Despite pervasive secularization and widespread opposition to religion gaining a more prominent place in society, large majorities in six Western European countries still support the tradition of paying church taxes.

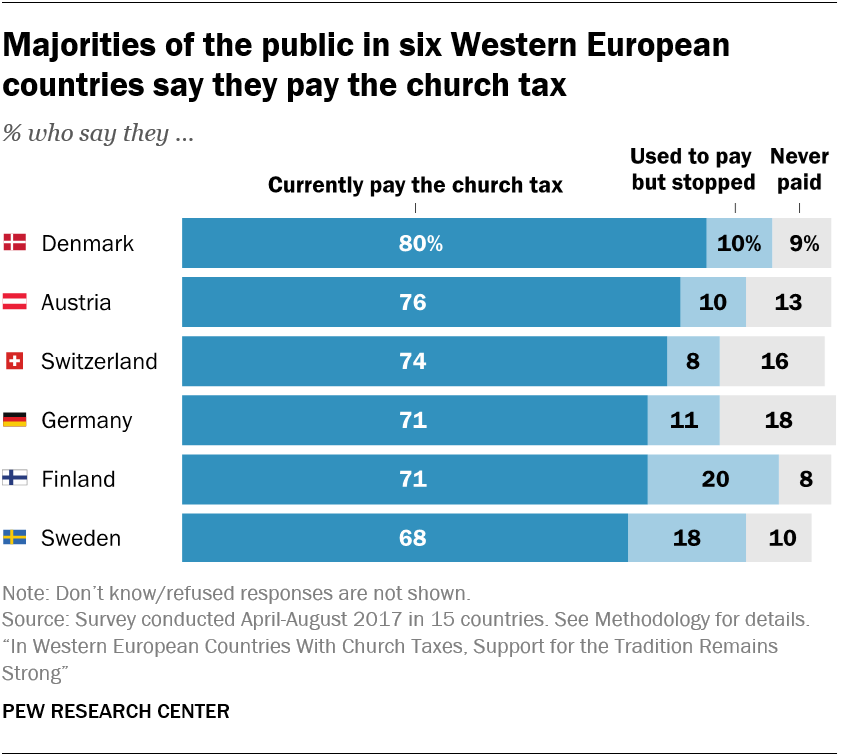

The practice may seem foreign to Americans, and particularly surprising in post-Christian Europe, but a new report from the Pew Research Center shows that most Europeans don’t oppose the tax. In each of the six countries surveyed—Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland—at least two-thirds of adult citizens, ranging from 68 percent in Sweden to 80 percent in Denmark, continue to pay the church tax.

This seems a remarkable reality as a third of Europeans, including 51 percent of Swedes, oppose a more important role for religion in their countries, according to another recent Pew study.

Typically entered into church rolls upon baptism, it can’t be denied that some Europeans are leaving the church tax system by deregistering from churches. Parties opposed to the tax have also led public campaigns and pushed legislation to inspire people to withdraw. Earlier this year, a German bishop proposed abolishing the tax to further separate church and state.

“But there doesn’t appear to be a mass exodus,” state Pew researchers. “The survey finds that between 8 percent of adults (in Switzerland) and 20 percent (in Finland) say they have left their church tax system.”

The tax employed in numerous European countries is used to fund religious organizations, covering costs such as clergy salaries, building upkeep, and “charitable services” like schools and hospitals. Despite the name, not all countries consider it a tax in the formal sense; nor is it only Christian churches that receive revenues. For example, Jewish, Muslim, and humanist groups also participate.

