Caution, many spoilers ahead.

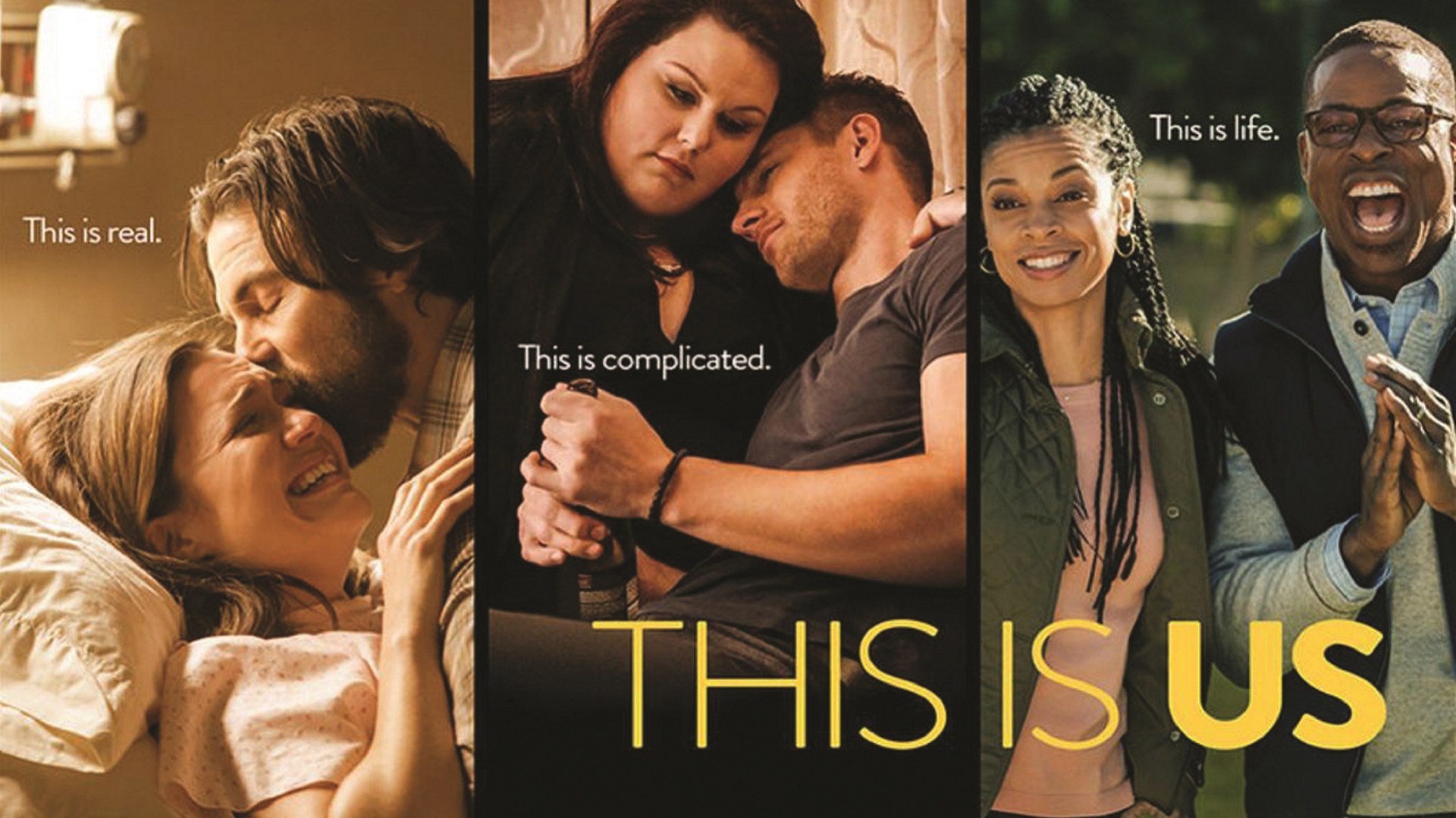

If you haven’t seen NBC’s smash hit show This Is Us, it’s likely that you’ve at least heard about it (and equally likely that the person who told you about it cried a little during the explanation). The emotionally-charged drama has captivated viewers nationwide, many of whom have reverted to the old-fashioned, pre-“binge-watching” habit of anticipating a new episode each week. America has fallen in love with This Is Us.

The show follows Jack Pearson, his wife, Rebecca, and their kids: Kevin, Kate, and adoptee Randall. In each episode, viewers see the beginnings of the Pearson family, learning about Jack and Rebecca’s early marriage and the kids’ childhoods. Simultaneously, viewers discover how the kids are handling life as young adults and what has happened to them and their parents 36 years after their births. The show has many strengths, but this subtle time-hopping element is one of its most charming features.

Last September’s pilot opened with the impending birth of the Pearsons’ triplets—an event that, I imagine, was part novelty, part nostalgia for many audience members. I doubt many viewers gave birth to triplets themselves in 1980, but those details feel irrelevant; if babies represent anything, it’s hope, and tripling the number of infants only raises the stakes of potential.

As Jack declares just before his babies are delivered, “I’m going to need everyone… to believe me when I say that only good things are going to happen today.” Whether or not you’ve brought a baby (or two, or three) into this world, there is a desperate resolve in his voice that rings true for all of us—for “only good things to happen” is, of course, what we all want, especially when confronted with the very real possibility that only terrible things could happen. The problem is, sometimes they do.

