By 1535, several englishmen had been or were engaged in the hunt for William Tyndale, under orders either from King Henry VIII, Sir Thomas More, or Bishop John Stokesley of London. These agents were hunting all over Europe, but only one of them actually succeeded in ferreting out the elusive Tyndale and bringing about his demise: a devious ne’er-do-well named Henry (or Harry) Phillips.

Henry Phillips arrived in Antwerp during the early summer of 1535. He came from a wealthy and therefore notable English family, and his father, Richard, had been three times a member of parliament and twice high sheriff. In addition, Richard Phillips held the lucrative post of Comptroller of the Customs in Poole Harbor.

Henry Phillips was the third and last son in the family, and in 1533 he registered at Oxford for a degree in civil law. And being a man of some ability, he was apparently well-set to gain a good position and follow a respectable life.

However, Phillips had another side to his character that now came to deter him. Entrusted with a large sum of money by his father to pay to someone in London, Henry reached the big city and gambled away his trust.

What his movements were immediately after that we cannot be sure, but three years later, in the winter of 1536–37, he wrote from the Continent a series of long, penitent letters home, expressing his terrible poverty and the fact that his dire straits would soon end his life in abject misery unless his parents held out a hand of forgiveness and assistance. He was by then being branded as a traitor and rebel, and had found himself pursued by government agents and without a friend in the world.

After squandering his father’s money in London, Phillips had evidently come into contact with someone who was still anxious to apprehend Tyndale. Phillips was virtually stranded in Antwerp, afraid to return home and unable to leave the city. A young educated man from the university, with influential connections and a known disdain for the reformers, and now in a terrible financial mess, he was the ideal person to send on a new mission to kidnap Tyndale.

We may never know the identity of the powerful dignitary who so successfully used Phillips as his front man in the arrest of Tyndale, but the prime suspicion rests upon John Stokesley. His hatred of the reformers was venomous, and he boasted of the number of heretics he had killed. Beside Stokesley, even Thomas More appeared gentle.

Whoever his master was, Phillips received his orders, a servant and a liberal supply of money, then set off for Louvain. This city was in the province of Brabant, and the town, strongly against reform, was situated about 30 miles northeast of a small village of later historical importance called Waterloo. Phillips registered as a student at the university and, to explain his apparent wealth, spoke freely of holding two good benefices in the diocese of Exeter. From Louvain he could plan his strategy and ride along the direct road to Antwerp, less than 30 miles away.

Winning Their Confidence

Phillips threw himself into the company of the English merchants, and by his silver tongue and golden hand won the confidence of all except Thomas Poyntz, the man who gave Tyndale safe lodging in Antwerp. It was not long before Tyndale, who was frequently invited to dine with the merchants, found himself in the same company, and Henry Phillips had come face to face with his prey.

Unsuspecting, the reformer felt attracted to the easy manner and eloquent speech of the young student lawyer, and before long he invited him to the Poyntzes’ home. There he dined, admired Tyndale’s small library, warmly commended his labors, and talked easily of the affairs in England and the need for reform. He even stayed overnight.

Thomas Poyntz had misgivings about the relative stranger, but when Tyndale assured him of the man’s Lutheran sympathies, he put his doubts aside. This was the greatest mistake Tyndale ever made.

Phillips won the friendship of Poyntz, and after a few days the merchant took the visitor on a tour of Antwerp, readily answering all Phillips’ inquiries about the alleys, buildings and chief officers of the town. They talked about the king and his affairs, Poyntz and his affairs, Phillips and his affairs. It was all very amicable. What Poyntz only later realized was that Phillips was also gently sounding him out to see whether, for a good bribe, he would be willing to sacrifice Tyndale. For all his astute business abilities, Poyntz apparently did not pick up the veiled message until it was too late.

Within a few days Henry Phillips had gone. He had learned enough from his new friends to know that it would be useless to work through the merchants or officers of Antwerp; a warning would almost certainly reach Tyndale before he could be seized.

He was right in this. Antwerp was full of eyes, ears and mouths. As early as April of that year the Imperial attorney in Brussels had issued a warrant for the arrest of the three leaders of English reform: Tyndale, Joye and Dr. Barnes. This warrant was passed to the leaders at the Bergen in case one of the wanted men should visit the great trade fair held in that town in April. A helpful note forewarned the Antwerp merchants of all these official communications.

