Last January, I was in a room full of movie lovers who were discussing the movies they'd seen the previous day at the Sundance Film Festival, and one of them had seen Equity. He recounted how he'd liked the movie, but had been thrown off by the mostly-female cast, finding himself wondering why most of the main characters were women: the high-powered investment banker, her ambitious VP, the lawyer investigating them, the hacker.

I wondered, why did they have to be women? he said. And then I thought: oh, this is how women feel watching these movies.

Sony Pictures Classics

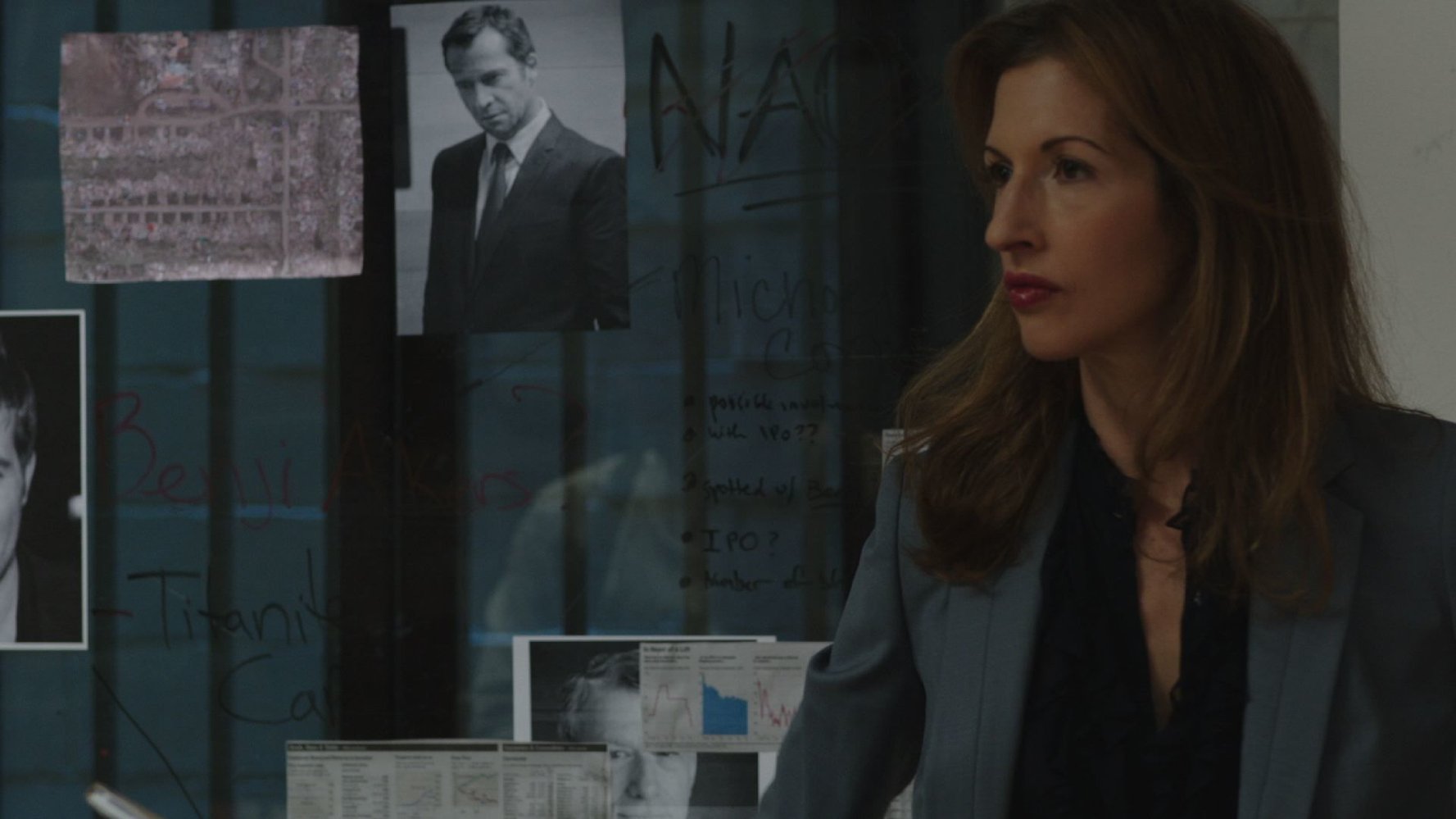

Sony Pictures ClassicsIndeed. In Equity, investment banker Naomi Bishop (Anna Gunn) specializes in taking companies public, but her last IPO tanked after the owner complained that she “rubbed them the wrong way.” Now she's vying to land another: a security-conscious social networking company whom she helped find their initial venture capital investors. She and her VP Erin Manning (Sarah Megan Thomas) land the deal and start lining up investors.

