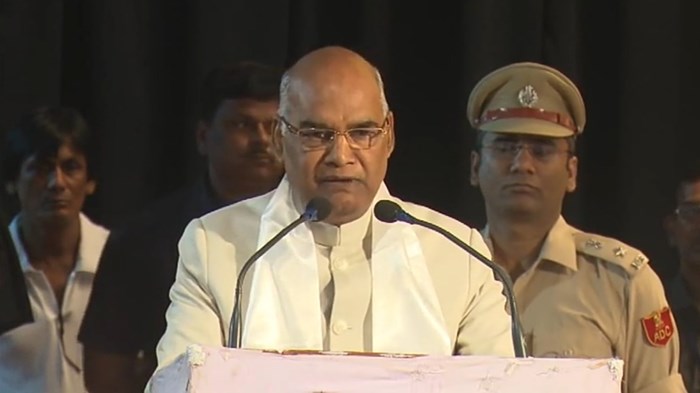

Ram Nath Kovind, India’s new president who took office today, represents an unusual case of a little-known politician from the country’s lowest caste, the Dalits, rising to power.

However, as others champion his victory, India’s Christian minority—the majority of whom are Dalits themselves—know that a Hindu nationalist politician from the Dalit caste is still a Hindu nationalist politician.

Like the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) that nominated him, Kovind represents a continued threat to non-Hindus in India, including its estimated 25 million to 60 million Christians. (As CT has noted, that’s a tiny minority amid 1 billion Hindus, but still sizable enough to rank among the 25 countries with the most Christians, surpassing “Christian countries” such as Uganda and Greece.)

If Indian officials were to move forward with anti-conversion legislation or other policies directed at Christians, “he would be a good rubber stamp for the government,” said Sandeep Kumar, a church planter and principal of Mission India Bible College, in an interview with CT. “There is no room for Christians in his understanding.”

Since 2014, India has been led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, a BJP leader notorious among Christians for permitting religious freedom violations to spread unchecked. Meanwhile, the position of president is mostly ceremonial and selected by lawmakers.

Kovind’s election this month indicates that the BJP is gaining support among Dalits (once called “untouchables”) with its polarizing vision of India as a nation whose religion, language, and culture is solely Hindu, an ideology known as Hindutva that originated among the higher castes.

When he was a party leader back in 2010, Kovind had remarked that “Islam and Christianity are alien to India” and said that they do not deserve the benefits and quotas assured to others from lowest castes, officially designated as “Scheduled Castes.”

India’s constitution has extended scheduled caste benefits to Buddhists and Sikhs, but not to any other religious minorities, officially leaving Dalit Muslims and Christians out. Most estimates suggest that at least half of India’s Christians are Dalits.

Z. Devasagaya Raj, a priest who oversees Catholic outreach to Dalits, said “the idea of appointing a Dalit person for the coveted post is largely positive but not if ‘the person holds a [pro-Hindu] right-wing ideology,’” according to a UCA News report. Though Modi endorsed Kovind as a representative for the poor and oppressed, Christians have reason to believe that won’t include them.

Samuel Jaykumar, who defends Dalit Christians as a leader with the National Council of Churches in India, told the Catholic news source that he was concerned that Kovind’s presidency would make things worse for Dalit Christians and Muslims.

Kovind’s election on July 17 followed weeks of protests from Christians and Muslims angered by attacks on religious minorities for eating beef, which angered Hindutva extremists due to Hindus’ veneration of cows. (The sale of cattle for slaughter was declared illegal in most of India this spring, until the Supreme Court suspended the ban.)

Kovind’s opponent from the United Progressive Alliance, Meira Kumar, also came from the Dalit class and had a “good track record” in foreign affairs, according to Sandeep Kumar. Regardless of the candidate, it’s uncommon for presidential politics to come up in Indian churches.

“We don’t preach on if someone has been elected and how that could benefit us,” the pastor said. “But we do pray for our country.”

K. R. Narayanan, India’s first Dalit president since the country’s independence, was a better advocate for tolerance for religious minorities when he held office from 1997 – 2002. Having grown up in the disproportionately Christian state of Kerala in southern India and studied at a church-run school, Narayanan condemned the Hindu nationalists thought to be responsible for violence against Muslims and resisted efforts to shift the secular education system.

Catholic and Protestant leaders have joined to pray for their new president.

The next general election in India will take place in 2019. There aren’t promising signs for an alternative that would be friendlier to Christians than the current administration, led by Modi, so most expect that the Hindutva ethos will continue to rule.

Though India is the biggest democracy in the world, its Hindu norms have increasingly restricted Christian freedoms. Open Doors rates the persecution level in the country as “very high.”

Christians will join in demonstrations next month designed to draw attention to the plight of Dalits. According to Asia News:

This August 10th will be a “Black Day” to highlight the discrimination suffered by Dalit Christians in India for 67 years. It is the initiative launched by the Indian Bishops' Conference (CBCI) Office of Dalits and the Disadvantaged Classes. In recent days, the bishops expressed their solidarity with the new president, Ram Nath Kovind, of Dalit origins. They also want to remind people that the country implements a constitutional-based discrimination against those Dalits that embrace Christianity.

Due to a regulatory crackdown on foreign NGOs, Compassion International was forced to end its child sponsorship operations in India in March, pulling $45 million in funding from its Indian church partners.

CT offered an in-depth cover story last year on Indian Christianity, the world’s most vibrant Christward movement.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month