Thus Phillips rode straight to the court of Brussels, 24 miles distant and just a few miles west from Louvain. Ambassador Hackett had died in October 1534 and neither Henry of England nor Charles of the great Imperial Empire was in a hurry to see him replaced. Henry had finally substituted Anne and himself for Catherine and the pope; the Bishop of Rochester, John Fisher, and the recent Lord Chancellor, Thomas More, were already on their way to the scaffold; the pope was putting the finishing touches to a Bull to excommunicate this great “Defender of the Faith,” and Charles, because of all this, was not talking to King Henry.

Phillips therefore arrived at the Imperial Court at a time when he could act as his own ambassador and with valuable information against one of Henry’s subjects. With little delay, he obtained the services of the Emperor’s attorney and, with a small party of officers, set out on the road back to Antwerp.

Poyntz was sitting unusually lazily by his door when Phillips’ servant arrived, inquired whether William Tyndale was at home, and assured the merchant that his master would shortly call back to see the translator. He did not call back, and three or four days later Poyntz left Antwerp to conduct some business at Barrow, some 18 miles from the town. He expected to be away for a month or six weeks and Phillips, knowing this, decided to strike without further delay.

He arrived at the Poyntz home about May 21, 1535, and, in his courteous and charming manner, invited himself to lunch. He then returned into the town, presumably to set the officers in their appropriate place for ambush. Phillips’ scheme was working according to plan, only requiring that Tyndale, who had already been invited out to lunch that day, cancel the arrangement made with Mrs. Poyntz and invite Phillips to join him in the town. In this he was not disappointed.

But Henry Phillips could not resist one more victory over his already-condemned prize. Almost as an afterthought he asked Tyndale if he would kindly lend him two pounds, on the pretext that he had, that very morning, lost his purse. Tyndale, who according to Foxe’s Book of Martyrs was “simple and inexpert in the wily subtleties of this world,” willingly handed over the money (enough for a poor family to live on for two months) and the two men left the house.

Ambushed!

Antwerp was, like all medieval towns, laced with twisting, narrow alleys that in places refused to allow two men to pass, and were sunless by reason of the overhanging buildings. As they left Poyntz’s home, just such an opening confronted them. Tyndale courteously stepped back to allow his guest to precede him. Phillips, a tall, handsome man, stood aside and insisted that the great reformer should have precedence.

Tyndale came to the opening and saw two officers ready to seize him, he hesitated and moved back, Phillips stood over him, pointing down with his finger as a sign that this was the man; he then jostled Tyndale forward into the officers, who bound him with ropes and brought him to the attorney’s residence and finally to the grim castle of Vilvoorde, just six miles north of Brussels.

The castle of Vilvoorde had been erected in 1374 by one of the dukes of Brabant, and since it was modeled upon the infamous Bastille, built in Paris at about the same time, its moat, seven towers, three drawbridges and massive walls made it an impregnable prison. The castle was used as the state prison for the Low Countries, and Tyndale was thrown into one of the foul-smelling, damp dungeons with nothing for company but the lapping moat, the squabbling moorhens outside, and the dripping walls and scurrying rats inside.

Here, in his solitary darkness, Tyndale waited for the end. The merchants, with all their power at Antwerp, were powerless here, and few would risk their livelihood to try to save him. His work that remained undone could never be completed. Tyndale knew he had “finished the course.”

When Thomas Poyntz galloped into Antwerp in reply to the urgent message from his wife, he discovered Tyndale’s room ransacked and all his books and papers taken. Poyntz was furious. He blamed himself, he blamed the merchants, he blamed the governor of the English House, he blamed Tyndale’s simplicity—but above all he blamed the authorities. This was an outrageous breach of the traditional privilege of the house of the English merchants. And the merchants lost no time in sending a strong letter of protest to the government of the Low Countries.

