Betsy Brown

Betsy BrownWhen I was sixteen, my family attended a church that met in a movie theater. I sang worship songs, listened to sermons, and took communion in the same building where I had seen The Pirates of the Caribbean and Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. Strangely, at the time I cared very little for movies, and even less for church. Then, after I graduated from high school, I began to fall in love with both the cinema and the cathedral.

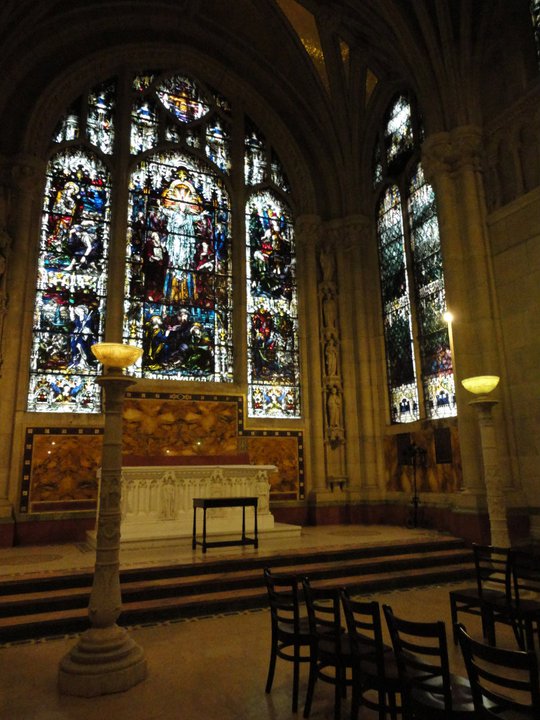

It started as a love for the buildings themselves. I lived in New York City. Movie theaters of all shapes and sizes abound, and they intrigued me: the ten-story windows and mountainous elevators of the cinemas along Broadway, the velvety seats and old-fashioned curtain in the Paris Theatre near Central Park, the intimate poshness of the theaters at the Film Society of Lincoln Center. Churches amazed me even more: the ornate stained glass of Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, the cozy, vine-entwined courtyard in front of 29th Street’s “Little Church Around the Corner,” the eccentric vastness of the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine.

For the practicing Christian, church attendance is a vital part of life. Movie theater attendance may not be, for all of us. But I have recently been thinking about how our approach to movie-going can inform our approach to church-going, and vice versa, and for those of us who enter both buildings on a regular basis, I want to make a few connections.

The architecture of the church and the cinema may vary from place to place, but whether ornate or not, the structure of the buildings promise something lovely to come. We enter doors into a large, dimly-lit room. It is a hushed, open space. We sit side-by-side. We hear music. We hear carefully-chosen words. We see a place that has been set with care, a place meant to be beautiful.

Betsy Brown

Betsy BrownThis aesthetic finger points toward the story that unfolds in the space—the story of the film, the story of the liturgy. Each story is new, but it is also very old. As famous screenwriter and teacher Robert McKee says, stories in film help us discover what it means to be human by wrapping a universal experience in a culture-specific expression.

I remember taking the crosstown bus this past winter the Upper East Side to see Spike Jonze’s latest movie, Her. I won’t spoil the plot, but I remember walking out two hours later with a deep sense of gratitude. I looked at the city and the people on the bus around me and decided that, thanks to a sci-fi romance about a talking computer, I knew just a little bit more about what it means to be human.

That next day, Sunday, I took the crosstown bus again and entered a large old cathedral on Park Avenue. It was Advent. I hadn’t grown up in a congregation that followed the church calendar, and I had only been slinking back into churches within the past few months, so the reverent old traditions fascinated me. I watched the pastor light the candle and thought about the giddy anticipation the community felt as they prepared to celebrate Christ’s birth. I had begun to think of church, too, as participation in a story. Just as I had after Her, I walked out feeling grateful.

“Liturgy,” says Anglican writer Urban T. Holmes III, “is an expression of the experience of God at various levels. It is like a parfait, constructed of a series of layered images. Those at the top reflect the current times, while those at the bottom contain the primordial memory of humankind.” How similar this statement is to McKee’s about films as universal human conflicts so true to humankind that they journey from culture to culture.

Betsy Brown

Betsy BrownOne of the biggest mistakes we make as movie-goers and church-goers is thinking that we attend in order to be entertained. Entertainment is a passive process: we sit and wait for moments of amusement. I would argue that both film and church, although they often are pleasurable and entertaining, serve a higher purpose. They have the power to transform—to drive us to action. And, of course, with this transformation can come a far more lasting joy than mere entertainment can give.

I can’t resist using my seven year-old self’s greatest inspiration as an example—Disney’s Mulan. I remember sitting, transfixed, watching Mulan climb to the top of a hundred-foot pole to reach an arrow. She was the only soldier who was able to complete the challenge. After seeing the movie, I remember going on a bicycle ride around my neighborhood in small-town Ohio. I remember singing the songs to myself and deciding that I wanted to become a person who could take on challenges. In second grade, on my grandma’s antique bike, I decided that someday I wanted to learn what it meant to be courageous.

Seventeen years later, on Easter Sunday, I was standing with a hundred other churchgoers in the pews of my old church on Park Avenue. A part of the church’s weekly liturgy was a sung rendition of the Lord’s Prayer. As the choir sang the kingdom and the power and the glory forever, I was moved, and wondered to myself, this is the first Sunday of the rest of my life. After seven years of sneaking warily into churches every few months, I knew I wanted to stay and be a part of the story.

A sensitive liturgy constitutes a living and active Christian community. This life, this action, is worship. And if we open up a place for films to work in us the same way, this, too, is worship. I am grateful for these spaces. They have taught me how to live.

Betsy Brown (@betsykbrown) will receive her MFA this year in Creative Nonfiction Writing from Seattle Pacific University. She writes and teaches in Phoenix, Arizona.