“What experience and history teach is this — that nations and governments have never learned anything from history, or acted upon any lessons they might have drawn from it.” —Georg Hegel

In the developed world, we have become accustomed to “high tech” being part of our lives. What would happen, however, if it became the whole of our lives? What might happen if this next phase of technology is not handled well? If I let my imagination run a little freely, this might be a near-future “top of the news” story:

As Americans woke and turned on their video walls to watch the news, the scenes from the previous night were of men in dark coveralls, attacking long distance semi- trailer trucks.

The target of their anger was a fleet of “robo-trucks” the latest commercial product from a revitalized American Motors. The trucks were owned by Transat –Trans American Stateline Automated Trucking Company, the first major automated trucking company operating in America. This exciting and low-cost technology, which allows autonomous hybrid hydrogen/electric-powered, high-capacity trucks to be controlled along the freeway by one operator in a central location, has rapidly transformed the transportation and logistics industries.

The President and Congress condemned the attacks as “techno terrorism,” but an anonymous video claiming credit for the attacks argues laborers displaced by robots have no recourse. The federal government has been looking into programs to create new kinds of jobs or offer a social wage to those displaced, but early estimates suggest it may be years before effective policies are in place.

This future scenario is, of course, fictitious, but it is also quite plausible given the pace and direction of technological advancement. For those who, like myself, live and work in Britain, there is an acute sense of déjà vu.

An age of change

In 18th- and 19th-century Britain there was social unrest. The Industrial Revolution had released a flood of new inventions that supplanted manual labour. James Hargreaves, a craftsman weaver and carpenter devised a “jenny,” probably a Lancashire dialect corruption of “engine,” which would allow one person to do the work of eight cotton spinners. Entrepreneur Richard Arkwright installed water-powered spinning machines in his mill, creating the first automated factory. This factory used low-skill, low-wage machine minders and displaced skilled spinners and weavers.

By the early 1800s, anger among the workers was growing, but any attempt to organize was blocked by a government ban on laboring organizations. Any who tried to organize were imprisoned.

At the same time religious and social change was happening as well. Under the preaching of John Wesley and George Whitefield, England had experienced revival. However by the early 1800s, only 20 years after Wesley’s death, some of the working class members of the church felt that Methodism was becoming as staid and middle class as the Church of England. Indeed, some of the more ornate chapels were built in a rich Georgian architectural style very similar to Anglican churches of the period.

One of the working men, Hugh Bourne, a wheelwright and part-time engineer, heard about the camp meetings in America and decided, despite local opposition, to hold a similar meeting. He was joined by William Clowes, a potter, and between them they began a productive outreach blessed with signs of the Spirit.

The group they founded became the Primitive Methodists and were called “Ranters” by their detractors. Their appeal was to the working man, and as they worked with them, they saw that the problem of poverty stemmed from exploitation by the owners of mills and factories. Also, through their attendance at Sabbath (Sunday) school, literacy levels among men and women in the chapels increased. This education enabled some of them to take the lead in agitating for better working conditions.

The Tory government of the time, alarmed at revolution in America and France, used local magistrates to clamp down on the fledgling movement, but still it grew, with small chapels opening throughout the North of England. The traditional Wesleyans, concerned at this fervor, withdrew the “preaching tickets”—formal endorsements from Methodist leadership—from Bourne and Clowes. The two also faced obstruction from local magistrates who opposed the open-air preaching. While the Primitive Methodist movement had a religious focus, it had social and political consequences.

Armed Resistance

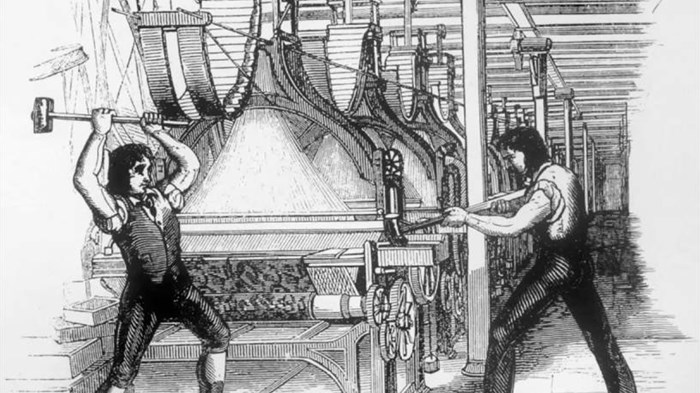

As mechanisation increased, groups of young men began to attack factories at night and destroy the machines. They used the name of a fictional local hero, Ned Ludd, and became known as “The Luddites.”

