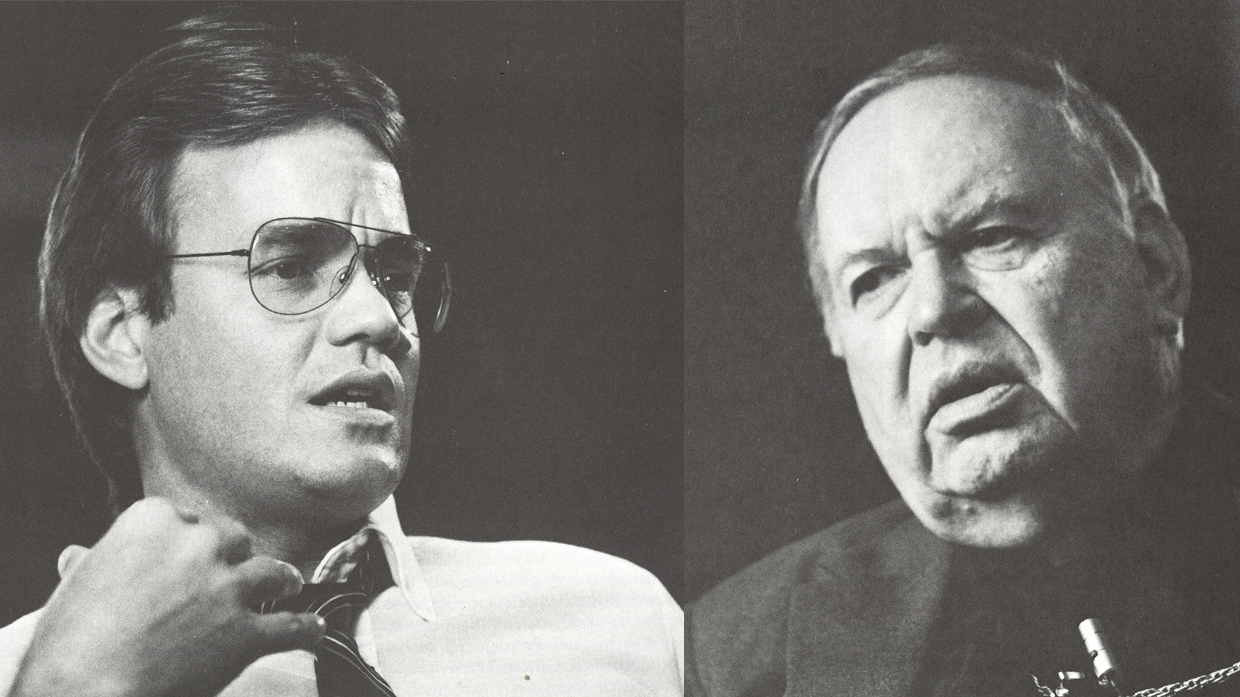

We are highlighting Leadership Journal's Top 40, the best articles of the journal's 36-year history, presenting them in chronological order. Today we present #32, from 1985, the first time a young pastor named Bill Hybels appeared in our pages.

Preaching has changed a lot since Oswald C. J. Hoffmann first stepped behind a pulpit in the 1930s. Or has it? Is the art of persuasion constantly evolving along with the culture or not?

We weren’t sure. So we decided to invite the venerable Hoffmann, now entering his fourth decade as radio speaker for “The Lutheran Hour,” to sit down and interact with a communicator half his age. Bill Hybels first attracted notice in the early 1970s for an explosive youth ministry in the Chicago suburb of Park Ridge; then, ten years ago he founded Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Illinois, where some six thousand now worship on an average Sunday.

The seasoned veteran and the Laser Age innovator—together they explored what persuades audiences to embrace the truth and act upon it. Leadership Senior Editors Dean Merrill and Marshall Shelley posed the questions.

Leadership: Is persuasion an honorable endeavor, or is it just a fancy term for trickery?

Hoffmann: Certainly it’s honorable, if what you are doing is persuading people there’s such a thing as good news. Most of the time these days, people think there’s only bad news.

You remember those jokes, like where the doctor comes in and tells the patient, “well, the bad news is this: We amputated the wrong leg. But the good news is that the other leg is better than we thought, and you’ll be able to get around all right on it.” What’s funny is that it’s all bad news.

It takes a lot of persuasion to convince people otherwise.

