I should probably state up front that I neither “liked” nor particularly enjoyed Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, which had its American premiere at the 2015 SXSW Film Festival.

Universal Pictures International

Universal Pictures InternationalIt is a lush, hypnotic, immersive film experience, so I can say that I admired its artistry. But when co-star Domnhall Gleeson told the audience that he got irritated watching his character on screen, I smiled. He wasn’t the only one.

Gleeson plays Caleb, a programmer who wins a week’s visit with Nathan (Oscar Isaac), the reclusive genius who owns the company where Caleb works. After a helicopter ride over glaciers and forest, he lands at a laboratory/residence that looks sort of like a Bond villain’s lair as designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Gushing enthusiasm quickly gives way to suspicion when Nathan requires Caleb to sign a non-disclosure agreement. What can’t he disclose? Anything. Who can’t he disclose it to? Anyone.

Caleb also gets a key card that only opens certain doors and doesn’t operate any of the telephones. Apparently he has never seen a horror movie.

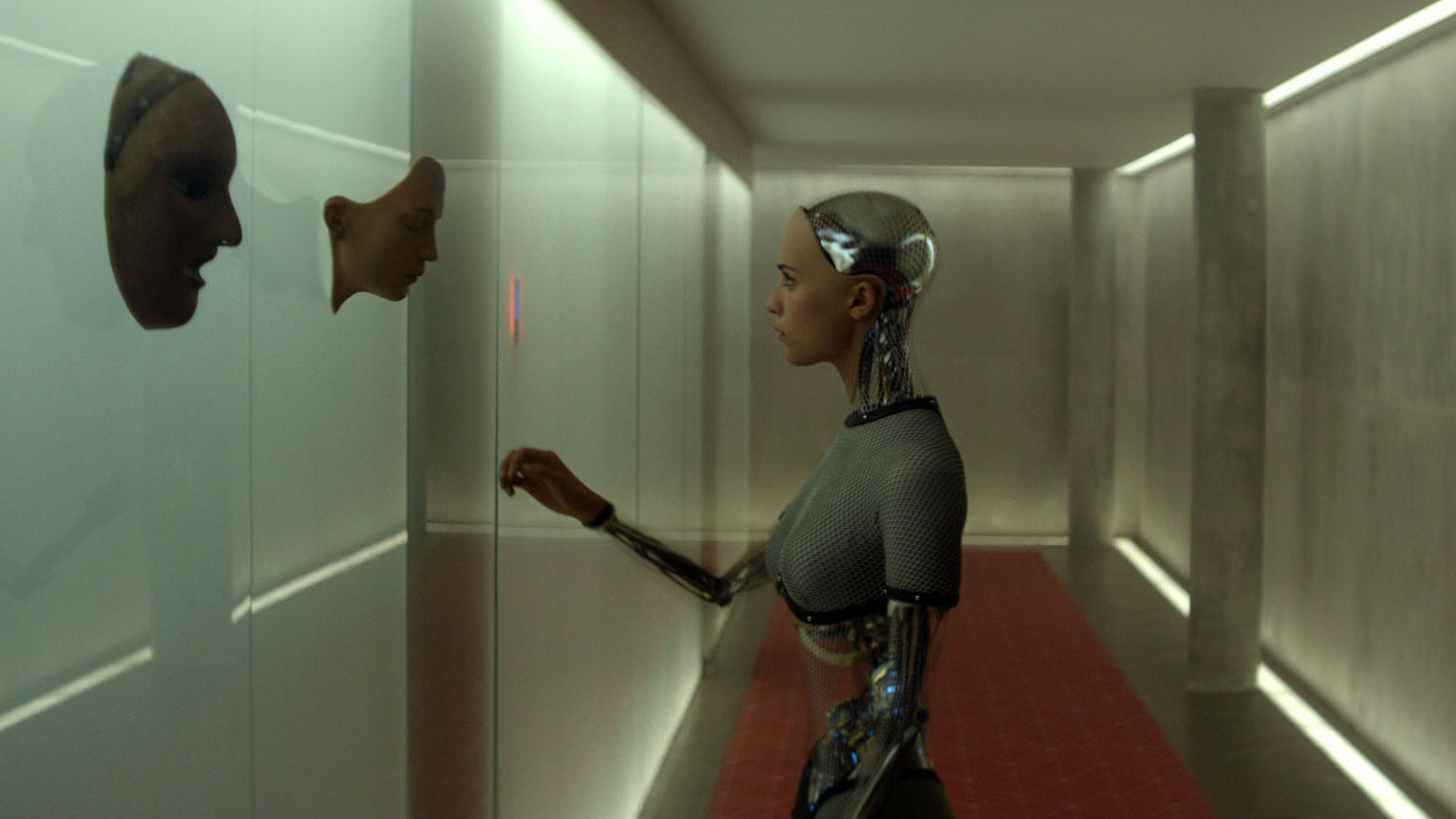

It turns out that Nathan’s big project has been working on artificial intelligence. Caleb has been selected to administer a “Turing test” on Ava (Alicia Vikander), a robot with a covered torso, bare midriff, and wires visible beneath her arms and legs. Caleb rightfully protests that a Turing test is supposed to be about whether or not an artificial intelligence can pass for human and Ava has already been revealed as a robot. Nathan says the real test is whether Caleb will accept her as real even if he knows she is artificial.

At the film’s premiere, Garland told the audience that he both questions and disagrees with Americans’ veneration of movie directors. He considers himself a writer first, even though he took the helm for Ex Machina. While his direction of the film is more than adequate, the words (as Isaac told the audience during a Q&A session) are the real star of the show. There are ideas aplenty in the film, and the architecture visually reinforces the merging of the natural world and the artificial constructions that inhabit it. And yes, the “sessions” Caleb has with Ava are well acted and fun to watch. But a good foundation for an academic research paper is a different thing than a solid idea for a science-fiction film.

Universal Pictures International

Universal Pictures InternationalNathan exudes menace, Caleb flirts with Ava, and pretty soon a silent Asian woman named Kyoko is introduced. Power fluctuations in the building temporarily suspend the surveillance video—or do they? In fleeting moments of privacy Ava pleads with Caleb to help her. Is she playing him, or is this part of the set up that Nathan has scripted to convince Caleb it is real? Does Ava really like Caleb or is she just pretending? Does Caleb really like Ava or is he simply fascinated by her? And if he doesn’t know his own feelings, how can he be sure he is human?

