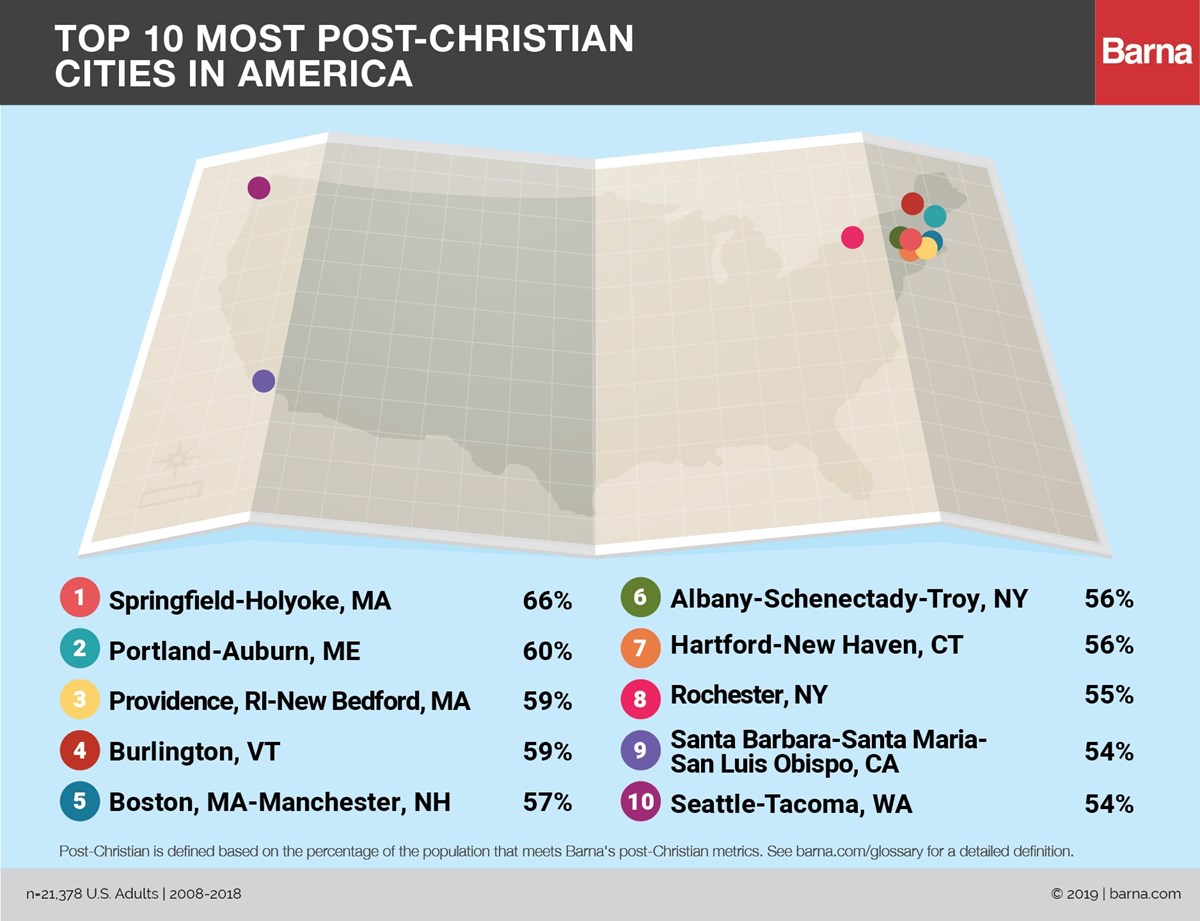

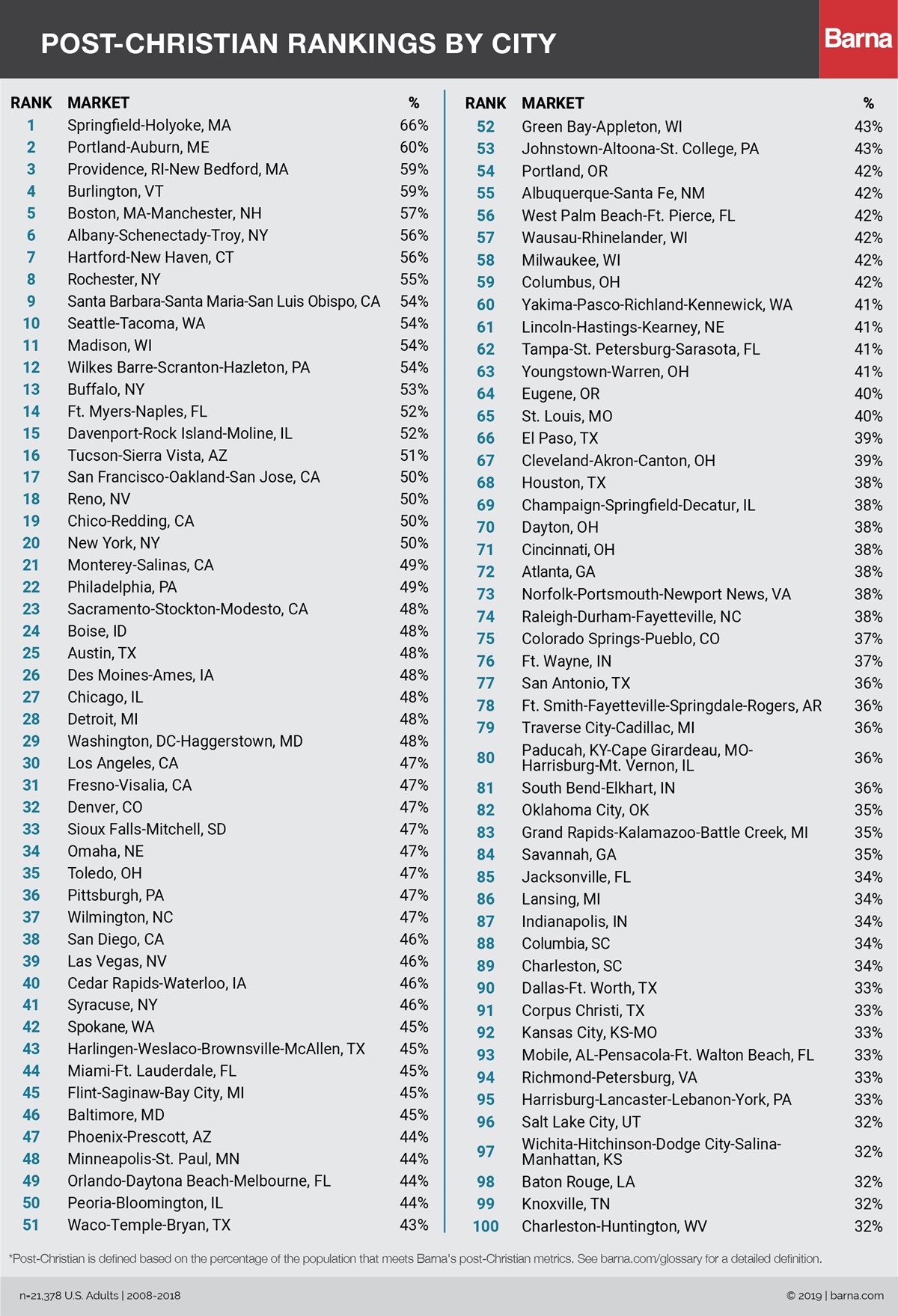

Eight locales in the Northeast and New England, a region historically known for its “righteous roots” and religious freedom, along with two West Coast spots, top the Barna Group’s annual list of most “post-Christian” cities.

Barna researchers use the designation to classify places where the fewest people follow Christian beliefs and practices, as measured by a list of more than a dozen factors.