Now there is some bad news about persuasion itself whenever it becomes manipulation. People are turned off by any kind of sham. They sense it right away—maybe in the words themselves, or in the tone of voice, or in subliminal impressions. Sometimes they say, “This fellow doesn’t believe what he’s saying himself.”

The apostle Paul made it quite clear he was not going to persuade people with fancy words and eloquent speech. Truth is not found there, he said in 1 Corinthians 2. Look for it in the reality of human life, in the one real person God sent into the world.

What is a minister? Simply a witness to Jesus Christ. The apostles learned this very early.

Leadership: How so?

Hoffmann: Take Acts 17, the Mars Hill incident. Paul found out you don’t argue people into the faith. You don’t persuade them with a philosophical argument. He tried, but he wasn’t very successful.

I don’t mean that argumentation has no place in Christian thinking, but it’s not what persuades. People are persuaded—whether they’re university professors or the retarded—by hearing the real story of Jesus Christ. My experience with the college population is that they don’t come to church to hear a philosophical discussion; they get plenty of that on campus. They come to hear the gospel, straightforwardly told and personally believed. The gospel has its own persuasion.

Hybels: I really affirm that. In 1 Corinthians 1, Paul says ministers have to be willing to become foolish and deliberately take their hands off the oratorical skills and tricks and sleight of hand. We have to exhibit personal faith in the work of the Holy Spirit.

This is exceedingly difficult for a pastor. It strips us bare. It puts us out on the limb of faith, deliberately choosing to become less of a participant in the presentation, relying on God to honor his Word.

Imagine a guy who goes to school eight or ten years to become an expert in oil drilling. He really knows his stuff. People come to his seminars to listen to the intricacies of all the new developments. The speaker can pride himself on the fact he knows more about oil drilling than anybody else in the room. He waxes eloquent in front of the group, uses all his special terminology, and gets the accompanying ego strokes.

We pastors stand in front of congregations, and in our ear we hear the Holy Spirit whispering, Look, just present the gospel. Trust me to work. The gospel itself has explosive power to effect change in human life.

And we say, “But where’s the ego fulfillment? I mean, how am I going to walk out knowing I’ve shown my stuff?” It’s hard for us to take our hands off the gospel.

Leadership: So you would not like to be called a persuader?

Hybels: I didn’t say that. I do have to persuade people that what they have heard about the gospel heretofore has probably been jaded. Most visitors to our church think they’re already Christians because they’re “good people.” I have to persuade them to let the Bible determine who’s heaven-bound and who’s not. That takes a lot of undoing of previous thought patterns.

I also have to persuade them that this ought to be a front-burner issue. In a here-and-now culture, if something doesn’t give me instant gratification, a chill up my spine, a bonus at work, or some fleshly pleasure this weekend, it instantly goes on the back burner. I have to persuade people that eternity is hanging in the balance and ought to be an up-front issue. But when I get to the point of declaring the gospel itself, it’s time to take my hands off and let the message be what God intends it to be.

Hoffmann: At that point, we cannot afford to get impatient. It takes a long, long time for some people to be persuaded, and God works in his own way, but always through the gospel. There’s no special trick. People eventually see Jesus Christ not just in some philosophical frame but as the promised Messiah. They come to see him as their Savior from what oppresses them at the moment. Here is forgiveness. It’s real, and it’s free…. But of course, it also has its price.

Leadership: Have there been times when either of you have found yourself enhancing the gospel, adding to it in an attempt to make it more persuasive? What are the boundaries of persuasion?

Hybels: If you intend to stay in your church very long, you learn quickly you have to live with the responses to inaccurate claims about the gospel. If you promise too much, the guy who comes and receives the Lord is going to be in your study three weeks later saying, “What gives? You said health, wealth, and happiness—and it hasn’t happened yet.”

Most of us are careful about this. But what haunts more of us is, as a friend puts it, “Do we have to tell seekers about the lions?” In the early centuries of Christianity, if you received Christ on Sunday, you might be in the Colosseum by Thursday. Do we tell those barely interested today about the lions awaiting them tomorrow if they become Christians? Do we say, “Here is God’s free gift—but once you receive it, you will be called to deny yourself, take up your cross, and follow Jesus Christ every single day the rest of your life”?

The more we say about these things, the more we begin to color the gift. It becomes a gift with strings attached.