Meanwhile, at a networking event, Naomi bumps into her old friend Samantha (Alysia Reiner), a lawyer who investigates securities fraud. But maybe the happenstance meeting wasn't accidental; Naomi's ongoing liaison with her colleague Michael Connor (James Purefoy) is cause for suspicion.

Equity is an intelligent film for smart people, or at least those who aren’t afraid of some finance wonk talk and terms like “end-to-end encryption.” Instead of succumbing to the trope-y sleek glamour of many of its Wall Street predecessors, the movie gets that finance is a grueling matter conducted largely by tired, determined people under fluorescent lights who mostly just like the adrenaline and satisfaction of the work. And the paycheck doesn’t hurt.

It is hard to parse exactly what to say about the politics of a film like Equity, which obviously has gender on its mind. On the one hand, just recounting the plot without gendered pronouns is a bit like that old riddle in which a man and his son are in car crash, and while the man dies at the scene, the son is rushed to the hospital, where the surgeon declares, “I can't operate on this boy—he's my son!” It's only a riddle in a world in which the default gender of a surgeon is male, which is hardly the case any more (try out the riddle on your local Millennial and see what happens).

Sony Pictures Classics

Sony Pictures ClassicsSimilarly, Equity's strongest statements about women's abilities (and disadvantages) in the workplace come from the ways it shows the viewer, instead of just telling them, that it can be tough to be a professional woman, but that it's also possible. It's obviously taking its cues from cultural discussions of the sort found in Anne-Marie Slaughter's 2012 Atlantic article “Why Women Still Can't Have It All,” which even makes an appearance on a character's Blackberry (Sheryl Sandberg is nowhere to be seen, which is surprising until you realize the film is set in 2012).

And the film does pull this off in myriad ways, quietly raising issues around pregnancy and motherhood, sexual harassment, and the challenges of being taken seriously through plot. Ethical complexities mostly surface in characters’ facial expressions, not their conversations. The film’s glass ceiling is felt, more than talked about. That's far more effective than having characters deliver monologues about those same topics. And while most of the bad guys are male, that’s realistic: most of Wall Street (and Silicon Valley, for that matte) is male, and it’s no stretch, given how fraud tends to blossom in the testosterone-fueled macho culture of high finance. (Wolf of Wall Street, many Wall Street people will tell you, is perhaps too measured in its depiction of that world.)

Equity is a calm film, in the way that makes you nervous because you know there's something ready to explode beneath the surface—in some ways it reminds me of Margin Call. Its ending is tricky and messy. And with a strong cast—especially Anna Gunn, whose steady, steely performance anchors the film—it often succeeds at what it's doing.

Sony Pictures Classics

Sony Pictures ClassicsUnfortunately it veers off into preaching a couple times in ways that feel more awkwardly tacked-on than pertinent to the story itself, including a speech near the end that unfortunately lingers in memory. And I found myself distracted by the camera repeatedly: if you're going to make your camera evident to the viewer, there should be a good reason that adds to the film as a whole. But instead, Equity's camera seems to constantly be trying cool stuff out without a coherent sense of why—zooms here, overhead shots there, sometimes a handheld shot, occasionally shot/reverse shot conversations with strange amounts of empty space behind the characters' heads. When coupled with occasional odd editing choices, that sort of filmmaking leaves something to be desired.

But Equity is only director Meera Menon's second feature, and it shows a clear sign of vision as well as a nose for what works. It's a compelling story—about finance, regulations, and data, no less—that, if it unsettles the viewer, is for all the right reasons. And who knows? Maybe some day it won't feel like a riddle anymore.

Caveat Spectator

Profanities and sexual discussion and content; several couples are seen in bed together (one heterosexual couple, one lesbian couple, no nudity). Of greater importance: the story hinges (and returns) to a speech about how great it is that we can talk about liking and wanting money, and several characters make unscrupulous and ethically questionable decisions for which they are not necessarily punished by the film, so it’s worth flagging and returning to those for discussion afterward.

Alissa Wilkinson is Christianity Today's critic at large and Associate Professor of English and Humanities at The King's College in New York City. She is co-author, with Robert Joustra, of How to Survive the Apocalypse: Zombies, Cylons, Faith, and Politics at the End of the World (Eerdmans). She tweets @alissamarie.