture, like good art, requires interpretation. And the beauty of our post-enlightenment era is that we tend to understand that the texts of Scripture are themselves multivalent, possessing layers of meaning, and we need multiple modes of retrieval to understand their complexity. Perhaps art is one underutilized mode.

As a pastor, do you think we need to reconsider popular ways of reading the Bible?

As a pastor, I think we need to reconsider the privilege of reading the Bible alone, seeking one's own interpretation, based on one's own preconceptions. Instead of encouraging our parishioners to go and read alone, let's try inviting them to come and read together. Getting people together to read Scripture and study it well pushes us into a way of reading Scripture that is more about discerning what the text means for us today than it is about debating my "view" over against your "view." Reading the Bible well means reading the Bible together, in Christ's name, in the context of worship, alongside those whose political, socio-economic, or theological views are different from your own.

Instead of encouraging our parishioners to go and read alone, let's try inviting them to come and read together.

It's not an "anything goes" hermeneutic, however. Too often, I think we allow space for interpretations which are invalid. A blue square on a white field, for example, may be interpreted as many things. But to say, "The square is orange which I think symbolizes the warmth of the sun" is invalid. It is beyond the boundaries of validity, because, as we all know, the square is not orange. Similarly, sometimes, Protestants have permitted too many "orange-square" interpretations because we were fearful of resembling a neo-Magisterium. Part of reading the Bible together means that we are opening ourselves up to the possibility that there are better, more helpful, and ultimately more faithful readings of a text than we might get at on our own. Pastors, as guides of these discussions, had better be prepared to navigate these conversations, well-versed in the history of Christian interpretation and insight.

Why do you think pastors in our culture often favor a "zoomed-in" approach versus more large-level, pattern focused readings?

First, I would say that the "zoomed-in" approach and the "pattern-focused" approach you

mention are not necessarily diametrically opposed. We need both solid exegetical work and thoughtful pastoral application, otherwise our preaching either becomes a recitation of our exegetical notes or a "Stories from Lake Wobegone"-esque moment.

Second, though, I think that some pastors in preparing a sermon get out their archeological pickaxe and dig down deep into the exegetical intricacies of the biblical text. They've got their Greek down pat, their BDAG in their backpack, and their favorite biblical atlas tucked away, just in case. The only problem is that once they've made these discoveries, they often lack the ability to bridge the chronological gap between the text and their congregation. They assume that everyone else has their Greek down pat, their own BDAG in their backpacks, and their atlases ready to use. But biblical illiteracy is an increasingly pronounced issue for the Christian church in America—and not just in mainline churches. Like Irenaeus advocated in the second century, we are ever in need of a Rule of Faith to help us assemble the confusing mosaic tiles of Scripture. We need to zoom out and say: What is the bigger story here?

What's your personal favorite of the images you produced? Tell me about the image.

This is like asking me to pick which of my children is my favorite! Impossible! I think as far as representative images—ones that could serve as examples of the project—I would want to point out "Genesis" and "Job."

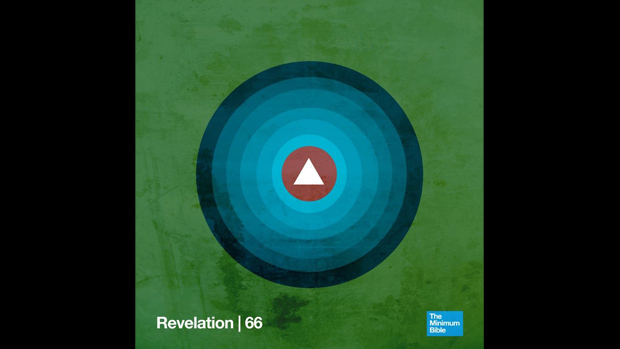

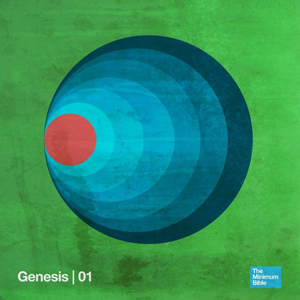

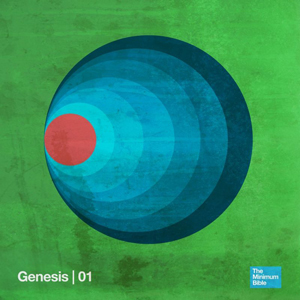

In the "Genesis" image [above], six blue concentric circles are arranged on a green field, their left edges aligned on the left of the page. A seventh circle—red—is placed inside the smallest circle. This is the first book of the Bible, and it is ultimately an origin story—it is the back-story of the group of people who at the time of its composition are living and writing in Babylon—landless, kingless, and temple-less. How did they get here, what happened? At its heart, the story is really a brief image in the reflecting pool of Utopia but by the third chapter, a stone has been tossed into the pond and the ripples of that stone spread throughout the rest of the book.