I, for one, feel I have to explain what God has in mind for people after they receive the gospel and begin to walk with him. It’s only fair to state that God has every intention of conforming you to the image of Jesus Christ, and he will chastise you in order to do that. But he will always act with your well-being, character development, and usability in mind. He will not treat you capriciously or banter you about for cosmic grins. He will deal purposefully with you; you are his workmanship.

This has to be articulated if a person is going to make a responsible decision about the gospel.

Leadership: What persuasive techniques do you find distasteful?

Hybels: Not allowing people time to make this decision. Presenting the gospel in a public setting and then saying, “You must decide right now before you leave this place—the Bible says, ‘Now is the day salvation….’”

Leadership: Like the salesman saying, “Special price this week only!”

Hybels: What if the guy has been living with a secular life view for forty-five years? Now in forty minutes he has heard something completely different. Let him catch his breath! Let him think it over, see the implications, ask questions, talk with others about it.

If you force him to make a decision in forty minutes, he may say no, not on the basis of the gospel but on the basis that he didn’t have enough time to give it adequate thought.

In presenting the gospel, I always say, “If you need more time to let the implications seep into your mind, if you have questions you need to have answered, if you have mini-dialogues floating around your head that you need to pursue with someone a little more knowledgeable on this subject—then do that. Just don’t let this become a back-burner issue. Keep it on the front burner. We’re willing to stick with you for as long as it takes, because we know we’re asking you for a monumental decision.”

Hoffmann: It takes a lot of confidence in the gospel to do that.

Leadership: Do you think North American audiences are getting harder to persuade as the years go by, or is that just a myth?

Hoffmann: I wouldn’t say so. In fact, a materialistic age seems to build up its own contradictions and reactions, which provide fertile soil for the flower of faith. I really don’t believe any condition of the world is impervious to the power of the gospel.

Leadership: So when you were a younger minister, you didn’t necessarily have more receptive audiences than you do today?

Hoffmann: Not at all. I was working with college students back in the early forties, and they wanted to know the gospel—but I wouldn’t regard modern student bodies as any less eager to hear. Students back then thought of themselves as sophisticated, too. In fact, many of them wanted to argue philosophy. I don’t find that true today. Current students have neither the time nor the interest. They just want to know what you’ve got to say.

In the last election, I heard several politicians say university campus stops were a relief, because at least they listened to you and received you politely. They weren’t sitting there insisting on certain code words.

Humanity has not reformed itself all that much that it can’t listen to God’s message. Some will say, as they did at Athens, “We want to hear you again on this subject” (Acts 17:32). Others become the Dionysius and Damaris and the others who formed the nucleus for a growing community of believers in Jesus Christ.

We just have to tum the gospel loose.

If I were doing things over, I might preach with less apology than I did at the beginning of my ministry. If you’ve ever sold things door-to-door and succeeded at it, you came to believe that people weren’t doing you such a favor to open the door and listen to you; you were doing them a favor.

Hybels: That’s right.

Hoffmann: And that put a whole new light on things. You didn’t mind making the tenth call after nine turndowns, because the tenth one made your day.

Well, it’s the same with the gospel—it surprises you all the time.

Hybels: There comes a certain point in the life of most ministers—at least I hope it comes—where something kind of snaps inside, and they say, “That’s it. I am not going to apologize anymore for being God’s person or speaking God’s truth. I’m not ashamed of it. I’m not going to shrink back. God has commissioned me. He’s enabled me. I am just going to speak it out.”

I can spot the point in my own ministry when that happened. It was put-up-or-shut-up time. I said to myself, “Either I’m going to be God’s man and speak God’s truth, or I’m going to spend my life worrying about peer approval, congregational approval—and there’s no peace in that.” There’s no rest in being the world’s man, because you’re taking votes every day, reading the Nielsen ratings every Monday morning.

Leadership: How long had you been in the ministry when you finally reached that point?

Hybels: I’d been a senior pastor about five years.

Hoffmann: What brought it about?

Hybels: A series of complications—a few staff members had left, which caused some unrest in the congregation—and it was about then that I came to believe the only way this congregation was ever going to become a moving power for God was to be God’s people. And the only way they were going to become God’s people was to be led and taught by God’s servant.