Letters of indignant complaint poured into the court at Brussels. Letters also began to arrive at the court of King Henry. And behind all this action was the never-tiring hand of faithful Thomas Poyntz. But it was a forlorn hope. Emperor Charles V was making up for lost time by turning upon the Lutherans with a vengeance, and Henry VIII, having toppled the pope over the cliffs of England, was anxious to prove he was still a loyal Roman Catholic and certainly no heretic. Just to demonstrate his point, 14 Dutch Anabaptists were sent to the stake in England within a few days of Tyndale’s arrest.

Thomas Poyntz determined to do something. He wrote to his brother John, who was lord of the manor of North Ockenden in Essex, and urged him to make representation in the court. The death of Tyndale, Poyntz urged, “will be a great hindrance to the gospel and, to the enemies of it, one of the highest pleasure.” The king never had a more loyal subject than Tyndale, suggested Poyntz, nor a man of higher reputation. Poyntz’s letter breathes a zeal and loyalty to the reformer that reveals the close relationship between the two men, and their common faith in Christ.

Though Poyntz failed in his attempts to rescue Tyndale, it must stand to the merchant’s credit that he gave himself unstintingly to his attempts, regardless of the cost to himself. Eventually, he was banished from the Low Countries, lost most of his merchant interests in consequence, was separated from his wife and family for many years and, when he finally succeeded to his brother’s estate at North Ockenden, was too poor to live there. He died in 1562, and his epitaph in the church building at North Ockenden speaks of his suffering and imprisonment, “for faithful service to his prince and ardent profession of evangelical faith.”

It is little comfort to know that for his Judas-like betrayal Henry Phillips gained nothing either. He spent the next few years fleeing from King Henry’s agents. They reached him in Rome, and then in Paris, where he arrived “altogether ragged and torn,” and where he stole some clothes from an old friend who had helped him. He once returned to London, but was forced back to Louvain, from whence he wrote the begging letters home.

In the autumn of 1538 he arrived in Italy, as a Swiss mercenary with German boots having walked from Flanders. By 1542 he passes from history, as a prisoner under threat of losing his eyes or his life. Disowned by his family, by his country, by almost every prince on the continent and even by those with whom he collaborated in his terrible crime, he died, Foxe conjectures, “consumed at last with lice.”

The Trial and Imprisonment

But back in 1535, Tyndale, shivering in the dungeons of the Castle of Vilvoorde, was too great a man to entertain any petty hopes for revenge over Henry Phillips. He had never expected his death to be other than violent; he had been too long exposed to the dangerous life of the hunted exile to waste time mourning his present state.

He knew his trial would be little more than a formality; but during that event he might have opportunity for speaking of his Savior, and thus he must prepare his defense well. In addition, he continued with the work so close to his heart, his writing and translation.

As Tyndale toiled and the autumn of 1535 faded, his chest and head labored with heavy catarrh; he shivered through the day, and shivered all night as well. As he penned his little treatise, Faith Alone Justifies Before God, winter drew on and the light began to fail; a few hours a day was all he could use for writing. The remainder of the time he sat in darkness. But he must finish his work, for this was to be his summary of the evangelical gospel; since he was going to die anyway, there must be no doubt as to why he died.

The winter was harsh, and though he was too bold for Christ to plead for release, and too wise to consider it of any value if he had, he determined to ask the prison governor, who also happened to be the Marquis of Bergen, for a few essentials to help him with his study, and to maintain a little longer the flickering life that shivered in his body. The letter was written in Latin, and it is the only letter in Tyndale’s own hand that has survived (see a copy of it in A Letter from Prison).

The letter is typical of Tyndale; there is no cringing flattery, no frantic plea for mercy, no long and tedious defense or protests of loyalty, faithful service, humble obedience and so on, all of which is so familiar in letters from 16th-century condemned cells. Tyndale asks for his needs, determines to go on with his study, longs only for the salvation of his captors, and is ready for whatever God’s sovereign purpose may be. Whether his request was granted cannot yet be told.

Finally, the long-awaited trial began. Tyndale had been in the castle for 18 months, and now everything was set. A long list of charges was drawn up:

“First, he had maintained that faith alone justifies.

“Second, he maintained that to believe in the forgiveness of sins, and to embrace the mercy offered in the gospel, was enough for salvation.

