In a culture all mixed up about judgment, how can Christians model a path between anything-goes apathy and bloodthirsty outrage? Seeking an answer, A.J. Swoboda puts an ear to the ground. Listen with him for the voice of blood.- Paul

Whether you paid attention or not, many of us watched the world mercilessly turn against a man this past spring. Donald Sterling, the now ex-owner of the NBA's Los Angeles Clippers, became a poster-child for racism, hatred, and bigoted wealth. Sterling's racist, thoughtless comments, recorded secretly and posted on a gossip website after lots of money changed hands, reveal a man whose words and actions betray his very character and his future. Sterling was banned from the NBA for life for his comments, and fined 2.5 million dollars. Reactions of outrage, even outright hatred toward him were everywhere online.

There is no excuse for his comments, no justification—by any stretch of the imagination—for the opinions that spawned them. But from my perspective, our culture's reaction, angry and judgmental, reveals something deeper and darker than simple righteous indignation. It reveals how broken our sense of judgment is, and how much we need a better one.

Judging judgment

The mantra of American culture is that judgment is bad.But then, as it talks out of one side of its mouth, it turns hypocritically around and judges without grace the words and actions of someone it deems to be wrong.

The mantra of post-modern, post-Christian American culture is that judgment is bad. Keep your judgment to yourself, it says. After all, who am I to judge? But then, as it talks out of one side of its mouth, it turns hypocritically around and judges without grace the words and actions of someone it deems to be wrong. Did Sterling deserve a strong reaction? Was he wrong? Without question, yes! But can we really say Who are we to judge? when we do what we do to the Donald Sterlings? No.

Our culture needs to admit that we all judge. But for that to happen, the church must demonstrate that judgment, done in the Spirit of a graceful Jesus, is needed for human flourishing. Without judgment, hatred, rape, murder, and racism would go unchecked. But to avoid the hypocrisy that undercuts the true purpose of judgment, we need to re-learn the art of graceful judgment.

The cry of injustice

Judgment, in the end, is ultimately God's.

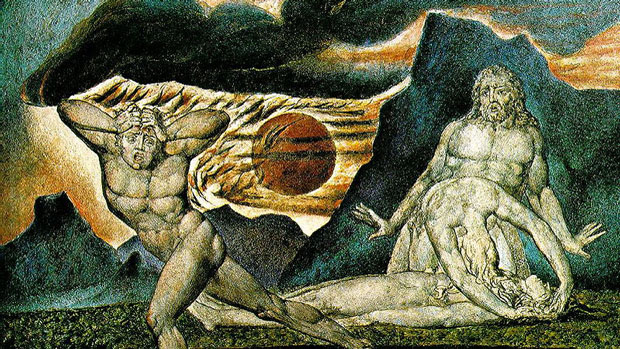

The tale is well-known: Cain, jealous that his brother Abel's sacrifices are acceptable before God while his own are not, lures Abel into a field outside the city. There, Cain commits the first murder in the Bible. (As a disturbing aside, remember that the first murder recorded in the Bible is a religiously motivated murder.)

God saw, and God visits Cain. God asks, "Cain, where is your brother?" Cain's response, like Adam and Eve's before him, is deflective: "I don't know. Am I my brother's keeper?" (Gen. 4:9). The Lord replies quickly and pointedly: "What have you done? Listen! Your brother's blood cries out to me from the ground" (Gen. 4:10; italics mine). In Hebrew, Abel's blood was tsa`aq; it "cried out" the way Israel would later "cry out" to God in Egypt. God is not only aware of Abel's murder but can actually hear his blood crying out, seeping into the ground.

Then God curses Cain.

Abel's blood screamed out for justice, crying out for rightness, for righteousness. But why must we linger on that point? Because injustice will always cry out. Injustice will not hide. Injustice will cry out until wrongs are righted. And the blood will not shut up until it is. Thomas Dozeman has pointed out that once Abel's blood falls to the earth and is no longer in its proper place, it becomes a kind of pollutant rather than a life force in Abel's body. As Dozeman puts it in The Priestly Vocation, blood becomes a "virus" infecting the story of creation from that story on.