And things do go wrong for the Pearsons. Only two of the triplets survive into infancy. The third, Kyle, is lost—and while faithful fans of the show have already mentally interrupted me with reminders of the ultimate good that results from Kyle’s death, it’s important, if not necessary, to pause here. Kyle’s death is tragic; it is a lost life, and it forces a young couple into grief on a day that was expected to bring them only joy.

Kyle’s death also introduces a number of tensions that turn into vices for the characters—defects we discover in subsequent episodes. Kevin’s jealousy, Rebecca’s secrecy and dishonesty, Randall’s lost biological family and confusion about his identity—all of this pain begins with Kyle’s death. There are also problems that aren’t directly connected to the loss of the baby, but rather seem to materialize without direct causation: Jack’s alcoholism, Randall’s anxiety, Kate’s gluttony. Darkness, it would seem, creates more and more darkness.

This Is Us flirts with melodrama at times, but the show understands what it means to be fallen, to live in world in which horrible things are both intended and incidental. No characters are spared from suffering, and all of them carry the weight of their worst decisions. For instance, when Randall confronts Rebecca about the fact that she had contact with his biological father, her face twists under the agony of her own regret, and she desperately reaches out to her son for a reprieve, aching to give up the ghost that has haunted her for his entire life. Kevin and Randall, meanwhile, attempt to build a cordial sibling relationship, but their old rivalries immediately flare up. They find themselves arguing like children on the sidewalks of New York, and ultimately wrestling each other to the ground as onlookers film the spectacle. Jack, Kate, and Randall’s birth father, William, with varied success, fight their own monsters of addiction. There is no whitewashing of sins in This Is Us—evil comes with a vengeance, haunting every ordinary person.

This stark explanation of the characters’ struggles may make it seem like This Is Us is a bit of a downer. But the audience’s response to the show would suggest that quite the opposite is true: Viewers report feeling surprised, uplifted, and inspired by the story. How? What good can come from so much tragedy?

One answer may be that This Is Us happened upon a simple, important truth about redemption: It often takes time. Viewers are given the gift of time compression, of watching a narrative arc resolve itself in two different decades. We learn that Rebecca lies not out of carelessness or malice, but out of fear that the truth will rob her of her child for a second time. Randall works tirelessly and flawlessly because he has created a habit out of earning acceptance from an unforgiving world. Kevin fails his romantic interests because he is in love with the one woman who won’t love him back. These contexts soften us toward these characters. Time creates empathy and understanding, and, at times, fosters love.

In his first letter to the Corinthians, the Apostle Paul famously wrote about putting away childish things, about childish reasoning and adult understanding. This truth is illustrated powerfully in the narrative arc of This Is Us. The younger version of this family cannot be faulted for their youthful inexperience—but they should grow beyond that. The burdens these characters carry lead them to harbor tremendous vices—but at some point, the burdens have to be laid down.

Viewers are compelled to watch these characters not because they struggle, but because we want to see them overcome their difficulties. We want a happy ending to Randall’s adoption. We want Kate to lose the weight. We want Rebecca to tell the truth, for Kevin to love Randall like they are brothers, for Randall to show grace to his mother and himself. Though these victories may come slowly, in sentences and moments and small, small gestures, they are all valuable for being lights that permeate the darkness, tiny acts of rebellion against evil. The characters grow away from their reactionary transgressions. They become stronger, wiser, and more patient.

As audience members, meanwhile, we are afforded a gift that the Pearsons do not have: We can see the whole story of their lives in a handful of 40-minute episodes. We may be quick to ascribe the show’s unified storytelling to the convenient magic of television, but the truth is that our lives, too, can have incredible narrative direction. We only see our stories in minutes and hours, but as Christians, we can be certain that there is divine orchestration connecting each of our days to one another. We see, as Paul writes, through a glass darkly, but we have been promised that we will see face to face.

As he nears death, Randall’s father, William, is close to that kind of complete sight. As he reflects on his life, he is asked what it feels like to be dying. William responds, “It feels…like all these beautiful pieces of life are flying around me and I’m trying to catch them. When my granddaughter falls asleep in my lap, I try to catch the feeling of her breathing against me. When I make my son laugh, I try to catch the sound of him laughing—how it rolls up from his chest. … Catch the moments of your life.”

William, a former addict who has only spent a few short months with his biological son, could easily choose to be bitter and disappointed at the finale of his story. But his words are full of joy. Perhaps it is because he sees more clearly, having lived a whole life, finally able to see every event woven together.

On the day that his triplets were born, Jack told the doctor that only good things were going to happen. He looked at his panicked wife, squared his eyes in determination, and asked her to trust him, to know that the impeding moments of risk and fear would resolve well. She responded, “I love you. Yeah, I know it. I know it. ”

This moment could be interpreted as wishful thinking, the desperate attempt of a scared father to will his family into a happy ending—but ultimately, Jack does sees a truth that will stretch beyond the confines of his children’s birthday: Love demands trust. It requires faith beyond what we can see and measure, and confidence that, no matter how dire the circumstances, those who love us and whom we love will work together for good. The good things that happen to Jack are bigger than his hopes. His family will be more beautiful than he can dream. The ending may not what Jack and Rebecca would have predicted, but the faith and love they exhibit holds them up through the coming tragedy and into the beautiful redemption that follows.

Like Jack, we want only good things to happen today—and like Jack, that is precisely what will happen, when God gives us eyes to see.

Amanda Wortham is a writer at Christ and Pop Culture who also teaches literature to a fantastic group of teenagers at a classical Christian high school. She lives a little south of Birmingham with her husband, Ben, and their two splendid girls.