Three hundred years ago Richard Baxter said, “Men will never cast away their dearest pleasures upon the drowsy request of someone who does not even seem to mean what he says.” People today clutch things tightly—their money, their relationships, their ambition—and here we are trying to encourage them to clutch the Lord. We’re saying God should be the object of their greatest affection.

So I decided: No more drowsy requests. No more apologies. Those will never pry men loose from their dearest pleasures, says Baxter. It was time for me to say, “I have decided to follow Christ. It has had great payoffs in my life, and I challenge you to make same decision. Test God in this matter.

“If you don’t like it being stated this way, that’s fine. If you do like it, that’s great. Either way, this is my responsibility.”

Hoffmann: Randolph Crump Miller, well-known professor of religious education at Yale in a former generation, is said to have remarked that he was persuaded to enter the ministry by the worst sermon he ever heard in his life. People assumed, of course, that he became a minister in order to improve the situation. No, that was not it. The sermon actually persuaded him to do something. It rocked him.

I still don’t know what made it the worst sermon he ever heard; it would be interesting to know. But regardless, it accomplished something strategic. Pastors should be comforted to know that every sermon doesn’t have to be a masterpiece.

Hybels: God can use a lemon.

Hoffmann: Yes. That’s happened to me too. I remember those weekends in the pastorate with two weddings on Saturday and an unexpected funeral on Saturday morning. Every preacher knows the feeling of not getting to finish the customary preparation, not getting two or three hours at the end to polish the words and phrases so they have movement and transition. Some Sundays you just have to go preach what you’ve got in the amount of time you had available . . . and one person after another going out of church will stop and say, “You know, that sermon was just for me.”

When that happens, I have to say to myself, There’s a good lesson here for me. I’m not the persuader.

Leadership: It frees you from the tyranny of having to hit the ball out of the park every Sunday morning.

Hoffmann: That’s a good illustration. I used to play baseball, and when I watch major-league games today, I cannot understand for the life of me why a team can get three men on base with no outs—and then nobody can even lay wood on the ball! They’re all striving to hit a home run.

The great pitcher Robin Roberts once said, “Hitters are dumb.”

And Stan Musial responded, “He’s right.”

We preachers need to realize that in a lot of situations, a clean single would do just as well. Even an infield hit. At least we’d be on base.

Hybels: Yes—but saying that is a little dangerous, because some pastors don’t even take batting practice. I’ve met some who aren’t even trying for singles; they’d rather not even go up to bat. Some golf too much. Others do too much administration, too much counseling, too much of everything but what God has called them to do.

When it comes to message preparation, I feel more pastors are slothful than overprepared. When I ask, “Honestly, how much time do you spend each week preparing messages?” pastors often tell me four hours. I’m amazed at how many start their preparation on Saturday. That’s deplorable. You don’t get a church from serving fast food.

I shouldn’t lay all the blame on pastors, I realize, because in many cases it’s the elders or the congregation that expect all the counseling, visitation, weddings, funerals, organization, administration, and financing, while still expecting great food from the pulpit. They can’t have it both ways.

Hoffmann: In other words, you feel the day of preaching is not over.

Hybels: I’m afraid it’s drawing to a close—and I’m trying to do everything in my power to prevent it because preaching is absolutely central to the development of a vital church.

To return to the baseball analogy: I was a pitcher in high school, and the coach would take us pitchers into a classroom occasionally and say, “Now look: I can’t say this in from of the whole team, but among us pitchers, let’s just talk. Pitching is 85 percent of baseball.”

I say the same thing to pastors: “Preaching is 85 percent of the game. If you’re trying to build a church, preaching is what will make or break it.”

Hoffmann: I would question that. Yes, I believe in preaching, but I have seen parishes where great spiritual depth and conviction were expressed by the pastor in other ways. The congregation so appreciated that depth they forgave him for not being the best preacher in the world.

Hybels: Would you agree that those are more the exception than the rule?

Hoffmann: Yes, but the qualities I mention are essential. There are various ways of persuading, and preaching’s not the only way.

Hybels: I didn’t say preaching was 100 percent. But would you say it’s the primary way?

Hoffmann: It’s very important. But I have a hunch that what you are, Bill, is probably as important in this congregation as what you say.

Hybels: No doubt—but that’s a part of my preaching. I don’t mean to limit preaching to what comes out of my mouth. Preaching is a reflection of who I am in Christ as well as what I say about the Word.