There are two weaknesses to Ex Machina, and one of them is in this middle act. Between the setup and the resolution, Caleb and Nathan have so many feints and counter-feints that I more or less stopped caring. Other than Sleuth or The Sting, has any film had this many suggestions that everything is an elaborate façade and not degenerated into farce?

Yes—that structure reinforces the content’s themes in a way that is clever: we, like Caleb, are trying to figure out if we are being scammed. But unlike Caleb, we know nothing we can do will affect the outcome, so we are left simply to wait for him to figure things out . . . or not.

Universal Pictures International

Universal Pictures InternationalWhen the last act finally kicks into gear, the revelations involve a lot of nudity and violence against women. Here, too, the form is appropriate to the subject matter. Ava’s experience becomes a striking metaphor for a woman’s oppression in a severely patriarchal system. Still, as in Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, the violence and nudity get conflated in ways that struck me as ironically exploitative, given the films’ respective themes decrying the exploitation of women. I also thought the end went on about three minutes too long. There comes a point where, if we have been paying attention, we know what will happen once a character walks out a door.

Yet for all those complaints, Ex Machina is a rare breed: a science fiction film that is geared towards grown-ups and willing to take its own ideas seriously. Perhaps too seriously. All that philosophizing works fine in a science fiction story or novel, but even I, Robot had a conventional murder mystery to keep the audience engaged in between its object lessons on what makes us human.

Caveat Spectator

To be clear, the “graphic nudity” in the MPAA warning doesn’t exclusively refer to periods when Ava’s mechanical parts are showing. The film has several scenes with full frontal female nudity. The violence is moderate but as some of it is initiated by male characters towards (machines that are designed to look like) females, it is particularly disturbing. There are at least two stabbings and one act of self-mutilation (cutting). Caleb and Nathan both drink. Nathan appears drunk once and speaks of being drunk on other occasions. Use of profane and/or obscene epithets is moderate. The men discuss the possibility of having sexual intercourse with Ava using graphic euphemisms. There is a moderate amount of talk about evolution, and Nathan claims that sexual orientation is “assigned” to humans (presumably by God?) in a manner to similar to the way he has assigned sexual orientation to Ava. Most younger teens would probably opt out—it’s a very talky movie, but parents are cautioned, particularly if they idea of robots might tempt younger members to want to see it.

Kenneth R. Morefield (@kenmorefield) is an Associate Professor of English at Campbell University. He is the editor of Faith and Spirituality in Masters of World Cinema, Volumes I, II, & III, and the founder of 1More Film Blog.