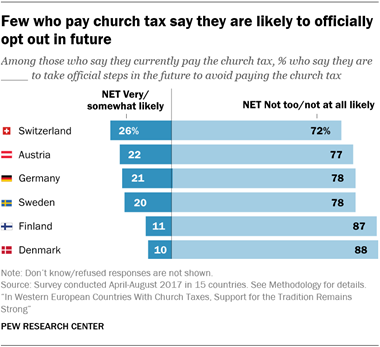

Among those who currently pay the tax—which typically amounts to between 1 percent and 2 percent of an individual’s taxable income—some are interested in getting out. Among respondents, 1 in 10 of Danish payers and 1 in 4 (26%) of Swiss payers say they are “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to take official steps to avoid paying the church tax in the future.

But the overall trend is to keep paying. Nearly 9 in 10 Danes (88%) and Finns (87%) who pay say they are “not too likely” or “not at all likely” to take action to opt out of the system. Most Swedish (78%), German (78%), Austrian (77%), and Swiss (72%) payers say the same.

Across the board, the majority of payers self-identify as Christians and most non-payers say they are religiously unaffiliated. And yet, in countries like Denmark and Sweden, strong minorities continue to pay even though they say they are religiously unaffiliated. More than a fifth (22%) of Danish adults who pay the church tax and a third (32%) of Swedish payers say they are not religious.

Areligious, antireligious, nominals, and “nones” are on the rise in Europe and church attendance is sparse. So why do people keep giving a cut of their income to religious institutions?

According to the study, the reasons vary, but a primary component is the widely held view that religious institutions support the common good.

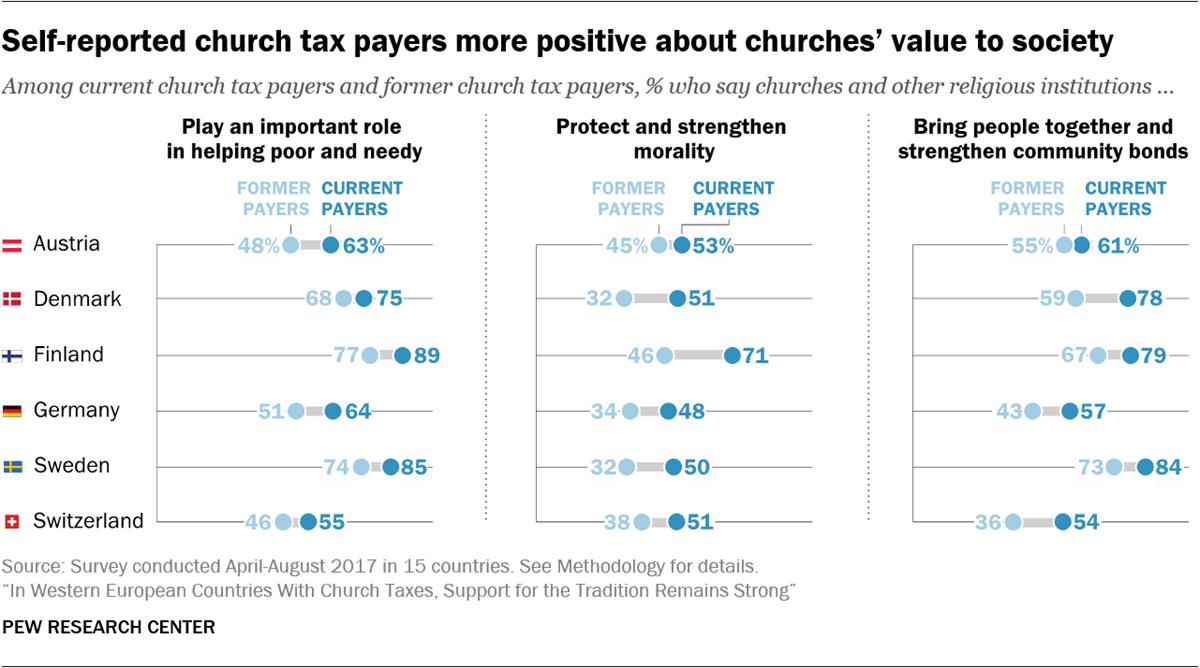

“People who say they pay the tax tend to express more positive feelings about the impact of churches on society,” say the researchers. “For example, many self-reported payers say that churches and other religious institutions strengthen morality, bring people together, and help the poor.”