Hoffmann: Some pastors are uptight in the pulpit or have an artificial way of preaching, but they’re very natural in personal conversation. What comes through is what I like to call the gospel personality. Their whole person bespeaks good news.

Leadership: Is negative persuasion—for example, the fear of hell—out of bounds these days?

Hoffmann: I don’t think hell was ever intended to persuade anybody. But it’s a threat that hangs over us nonetheless. So is death.

When we speak about either one, we simply point out the shadow hanging over our lives from day to day. This is the role of the law. But only the Good News coming into this valley can dispel the fog, let the sunshine pour down, and raise the crops.

Hybels: Negative persuasion only succeeds in moving the issue from the back burner to the front burner. If you never talk about death, hell, or judgment, it’s too easy for people to yawn and leave. But when you talk about them in the way Jesus and the others in Scripture did, people say, That’s right. I can’t ignore these truths forever. Someday they’re going to catch up to me. I’m going to have to make a decision.

Now you’ve got things on the front burner—and it’s time to rely on the gospel.

Some of these negative aspects have been forgotten in contemporary preaching because we don’t want to be the bearers of bad news. We want to make people feel good.

Hoffmann: People are making hell on earth for themselves right now. Not that this substitutes for the real hell, but this too is happening. We simply help people put their noses on it.

Leadership: Are either of you less or more intense now than in your earlier preaching? If we listened to an early tape of yours and a tape now, would you be more driving, or have you mellowed out?

Hybels: I better not be mellowing out yet!

I feel the truth on a much deeper level than I did earlier in my ministry. I think our people would say I’m more animated and authoritative in my declaration. But I think they would also say I’m more tender in handling difficult passages or situations of life, more patient with people who are struggling to come to know the truth.

Let’s say ten years ago I had been given an Oldsmobile. If I had driven it three years with no trouble, and someone asked me how I liked it, I would have said, “I like it. It’s served me well for three years.”

But, if at the six-year point I’d still had no major repairs and it was running great, I would say, “This thing has really served me well!”

Now I’m approaching the ten-year mark. If the car were still running fine, I’d be willing to do a television commercial and say, “Buy Oldsmobile!”

That’s sort of what’s happening in my walk with the Lord. The more of life I experience, the more trials I get through, the more strongly I say, “You know what? God can really be trusted.” Each passing year adds a little more gusto to my declaration.

Hoffmann: I haven’t been too conscious about style. Some of my friends and classmates once told me I was getting freer in my preaching, but I wasn’t conscious of it myself.

I believe it’s important for us to be more interested in the people to whom we’re talking than in how it we’re saying it. The point is to get the gospel across to them. And that grows on you as time goes by.

Hybels: Sometimes I pray, “Lord, if you want to embarrass me—if losing my place would cause the people to see me on a more human plane—however you can intervene in this situation to feed these people and bring glory to yourself, just do it.”

Hoffmann: It’s important to say things in a gospel way, with a smile, and short! The gospel can be preached as if it were a new law; that gives people the wrong impression. You’re standing up there with the authority of God to give them a great and wonderful offer. You shouldn’t come with a long face to do that.

This doesn’t mean you withhold from them the disaster that comes when you follow your own way in this world of ours. But you’ve got to get across that there is another way, and that He is the way, the truth, and the life. You say it with all the geniality that characterized Jesus Christ. He wasn’t sourfaced. People had a good time with him.

Leadership: What techniques have you found helpful in communicating that kind of good-news spirit?

Hoffmann: Again, I’m not too conscious of technique. I just want to understand and imitate the person of Christ.

I know a lot of Christians who claim to follow him, but they don’t admire him. Preachers have to admire him, want to be like him. We can never reach his stature, but we’re on the way.

I mean, the ministry becomes most persuasive when it is completely overwhelmed with the grace and glory of Christ. “What we preach is not ourselves, but Jesus Christ as Lord, with ourselves as your servants for Jesus’ sake. For it is God who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ who has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Christ” [2 Cor. 4:5–6]. He’s the one. That’s all we have to say to the world.

Leadership: What approaches are most effective in doing that? For example, is a congregation more persuaded by “fire in the pulpit” or a matter-of-fact approach? Would Billy Sunday or Tom Brokaw be more persuasive to your listeners?