The Springfield-Holyoke area in western Massachusetts, came in at the top of the post-Christian rankings in 2019, with a majority of residents saying they had never made a commitment to Jesus (60%), hadn’t gone to church recently (65%), and hadn’t read a Bible that week (87%). A significant minority—four in ten residents—said they did not consider faith as an important part of their lives.

Then came fellow New England metros rounding out the top 5: Portland-Auburn, Maine (moving from first place on 2017’s list to second place in 2019); Providence, Rhode Island-New Bedford, Massachusetts; Burlington, Vermont; Boston, Massachusetts-Manchester, New Hampshire.

“It doesn’t surprise us,” said Michael Kriesel, lead pastor at Vibrant Church in South Burlington, which moved up from fifth to fourth on the list over the past two years. “It’s hard to get people to go to church in New England.”

For years, Michael Kriesel, and his wife and assistant pastor, Diana Kriesel, have relied on the Barna findings to help focus their church’s mission and ministry in the Burlington area. According to the 2019 research, 59 percent of people in their city meet the designation for “post-Christian.”

“What we found was that we were living all of this [resistance to religion], and then the research came out, and put words to it,” said Diana Kriesel.

For church leaders in post-Christian cities, the stats are not signs of inevitable decline, but further motivation to pray, serve, and evangelize. “It becomes a mission field…the prayer of the Northeast: Lord, wake up New England,” said Michael Kriesel.

Connecticut pastor Eliezer Perez turned to the history of his own city, Hartford, which ranked seventh on this year’s post-Christian list from Barna and sixth on a previous release. He noted that early colonial settlers fled their homeland in search of religious freedom—a journey that quickly shifted from humble pilgrimage to the pursuit of progress.

“They had so much success that they took their eyes off of God,” said Perez, director of church development at Crossroads Community Cathedral in East Hartford. “I think we started deviating almost immediately from there.”

Completing the rest of the post-Christian top 10 are Albany-Schenectady-Troy, New York (56% post-Christian); Hartford-New Haven, Connecticut (56%); Rochester, New York (55%); and finally the only two cities outside the Northeast: Santa Barbara-Santa Maria-San Luis Obispo, California (54%) and Seattle-Tacoma, Washington (54%).

In Santa Barbara, one of the biggest battles the church is up against is declining belief overall. Christian leaders worry religion has become an afterthought, an antidotal anecdote to run to when disaster—like the 2018 California wildfires—strikes.

“People just don’t feel the need for religion. So many self-made people live here [actors, actresses, celebrities] that they still think they can do it on their own,” said Don Loomer, an elder at Santa Barbara Community Church.

He has served in SoCal churches for 30 years, surrounded by celebrities, great wealth and great weather. “People hardly think about [God]…If the suns out and the surf’s up, you say goodbye!”

Yet, in his area and post-Christian cities across the country—from Reno to New York—churches recognize that people will no longer come to a service for the sake of it. In this context, it takes a sincere effort to evangelize, but it also offers the opportunity for greater transformation.

“You really have to build some in-depth relationships before you can feel the freedom to share with people,” says Loomer. “That’s part of the reason that God had to become a man—he had to come down and live among us so that we could understand what [the gospel] is all like.”

Post-Christian cities across the country have also become destinations for immigrants, as refugees from Africa, Bhutan, and Bosnia land in Burlington, Vermont, and migrants from Central America and Mexico make their way into California. These population shifts have also affected the cultural and spiritual tenor of “secularizing” cities.

More than metrics, the Barna list is motivation for evangelical churches everywhere that are filled with pastors, leaders, creatives, and servants—every day people who aren’t afraid of these facts, but instead are fueled by them and holding out hope.

“Post-Christian doesn’t mean anti-Christian,” said Perez, the Connecticut pastor. “If it’s post-Christian, then that means there is Christian.”

Rachel Kang is a Charlotte-based writer. She is the creator of the online writing community Indelible Ink Writers.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month