“Third, he averred that human traditions cannot bind the conscience, except where their neglect might occasion scandal.

“Fourth, he denied the freedom of the will.

“Fifth, he denied that there is any purgatory.

“Sixth, he affirmed that neither the Virgin nor the Saints pray for us in their own person.

“Seventh, he asserted that neither the Virgin nor the Saints should be invoked by us….” And so the list continued.

Early in August of 1536, the reformer was condemned as a heretic. A few days later the pageant of casting him out of the Church took place. In the town square a crowd gathered. The great doctors and dignitaries assembled in due pomp and array, and took their seats on the high platform. Tyndale was led out, wearing his priest’s robes. He was made to kneel and his hands were scraped with a knife or a piece of glass as a symbol of having lost the benefits of the anointing oil with which he was consecrated to the priesthood.

The bread and wine of the mass were placed in his hands, and at once withdrawn. This done, he was ceremoniously stripped of his priest’s vestments, reclothed as a layman, and handed over to the attorney for secular punishment. The Church would condemn, but always left it to the secular officers to stain their hands with the murder. But for Tyndale the end was not yet. He was taken back to Vilvoorde Castle and for some unexplained reason remained a prisoner for two more months.

The Execution

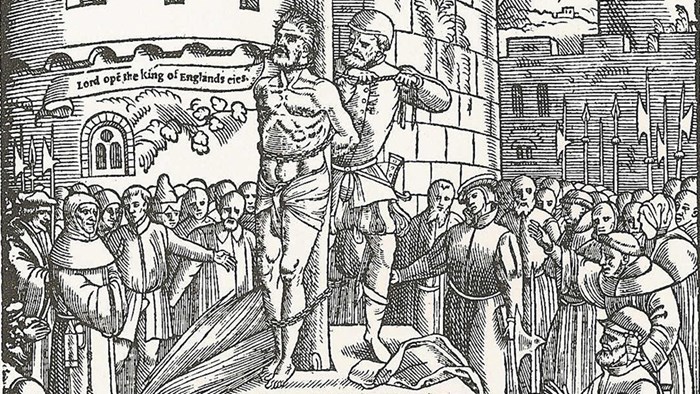

Then, early in the month of October 1536, William Tyndale was led out of the castle toward the southern gate of the town. The sun had barely risen above the horizon when he arrived at the open space, and looked out over the crowd of onlookers eagerly jostling for a good view. A circle of stakes enclosed the place of execution, and in the center was a large pillar of wood in the form of a cross and as tall as a man.

A strong chain hung from the top, and a noose of hemp was threaded through a hole in the upright. The attorney and the great doctors arrived first, and seated themselves in state nearby. The prisoner was brought in and a final appeal was made that he should recant.

Tyndale stood immovable, his keen eyes gazing toward the common people. A silence fell over the crowd as they watched the prisoner’s lean form and thin, tired face; his lips moved with a final impassioned prayer that echoed around the place of execution: “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.”

His feet were bound to the stake, the iron chain fastened around his neck, and the hemp noose was placed at his throat. Only the Anabaptists and lapsed heretics were burnt alive. Tyndale was spared that ordeal.

Piles of brushwood and logs were heaped around him. The executioner came up behind the stake and with all his force snapped down upon the noose. Within seconds Tyndale was strangled.

The attorney stepped forward, placed a lighted torch to the tinder, and the great men and commoners sat back to watch the fire burn. Not until the charred form hung limply on the chain did an officer break out the staple of the chain with his halbert, allowing the body to fall into the glowing heat of the fire; more brushwood was piled on top and, while the commoners marveled “at the patient sufferance of Master Tyndale at the time of his execution,” according to Foxe, the attorney and the doctors of Louvain moved off to begin their day’s work, never imagining that within months at least part of the plea in Tyndale’s dying prayer would be answered affirmatively.

Brian H. Edwards is the author of God's Outlaw, a 1976 book about William Tyndale, published by Evangelical Press and now in its third printing. This article is adapted from a chapter in that book, used by gracious permission of Brian and Evangelical Press. Brian is minister of a congregation in Surrey, England, and has authored four other books

Copyright © 1987 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine.

Click here for reprint information on Christian History.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month