Hybels: I think in various parts of the United States there are definite stylistic preferences. In New England, a somewhat more intellectual approach seems to go well. In the South it seems that if you don’t work up a sweat, people don’t feel like they’ve been to church. The West Coast seems slightly more razzle-dazzle; perhaps it’s affected by the celebrity culture. Here in the Midwest, audiences seem to be looking for the practical—“it had better work, show me, prove it, be straight with me, help me apply it.”

But God can use any minister’s style if the person is committed to Christ and committed to the Scriptures. I’ve noticed three or four flourishing ministries in the same community, led by people of vastly different temperaments, personalities, and styles.

Leadership: What if you find yourself pastoring a church where the core wants fire in the pulpit, and that’s not your personal strength? Or you feel the non-Christian culture doesn’t really respond to that anymore?

Hybels: The pastor and the core, as you call it, need to hammer out their objectives as a church. Do they exist mainly to please the saints? Or can the core realize that nonchurched people in many communities (and Chicago-Barrington is for sure one of them) do not respond well to hard-sell fire and brimstone. That’s not who Barrington people are. I would be foolish not to take that into consideration as I preach. But God can use different people in different places. The more I’ve traveled in recent years, the more I’ve appreciated that. It’s a tribute to his sovereignty.

Hoffmann: And his grace.

Hybels: And sometimes his sense of humor.

Hoffmann: People talk about the way Billy Sunday used to break up a chair in the midst of his sermon about alcohol—let me tell you, every gesture of the man was genuine and appropriate to the occasion. It was not just an act he put on.

I’ve talked to people who saw him, and they say his actions were absolutely called for by the situation. Nobody even noticed he was breaking up the chair. We can criticize Billy Sunday here today, but I’ve spoken to people who loved that man.

Leadership: How much do you think television and advertising have affected the way people listen to sermons?

Hybels: I think people today are almost numb. They are bombarded by persuasive advertising campaigns, and after a while they learn how to put up defenses, to say to themselves, I’m not going to let this get to me. No, I don’t need that dish detergent. No, I don’t have to get a weed whacker.

The trouble is, people are becoming adept at doing the same thing when they hear truth. They say, Here’s something else I don’t want to get into right now.

Leadership: They learn to taste but not to swallow.

Hybels: Yes—that’s a tremendous analogy. Paul spoke about people who learn but never come to the knowledge of the truth; they understand the intellectual aspects but never find the power.

Do you realize how many people are peddling their wares these days? We ministers refuse to view ourselves as peddlers—but we get lumped in with Fuller Brush and other persuaders just the same.

I meet once a month with a very intelligent, honest man who is diligently seeking the truth. He has already gone through the Eastern religions; now he’s checking out Christianity. At our last meeting, his closing words were “As I have examined different systems, I have always been able to find the proponent’s angle. I’ve been in your church for a while now, and I’m still trying to discover what your angle is. What’s in it for you? Next month when we meet, let’s talk about that.”

Suddenly it dawned on me: He sees me in a class with all the other peddlers in the world!

Leadership: What are you going to tell him next month?

Hybels: I’m going to say, “I’m a proponent of the gospel because I’ve been called to it. The truth has affected my own life, and I cannot keep silent about it.” I intend to tell him what I often say from my own pulpit: “I am not declaring the gospel so you’ll join this church. In fact, if a church closer to where you live teaches and preaches the gospel, go there. If you can grow under the leadership of another pastor, do it. Nothing is as important to me as your coming to Christ and your growing as a Christian.”

Leadership: How do you respond to the modern attitude that says, “In 1985 it’s all right to hawk your product, be it BMWs or weed whackers, but don’t try your ideas. This is a pluralistic society. Everybody’s entitled to his own opinion. You can try my pocketbook but not my head.”

Hoffmann: That’s a ruse. Industry is promoting both all the time. Ford Motor Company advertises not only its cars but also itself as an institution, and nobody objects to that. They even use different advertising firms, one to handle the idea and another to handle the product.

Sure, hype is omnipresent on the modern scene. But that’s part of life. The trouble is, people take everything to be hype, which confuses life tremendously. And religion is affected by it.

Leadership: Can you think of a time when somebody accused you of being a hype agent, a huckster, a peddler?

Hybels: Accuse? More often the Christian community collaborates in the hype. I get very uneasy listening to the way I’m introduced in various places I speak. People seem to need to boast about the “great personage” they’ve brought to their ministry….

Hoffmann: Well, you can deflate them in the first two sentences.

