Some of my earliest memories are connected with church: the sounds and smells and distinctive aura of this place that was more than a place, and its central role in our lives. When I was a boy in California in the 1950s, growing up with my mother, my grandma, and my younger brother (my parents were divorced when I was five years old), we went mostly to Baptist churches (three times a week in the early years). So it was until I started college in the fall of 1966 (by then I was inwardly detached, only to return to my faith a bit later).

One important feature of that world was "testimony." Your testimony was a public account of how you became a Christian. Over the years I heard countless people "give" their testimonies—often people in the churches we attended, other times visiting speakers (perhaps at the "revivals" that tended to be scheduled once a year, usually in the summer and usually lasting for precisely one week, though sometimes two). Especially if given by visiting speakers, testimonies could include dramatic episodes of sin and misery leading up to the moment of conversion; they might also (though not routinely) involve accounts of miracles.

As I grew older, I felt increasingly ambivalent about this practice. I was often deeply moved by these accounts—not only heard in person but encountered on the page. At the same time, testimonies were often formulaic, and sometimes they seemed to be exaggerated, distorted, untrue. (Parodies ran through my head sometimes, unbidden.) They shared the strengths and weaknesses of what I learned to call "autobiography" or "memoir" more generally. In fact, so I learned, the genre of autobiography owed much to the Christian tradition of testimony, as exemplified by Augustine's Confessions. I found that my experience in church came in handy when I was reading books like Patricia Caldwell's The Puritan Confession Narrative: The Beginnings of American Expression, or Carl Dawson's Prophets of the Past: Seven British Autobiographers, 1880-1914, or Joan Didion's Slouching Towards Bethlehem.

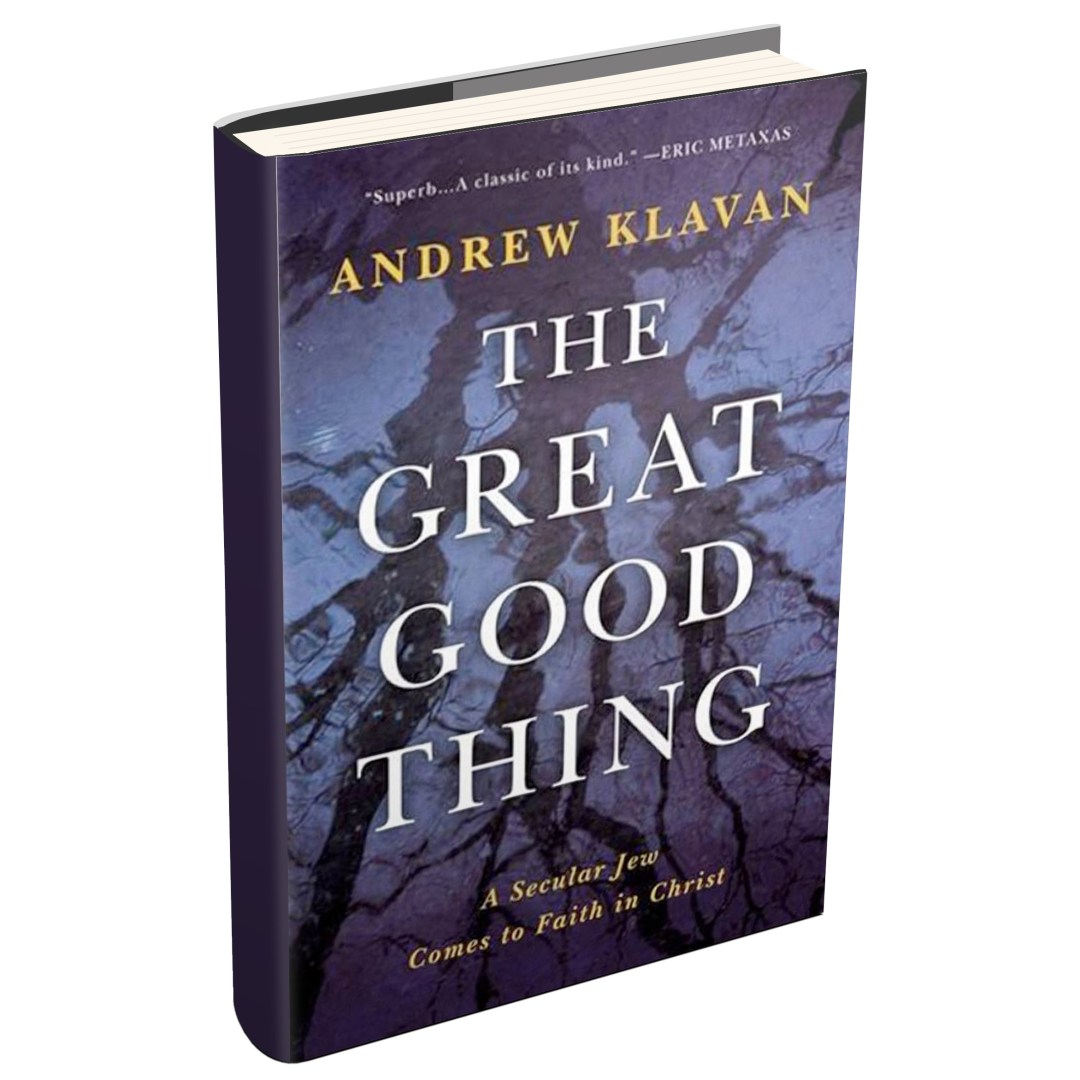

Those early memories of hearing "testimonies" came back to me strongly while I was reading Andrew Klavan's The Great Good Thing: A Secular Jew Comes to Faith in Christ, a work of testimony that begins in a church in New York. If you have been reading Books & Culture for any length of time, you know that Klavan is a writer I greatly admire. Stephen King has called him "the most original American novelist of suspense since Cornell Woolrich," and his most recent novel, Werewolf Cop, is (so I think) his best yet.

When I started reading Klavan about ten years ago, devouring his books, I had no idea that he had recently been baptized (nor did I know that he had grown up in a secular Jewish family). Gradually, as new books appeared, I began to think that this writer might be a Christian, until finally I was convinced that it must be so. The Great Good Thing tells the story of his conversion with candor, wit, and humility (no preening, no cant). It is a memoir, he emphasizes, focused on that story, not a full-fledged autobiography, but it encompasses the whole arc of his life, and especially his childhood and growing-up years before he left home at the age of seventeen. (In my favorite part of the book, he tells of meeting and pursuing his wife-to-be, Ellen, when he was a student at Berkeley.)

The setting in which Klavan grew up was in many respects wildly different from mine (and different yet again from yours, dear reader). While he and I share a number of passions (including an admiration for Raymond Chandler), we are VERY different. (For one thing, he could beat the crap out of me.) But, somewhat miraculously, I can read his story not as if across a great gulf, not as if examining an interesting specimen, but with a deep sense of kinship (and occasionally tears—that's probably another way we're different) and gratitude that we both have found (have been given) the Great Good Thing.

John Wilson the editor of Books & Culture.

Copyright © 2016 Books & Culture. Click for reprint information.