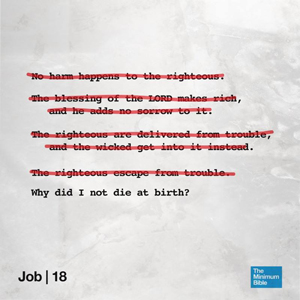

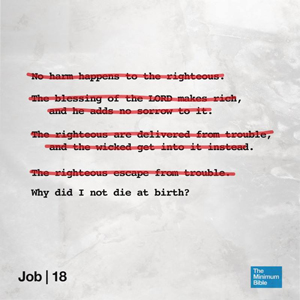

In the "Job" image, four statements each taken from the book of Proverbs are written and crossed off harshly in red ink. All that remains is the fragment of Job's early lament: "Why did I not die at birth?" One of the striking literary aspects about Job is how it basically functions as a rebuttal of much of the other Wisdom literature. In the Hebrew Bible, Job is grouped in with Psalms and Proverbs in a subdivision called the "Book of Truth (EMETH, in Hebrew, one consonant each for Psalms (T), Proverbs (M), and Job (E)." And while Psalms and Proverbs are both relentless in their confidence that God will not unfairly burden the righteous, but punish the wicked, Job is included as a reminder that this is not always the case, that sometimes the righteous do suffer, and sometimes it falls outside our perception to understand why. So for my design, I wanted to be sure to include this literary perspective on Job by referencing other Wisdom literature and showing how Job is essentially crossing off those fragments as "questionable guarantees."

What did a "minimal" reading of the Bible do for your own views of Scripture? For your soul?

The Bible is filled with countless metaphors and images that the writers employ to help the reader make sense of the revelation before them.

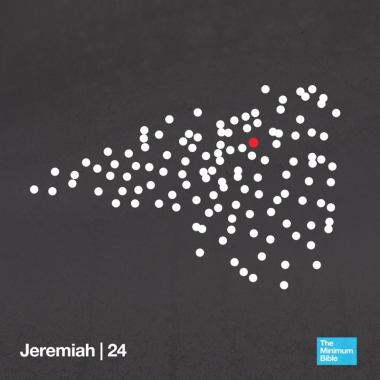

I think it helped me open myself up a bit more to the symbolic world of the Bible. The Bible is filled with countless metaphors and images that the writers employ to help the reader make sense of the revelation before them. Fires on mountains, locusts, a man swallowed by a fish, the building of a structure, the tearing down of a structure; all these may have realistic counterparts in the present world, but in the text they often occur symbolically. The temple, for example, was a real and magnificent structure, but it was always about more than the building. The building was the symbol for the fixed presence of God, accessibly present to the people. When it was plundered and destroyed, the depth of pain was more than just for the loss of a building. The loss of the symbol was most egregious.

In trying to shape the text into a symbol, I found myself realizing that the Bible itself is a symbol; it is a symbol of God's desire for self-revelation. We hold in our hands a Book that professes the story of a God who opened himself up to the human race and, insofar as Christians read it, eventually entered the story and was killed as a human being. When we say in worship: "This is the Word of the Lord," it should go without prompting that our hearts would be filled with thanksgiving, for we are being offered a piece of God's story as a symbol of hope that God has not abandoned the world he shaped, but is still speaking to us today.

In our church, we place the open Bible on the table next to a pitcher of water (baptism), and a plate and chalice (Communion). We do this to show the interconnectedness of the Word (symbolized by the Bible) and Sacrament (pitcher, plate, and chalice); all are instruments by which God's Spirit speaks to the church and we try to portray them as such. So when the pitcher is poured into the font as it is each Lord's Day, and when those same dishes are used to hold bread and wine as it is when we celebrate the Sacrament, and when the same Bible is picked up and read out loud as it is each Lord's Day, the congregation is making symbolic connections of the multifaceted nature of God's self-communication. For me as pastor, picking up each of these symbols offers different nourishment; the pitcher speaks of the forgiveness of sins, the Bible speaks of God's desire to speak to me, the plate and chalice speaks of Christ's righteousness offered in place of my own. Welcoming these symbols back into our church architectures has certainly afforded more depth in pastoral conversations, but also in my own devotional life.