Hybels: I usually do—I sink the ship right out of the harbor! Sometimes right at the dock.

Leadership: Do you ever feel your ability to persuade is compromised by the fact you’re being paid to say what you’re saying? After all, there’s a living to be made in preaching. How do you let people know you really hold a conviction inside?

Hybels: That’s easy for me, because I was in business before I went into ministry. People believe me when I say that if I really wanted to make a good living, I wouldn’t be here. You can make money in the pastorate, but you can make a lot more elsewhere.

However, I must admit being troubled the more outside speaking I accept. I’m flown to a city, all expenses paid; I’m picked up in a nice vehicle and taken to a Marriott or Hilton or Hyatt. They ask me to speak two or three times, and pay me $500 or $750. They pay for all my meals. They give flowery introductions, treat me like a king, and then put me back on the plane for home.

What does this do to a person who used to view himself as a servant? You’re no servant on that kind of trip; you’re a celebrity. The more places you go, the more they advertise your books … and sooner or later, the system corrupts the servant, in my view.

I’ve had some very frank discussion about this with my staff and elders this past year. For the first time I’ve begun to see why certain pastors go on the road as much as they do. You can make a handsome living out there, you go to exciting places, and more people hear about your ministry and invite you to more places and buy more of your books and tapes.

Leadership: And there are no ornery elders out there.

Hybels: Hey, it’s nice. Everybody says you’re great.

But where is it all headed? What are we doing to good people?

Leadership: How do you cope with that, Dr. Hoffmann? You do a fair amount of traveling and speaking.

Hoffmann: Yes, but I work for a group of laymen—the Lutheran Laymen’s League. And it’s the business of laymen in this world to keep pastors humble.

People know I live on a pastor’s salary and make less than many church officials. That has a curious effect on contributions to our radio program, by the way. People are more willing to give.

Leadership: How do you know when you’re starting to lose the servant attitude? What are some of the warning flags?

Hoffmann: When you realize you’re not the same in private as you are in public. I remember long ago, during World War II, having dinner in a little restaurant in White Plains, New York, just before a benefit concert to sell war bonds. At the next table were Milton Berle, Ann Sheridan, Leonard Bernstein—a young man about twenty-one at the time—and some other entertainers.

I watched them, of course. They were famous. But do you know there was not one bit of laughter at that table the entire meal before they went on stage? Nobody said anything funny. Nobody was joyful. It was the gloomiest, most sodden occasion you could imagine. That’s show biz.

And I have a hunch a lot of pastors live a sham life, too. They’re pious and holy in public, but there’s little love at home. I’m currently aware of a pastor who has just been confronted with his affair with a member of the congregation. He has even admitted it—but he wants to stay on as pastor! That’s what makes people say, “This is just a big show.”

Leadership: What have you learned about persuading people to do more than taste the truth? What brings them beyond familiarity to commitment?

Hybels: The application, which is often missing. But I readily add that it’s also one of the most difficult parts of preaching. Most of us struggle with how to be articulate when it comes to guiding listeners to express their commitment.

A seminary prof told me, “All the way through your message preparation, keep repeating these two words: So what? So what? So what?” That has been a great help to me.

Jesus, you know, would tell stories and then say at the end, “Now, just go do that. When you find a neighbor in need, do what this guy did.” We sometimes wish he hadn’t been so specific, because it pains us to know we’re not doing it.

Leadership: So modern people are often not persuaded because they’re unsure what to do?

Hybels: Yes. They understand they ought to be more committed to Christ and the kingdom, but how?

Hoffmann: Even the most doctrinal sections of the Bible have a practical purpose. The section on Holy Communion in 1 Corinthians 11, for instance, includes “Let a man examine himself” and “Remember what this is all about.” Martin Luther’s Small Catechism, which is his book of instruction, never once uses either the word justification or sanctification—and yet they’re on every page. He used ordinary words and images that people could understand.

Hybels: Sometimes when I’m preparing a sermon, I stop and ask myself, “Should this be a frontal assault? A side-door sneak attack? Or am I going to come all the way around the back and just warm them up, so that a couple weeks from now I can hit them from the front?” In certain messages, all I’m trying to do is set the framework, get people thinking along a certain line. I don’t intend to bring closure. That will come three weeks from now.

Leadership: Give us an example.