But in the great story of scripture, the blood of Christ becomes a kind of reversal of this viral hatred. The Gospel stories about Jesus of Nazareth not only rely upon such narratives like Cain and Abel, but actually build upon them as a kind of narrative backbone. Jesus, like Abel, made religious people squirm—he infuriated the Jewish leaders with his ability to inspire the crowds and speak of his intimate love of his Father. They grew jealous at him. He infuriated them all the more by instructing them that righteousness, righteousness embodied, was among them. He was that righteousness: "I am sending you prophets and sages and teachers. Some of them you will kill and crucify; others you will flog in your synagogues and pursue from town to town. And so upon you will come all the righteous blood that has been shed on earth, from the blood of righteous Abel to the blood of Zechariah . . . whom you murdered between the temple and the altar" (Matt. 23:34-35). Jesus' blood would be the most righteous blood of them all.

Not unlike Abel's blood, the blood of Jesus cries out to God eternally on behalf of creation. It cries forgiveness, love, peace, and acceptance. And that blood calls out to us as well.

Jesus, like Abel, was not received by his own (John 1:11). In the end, Jesus was taken outside the city by his Jewish brothers where he would die on a Roman cross, blood dripping into the cracks of the sun-scorched earth. His blood, like Abel's, still cries out. And not unlike Abel's blood, the blood of Jesus cries out to God eternally on behalf of creation. It cries forgiveness, love, peace, and acceptance. And that blood calls out to us as well. It pulls at us. It calls to us. It disturbs us. It whispers to us.

Paul describes Jesus' blood as the blood of divine reconciliation, a sacrifice that tears down walls of false separation. We have been, as the Pauline letter to Ephesians says, "[B]rought near by the blood of Christ. For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility" (Eph. 2:13–14).

Is it possible that the blood of Christ that fell upon the earth could heal even the enmity between Cain and Abel? It could reconcile us to God—why not Cain to Abel?

Is it possible that the blood of Christ that fell upon the earth could heal even the enmity between Cain and Abel? It could reconcile us to God—why not Cain to Abel? Could Jesus' blood break down that dividing wall of hostility? Miroslav Volf, in a provocative reflection on the reconciliatory power of the coming age ushered in by the sacrifice of Jesus, argues that it will be in that coming day where enemies will be made right. In that day, righteousness will prevail. It is there, in resurrection reconciliation, that Cain and Abel will once again face each other. Volf writes in The Final Reconciliation,

If Cain and Abel were to meet again in the world to come, what will need to have happened between them for Cain to not keep avoiding Abel's look and for Abel to not to want to get out of Cain's way? . . . If the world to come is to be a world of love, then the eschatological transition from the present world to that world, which God will accomplish, must have an inter-human side; the work of the Spirit in the consummation includes not only the resurrection of the dead and the last judgment but also the final social reconciliation.

Volf points out that once, when Karl Barth was asked if we would see our loved ones in heaven, he glibly responded: "Not only the loved ones!"

Judging gracefully

When Karl Barth was asked if we would see our loved ones in heaven, he glibly responded: "Not only the loved ones!"

Judgment is God's. In the final reconciliation, justice and judgment will be served—justice between the oppressors and oppressed, murdered and murderer, perpetrator and perpetrated. Perhaps that is why John's Revelation looks forward to that day as a day when, "He will wipe every tear from our eyes. There will be no more death or mourning or crying . . . for the old order of things has passed away" (Rev. 21:4; italics mine). John knew we will enter the heavenly dimension with many tears from a life of crying and mourning. He also knew, however, the tears will be wiped away.

What does that say to us about how we judge today? First, we need to learn to judge humbly. Jesus said that in the same way we judge, we will be judge (Matt. 19:28). That means: If you judge with no grace, expect the same. If you judge with grace, expect the same.

I must practice humility in judgment. So must you. As a Christian pastor, I know unequivocally that there have been conversations that I've had (you've had them too) in quiet places, that if recorded and published would get me fired, judged, and hated. When we judge, we should judge gracefully. We are people who have hearts as dark as any.

Second, we must recognize that no hatred, no bigotry, no racism will go unchecked forever. But that ultimate judgment is God's.

Jesus' blood is so powerful, so majestic, so able, that in the final reconciliation, if Donald Sterling and Magic Johnson were to submit their lives to the Lamb who was slain they would be so covered in love, forgiveness, grace that they could (and will) share iced teas by the pearly gates. Jesus' blood is that powerful.

Powerful enough for you, and the enemies that you have managed to make, to be drawn near. So if you judge the Donald Sterlings, remember that the very thing you hate is alive in your bones as well.

Judge gracefully.

A.J. Swoboda is a pastor, writer, and professor in Portland, Oregon. He is @mrajswoboda on Twitter.