In 1812 these attacks took a more dangerous turn. William Cartwright, owner of Rawfolds Mill in Yorkshire, introduced new machinery that would weave and finish the wool cloth more cheaply than using the skills of the manual workforce.

One of his workmen, George Mellor, had served in the military, was better educated than many workers, and had natural gifts of leadership. Using his contacts with the local men at work and in the chapel, he began gathering a group of men and taking them into the hills to train and drill in what are now called insurgency tactics. The chapel meetings on Sunday and the Methodist Society mid-week meeting provided a cover for their clandestine gatherings.

William Cartwright heard of what was going on and wrote to Spencer Perceval, the prime minister, and Richard Ryder, the home secretary, and asked for help from the military. Perceval, an Anglican from the evangelical tradition, was sympathetic to reform but was a member of the aristocratic ruling elite and fearful of any kind of revolutionary movement.

On Perceval’s instruction, Ryder appointed General Peregrine Maitland, an experienced army commander, to hunt down the Luddites. Some weeks later, Mellor and his men attacked the Rawfolds Mill with muskets, under the cover of darkness. As they crossed Hartshead Moor, Anglican curate Patrick Brontë spotted the raiding party, but though he knew who they were, he took no action. Perhaps his own working class origins made him sympathetic to the men. His daughter, novelist Charlotte Brontë, later recounted how their father often told them the story.

Upon reaching the mill, Mellor and his men found Cartwright had been tipped off and the mill was heavily defended. Even under heavy gunfire, some of the Luddites reached the mill door but could not break in. Mellor and the remaining men fled, leaving two of their men dying on the open ground. These casualties were taken inside and interrogated by the militia, but neither of them gave anything away.

The fate of the Luddites

George Mellor went into hiding, deciding to attack and kill another mill owner, William Horsfall, as a warning to other owners not to install machinery. Horsfall hated the Luddites and was quoted as saying he would ride up to his saddle in Luddite blood. One night Mellor and his accomplices laid in wait in a wood alongside the road, armed with long barrel muskets. As Horsfall rode by, they shot and fatally wounded him. Unfortunately for Mellor, Horsfall’s neighbor William Parr was on the road just yards behind and saw the men. He helped Horsfall to the safety of a nearby inn, but Horsfall was too badly injured to be saved. Parr was later able to identify Mellor as one of those who attacked Horsfall.

General Maitland began the hunt for Mellor using small groups of troops to check every house and inn. They questioned the Methodist preachers, but the ministers gave nothing away about the actions of the Luddites, even though some were in their congregations. Maitland offered bribes and rewards, and Mellor was eventually betrayed, leading to the arrest of Mellor and the three men who had helped in the killing of Horsfall and 14 others accused of the attack on Rawfolds Mill.

Maitland made sure the trial in York was rigged against them. He arranged for the trial judge to be one who was known for harsh sentences given to working people for offenses like stealing and armed attack. The jury was similarly biased with over half of them drawn from the gentry and business owners.

To make matters worse, the lawyer the men had chosen to represent them was incompetent and failed to cross-examine the prosecution witnesses. The men were found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. On a cold day in January 1813, the men were hanged in groups. The gallows were built high off the ground so that the public could see the men’s last breaths.

As they were lead out to the gallows, the men sang Samuel Wesley’s hymn:

Behold the Savior of mankind nailed to the shameful tree,

How vast the love of him inclined, to bleed and die for thee

But soon he’ll break death’s envious chains, and in full glory shine

O Lamb of God was ever pain, was ever love like thine?

Jabez Bunting, the leader of the Wesleyan Methodists, refused to pray at their funeral, but he asked one of the local preachers to take the service.

What made devout Christians turn to violence so uncharacteristic of their faith? General Maitland himself was plagued by this question and set out to conduct a survey of the living conditions of the poor. He found that wars with America and France were causing shortages which doubled the price of some foodstuffs. For the poor, where food was around 40 percent of their living costs, these shortages hit much harder than on the landed rich. Mechanization was rapidly destroying skilled jobs and those working in the new factories were paid starvation wages. Often whole families, including children as young as 10, had to find work in order to survive. However, the brutality of the Luddites’ executions discouraged further wrecking of machines. It also provoked liberally minded politicians to seek to legislate to improve the conditions of the workers.