Hybels: I did a series entitled “The Benefits of Brotherhood.” My ultimate objective was to get as many of our people as possible into small groups, because that’s where truth is applied and the microcosm of the church is lived out. But I didn’t stand up the first week and say, “All of you should be doing this, and you’re not.” That would have been a frontal assault.

The first week I simply said, “Throughout the centuries, if someone asked you, ‘What can I do to grow in the Lord?’ the answer would have been simple: ‘Study the Bible and pray.’ Those are indeed the two great means by which we can acquire spiritual maturity. But Scripture also plainly teaches another means—fellowship, whereby the Holy Spirit uses brothers and sisters to help us become accountable for applying the truth, for encouragement, rebuke, and other things as well.”

The second week I highlighted all the benefits of fellowship.

Week three was “Let’s say you want to be involved in a fellowship situation. How do you get your big toe in the water? What are the steps?”

Week four was “I can’t believe you wouldn’t want to do this.” Closure!

A lot of preachers, unfortunately, start at week four. It’s very easy to launch frontal assaults every single week—“God said it. Obey it or else!” But we don’t manage the staff that way. I don’t treat my children that way. When my kid wants to ride his bike in the street, I don’t say, “I’m your dad, and I’m ordering you not to ride your bike in the street!”

Instead, he and I go sit on the curb together. I wait till a big truck goes by, and then I say, “Now, Todd, if you were riding your bike in the street right now and that big truck hit your bike with you on it, what would happen?”

He says, “Oh, that would be awful.”

And I say, “You’re right. You would feel so awful. Mommy and Daddy would feel so awful, too. So now you understand why we don’t want you doing that. It’s because all you have to do is turn your head for a minute, and bang!”

“Thanks, Dad. I won’t ride my bike in the street.”

In the same way, I try to show people that God doesn’t rule capriciously. He doesn’t create legislation simply to inflict his sovereignty on his creation. He’s thoughtful and he’s wise.”

Hoffmann: Take forgiveness. It means nothing to the fellow who doesn’t need forgiveness and millions of good religious people think they don’t, you know. They’re busy repenting of the sins of other people all the time.

Well, if we’re going to preach practically, we bring that home to them. We open the door to confessing our sins.

This doesn’t mean we blast ‘em. Encouraging people is still the best way to achieve results.

Hybels: I heard someone say that persuasion is turning the valve an inch at a time . . . just turning, turning until finally the valve is closed (or open, whichever you’re working to accomplish). What we often want to do is turn it all at once.

People don’t get persuaded that way. I certainly don’t. I can list for you on one hand the times my whole world view was changed in a single conversation. It just doesn’t happen very often.

Politically speaking, I used to be sort of a hawk. You know, if some little banana republic gives us grief—boom! Take care of them. But slowly, over time I kept reading and studying and hearing a persuasive speaker or two talk about nonviolence from a biblical perspective, and I began to understand the heart of Jesus and—I’m almost a dove now. No person in one forty-five-minute lecture could have brought me the whole way.

Why can’t we grant our listeners the same dignity and say, “You don’t have to go the whole route today. All I ask is that you keep seeking truth. I’m going to be here every week; you just keep listening.” Turn the valve an inch at a time, and when closure comes, we’ll have people on the march for kingdom advancement because they’ve thought it through.

Hoffmann: Paul wrote to the Colossians at one point to be prepared “so that you may know how you ought to answer every one” [4:6]. Every person deserves an answer tailored to his or her own particular needs, not just a stock answer or the repetition of a formula.

On Sunday morning, of course, you have a bunch of people together at one time, but they still come to Christ individually. This is one reason we have to do our work outside the pulpit as well as in it.

Hybels: And if an unbeliever is coming to my church, listening to the gospel, the top question on his agenda is probably not “Do I want to believe the way this preacher believes?” Instead, in the midst of my thousands of words week after week, what he’s really asking is, “Do I want to become who this person is? People aren’t so concerned about adopting my belief system. They look at me and say, “Would I like those qualities in my life?” The sermon is in some ways an excuse to give us time in front of people to be checked out. They don’t buy oratorical skills. They buy life.

A pastor who’s not a great orator but is a good person, who loves the Lord and emanates the unmistakable qualities of a transformed life week after week, can stumble, trip up on illustrations, and everything: it doesn’t matter. People will say, “You know, I still want to be like that person.”