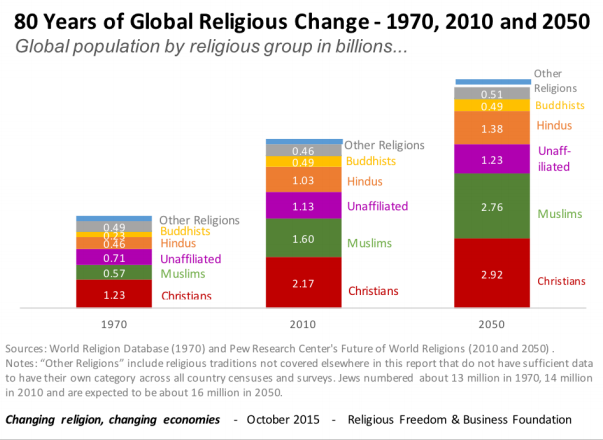

A deep dive into economic and demographic data suggests that not only is the world becoming dramatically more religious, but the resulting religious diversity is redistributing wealth like never before.

Today, the bulk of the world’s wealth resides in majority-Christian countries. But by 2050, the five leading economies are projected to be “one of the most religiously diverse groupings in recent memory,” say researchers Brian Grim and Phillip Connor at the Religious Freedom and Business Foundation (RFBF).

The foundation’s latest report, which compares the “best available demographic and economic data,” predicts that, come 2050, only one of the top five economies—the United States—will be a majority-Christian nation. “The other mega economies in 2050 are projected to include a country with a Hindu majority (India), a Muslim majority (Indonesia), and two with exceptionally high levels of religious diversity (China and Japan).”

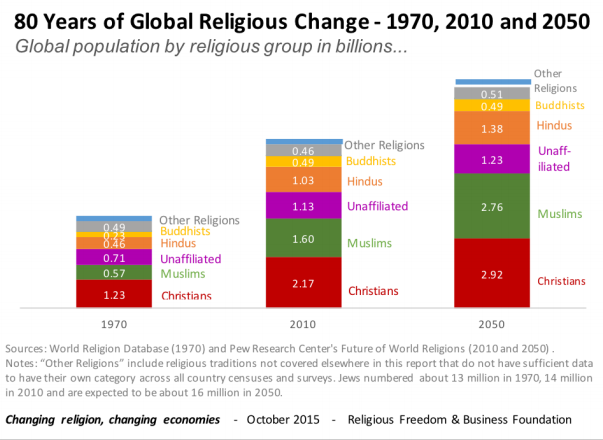

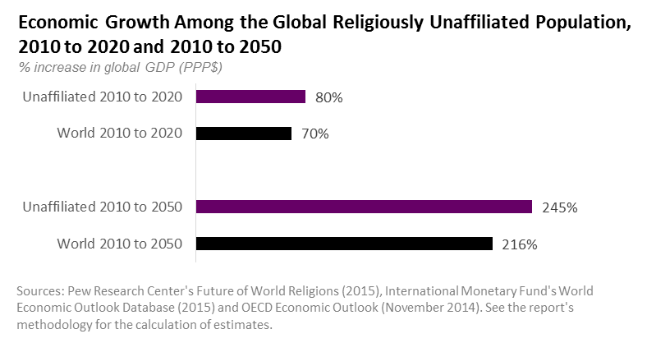

Additionally, while religious “nones” continue to grow in raw numbers, their share of the global population actually peaked in the 1970s. “Religious populations are projected to outgrow religiously unaffiliated populations worldwide by a factor of 23 between 2010 and 2050,” states the report. “This will increase religious diversity and alter the distribution of wealth.”

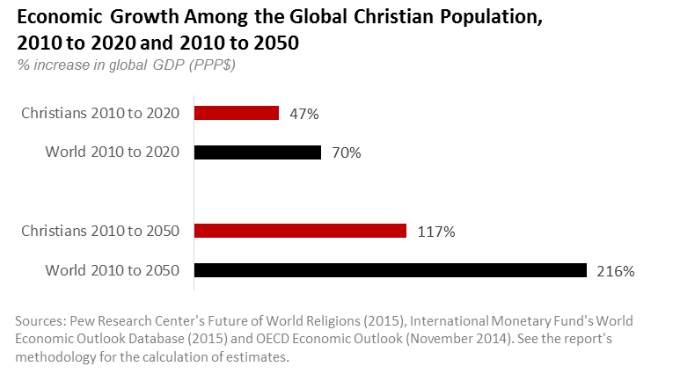

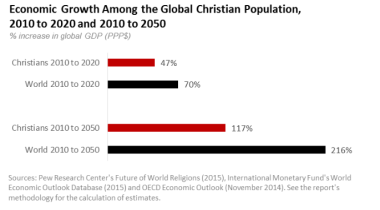

While global GDP is expected to increase by 216 percent from 2010 to 2050, growth among Christian populations is only expected to increase by 117 percent. Christians make up 31 percent of the world’s population, according to the most recent data available, and are expected to maintain this percentage by 2050. (Currently, there are 2.2 billion Christians in the world, a number which is expected to hit 2.9 million by 2050.)

One reason the growth of majority-Christian nations isn’t expected to shoot up: most already have well-developed economies, said Grim.

They could grow more quickly if “they began at a lower starting point,” Grim told CT. “Additionally, much of the Christian growth in the next decades will be in Africa, from primarily demographic growth, though also some conversion. [By 2050], about half of Christians will live in sub-Saharan Africa. While those economies are beginning at a lower point, they aren’t expected by economic forecasters to grow as fast as the economies in Asia.”