Within two years, the wars with America and France came to an end, trade in cotton and wool goods boomed, and wages rose. This created more jobs in the factories, and living standards improved. However, the much lower wages in the factories created a disparity in wealth between the factory owners and the workers which persists today.

Were the Luddites right?

The answer is complex. They were right in that high-paid, skilled jobs that had created the wealth in the village communities had vanished. They were also right in seeing the poverty that would follow. The Luddites were part of tight-knit communities linked together by their Methodism, and these communities declined as the people had to leave to seek work in the factories of the nearby cities.

But the Luddites were wrong in allowing their anger to turn to violence and were wrong in that they could not foresee the new skilled jobs that the Industrial Revolution would create: engineers to build the machines and mechanics to keep them running. Also, cheaper cloth created new markets and allowed more people to have access to quality clothing. The first department stores sold this range of new, cheaper clothing. Stores like Harrods and Sears, titans of the 20th century, were founded in this era.

So, what can we learn from the Luddites?

In addition to poor working conditions, the factor which caused so much anger among the Luddites was the rapid adoption of the new technology over a matter of ten years, which constantly eliminated low-wage jobs. Now with robotics and artificial intelligence, our generation faces similar rapid change.

Daron Acemoglu of MIT and Pascual Restrepo of Boston University estimate in a recent paper that robots have so far only taken 360,000 to 670,000 jobs in America, but that is expected to rise in the coming decades. In the UK, accountants PwC estimate in a recent research report that autonomous self-driven trucks and robotics in distribution centers will take around 56 percent of jobs in the transportation and storage sectors (around 1 million jobs). They believe this could happen in the next two decades. Daimler already has a test truck program in the USA and Germany and many other companies, including GM, Ford, and Uber, are already investing in this technology.

Change is coming at us very quickly, encouraged by governments who see additional economic growth through this technology, despite the social impact. If governments on both sides of the Atlantic are to prevent a modern Luddite reaction to rapid change, they need to plan now. Some of the impact of the loss of jobs will be softened by the retiring of the “baby boomers,” but the labor market for low- and semi-skilled jobs is expected to reduce as this technology continues to develop.

The church has a spiritual and social role that it can play in helping its members adjust to the changes as well.

The jobs that will be created by robotics will be highly skilled, demanding post–high school education. Many children from underprivileged backgrounds could succeed if they had the emotional and financial support that the middle class takes for granted. Churches and other community groups could run mentoring programs funded by local businesses. Churches and faith-based groups could lobby for more paid trade apprenticeships for jobs like construction and carpentry for young people who are more talented in manual skills than study.

Church leaders could also encourage state and national legislators to spend at least a week a year working in minimum wage jobs just to experience what life is like away from the “bubble.” The experience of working alongside those living on low wages would let them hear the daily struggle of balancing paying bills and affording basic necessities.

In areas where production jobs have already moved away and unemployment is at high levels, opiate and alcohol abuse has increased in the past decade. Churches can contribute practically as well as spiritually to bring hope back to a community by setting up social enterprises to bring community services that are needed and, at the same time, to ensure the jobs in these enterprises go to local people. Some churches, both in the UK and the US, are already doing this.

The early church encouraged the wealthy to act as patrons and employers of the poor. Today this role has moved largely to government. As such, churches should support the introduction of a social or basic wage paid to anyone who is out of work who does part-time work for local nonprofits and church social outreach ministries. To avoid the concern over the state funding religious causes, churches may have to create separate nonprofits that, though faith based are not faith biased. The Resurgo charity operated by St. Paul’s church in Hammersmith, London, is a good example.

In Scripture, work is always portrayed as being of value both to the community and the individual. Pastors can help re-enforce this in preaching. Pastors also need to spend time on the frontlines with the people in their churches, visiting where they work, seeing the challenges they face, and supporting them in the ministry of their daily lives, representing Christ in their office or factory.

Those pastors who did work in a secular role before seminary need to keep track of changes in the business world they once inhabited and be willing to offer theological critique of business practices where they conflict with Christian care for the human spirit.

Christians have a valuable social role to play in providing a moral framework for assessing technological advancement. But we can learn from the Luddites that there is a danger of violent response if the church and civic leaders do not adapt and respond to the pressures of technology on people’s livelihoods.

David Parish worked for 35 years in the transport industry for a major global company. He is now an Associate at the London Institute of Contemporary Christianity and writes and speaks on business issues.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month