More than half of payers in all six countries say churches play an important role “in helping poor and needy.” Majorities also say religious institutions “bring people together and strengthen community bonds,” including 84 percent of Swedish payers.

Current payers are also “marginally” more likely than former payers to “at least sometimes” attend services at a church or other place of worship, and to place greater significance on religious beliefs. Even so, most who currently pay the tax do not regularly attend church.

Among Danes and Swedes who pay, less than 3 in 10 (28% and 29%, respectively) say religion is “somewhat” or “very important” in their lives. In Finland, where 71 percent of adults pay the tax, a full 90 percent of those payers say they “seldom” or “never” attend church. Large majorities of payers in the other five countries say the same.

In Germany, the practice of collecting the Kirchensteuer dates back to the mid-19th century when economic and political upheaval eroded church sovereignty and pushed churches toward independence from the state, their loss of land and power actually made them more reliant on government funding. Church taxes were inaugurated in Denmark and Sweden at the turn of the 20th century, and Austria’s tax was initiated by the Nazis in 1939.

While autonomy has shifted, the partnership between church and state remains. Governments collect the tax and, after taking a fee, pass revenue on to faith-based organizations.

For many churches benefitting from the tax, it’s not just a drop in the bucket. In 2017, the Danish People’s Church collected about $1 billion from the fee, which was roughly three-quarters of its revenue for the year. The Catholic Church in Austria had a similar story that year, taking in 460 million euros, also about three-quarters of the church’s revenue.

In Germany in 2017, the nearly 12 billion euros levied comprised almost half of the revenue of the country’s Catholic and Protestant churches.

Importantly, in at least two of the countries analyzed—Germany and Austria—government records tell somewhat of a different story than citizens themselves. In both countries, more than 7 in 10 say they pay the church tax, though government estimates put the number much lower (about a quarter in Germany and half in Austria).

“Despite these discrepancies, analysis of our survey data confirms that respondents who say they pay church taxes are attitudinally different from those who do not,” stated the study authors. “At the very least, self-reported church tax payers think they are paying the tax or accept a general social obligation to pay such taxes, even if their personal circumstances might exempt them.”

Portugal and Spain, predominantly Catholic countries, are unique for their voluntary church tax systems. In Spain, 27 percent of adults say they pay the church tax. In Portugal, 14 percent choose to pay.

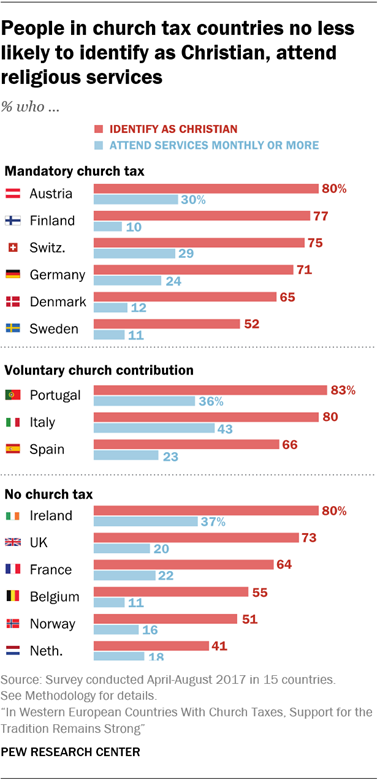

“Some social scientists have theorized that church taxes could be among the factors driving people away from religious organizations,” noted researchers. “However, a comparison of responses across 15 Western European countries surveyed by [Pew] shows no obvious connection between secularization and the existence of a church tax.”

“If anything,” they wrote, “people in countries with a mandatory church tax are more likely to self-identify as Christian than are people in Western European countries that do not have any church tax system.”

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month