The study coupled religious demographic data from the Pew Research Center with GDP data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and weighted them by income differentials to find the projected GDP of each religious group.

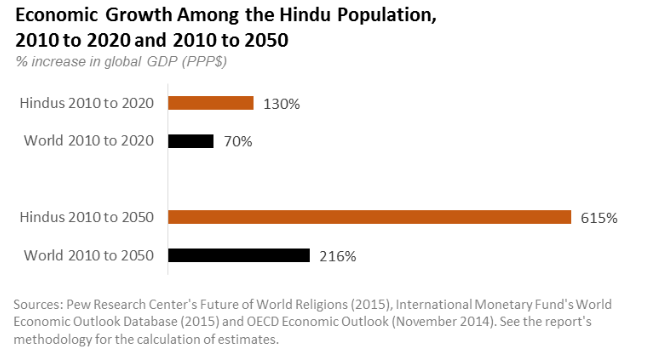

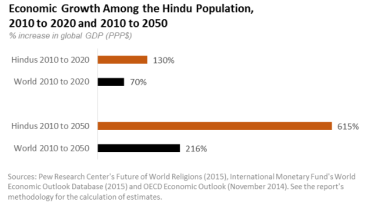

The religious population with the highest anticipated GDP growth by 2050 (615%) will be Hindu, the report said. Mostly concentrated in India, the population is expected to increase by 400 million. The Hindu share of the world’s population is expected to stay nearly constant (13% to 15%) over the next 35 years.

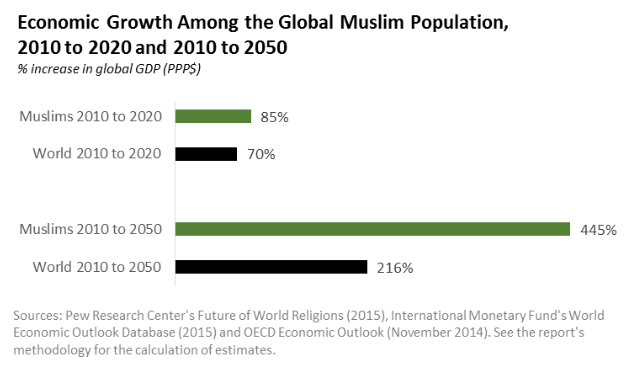

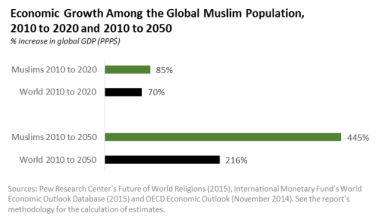

The GDP of the Muslim population is predicted to increase by 445 percent by 2050. At the same time, the number of Muslims is expected to grow from about 23 percent of the world’s population to nearly 30 percent.

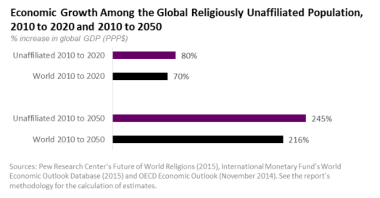

Religiously unaffiliated economic growth is predicted at 245 percent, much of it occurring in the Asia-Pacific region, specifically China. Today, this population makes up 16 percent of the world’s population, but is expected to fall to 13 percent by 2050.

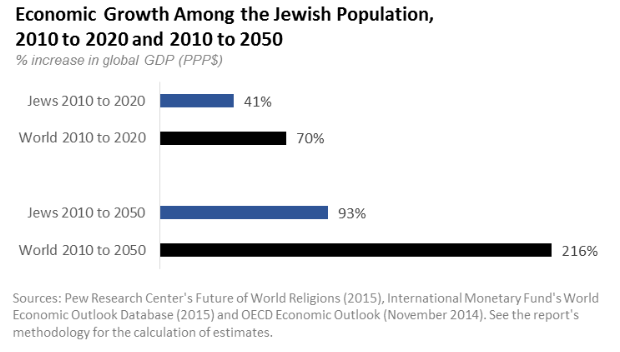

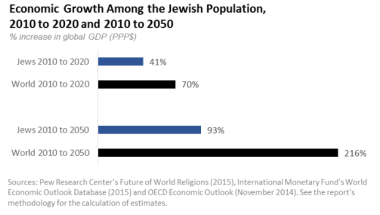

Other than Christians, Jews are the only religious group highlighted by the report with growth lower (93%) than the expected global GDP increase. Jews make up 0.2 percent of the world’s population and are expected to compose the same percentage of the world’s population in 2050.

A growing economy does not necessarily mean the religion that is most prevalent in that country will grow, says Grim.

“There is no clear relationship between the two,” he said. ”Where you have advanced economies, there has been a trend towards less religious affiliation, especially in Western Europe…. People have more freedom to opt in or opt out [of religion]."

At the same time, the economic growth in China has been accompanied by a surge in religious practice, ranging from folk religion to Christianity to Confucianism, he said.

As economies develop, people transition from labor intensive agricultural and production jobs into more service positions, says Grim. Male and female education rates increase, which tends to delay marriages and ultimately lower birth rates.

With the exception of Buddhism, which has already largely plateaued because of the birth rates in China, the growth rates of all faith groups are slowing, said Grim. “Even the expected rapid growth of the Muslim population is still a slowing trend.”

Previous CT economic coverage examines a new model of Christian stewardship that’s scalable, global, and can compete with China; how countries which had a significant missionary presence in the past are on average more economically developed today; and why the government is the best institution to change the poor’s standard of living—though Christians reduce poverty too. CT also covered the 10 most popular strategies for helping the poor.