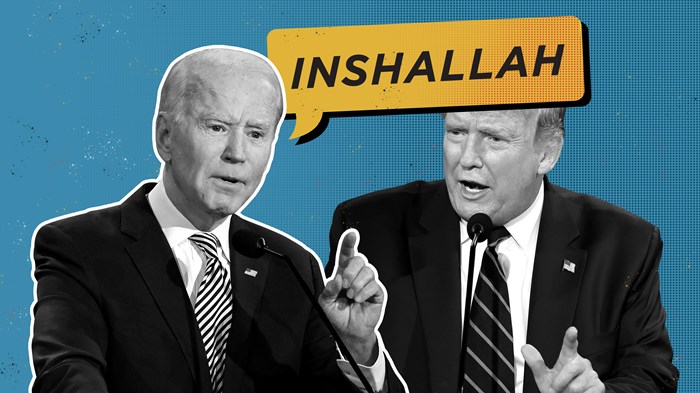

Unnoticed by many during the contentious first presidential debate, Joe Biden introduced a new Arabic word into the American lexicon.

Inshallah.

Technically, it is three words, in both Arabic and English: “in sha’ Allah,” or “if God wills.”

However, “If you take it literally, you won’t get the intent,” said Ramez Atallah, general director of the Bible Society of Egypt.

“It can also mean, ‘It will never happen,’ and this is probably what Biden meant.”

Asked by the debate moderator about his tax returns, President Donald Trump answered, “You’ll get to see it.”

To which the former vice president interjected, “When? Inshallah?”

Trump continued, and the moment was lost to almost all but Arabic-speaking viewers. Muslim Twitter users lit up in astonishment, wondering if they heard correctly.

“Enchilada” was about as close as other ears heard.

But while one Muslim writer has humorously called inshallah the Arabic equivalent of “fuggedaboudit,” what should Christians make of the phrase?

“Everything is uncertain,” Atallah said. “We live in an unpredictable world, and no one is ever sure that what they plan will be accomplished.”

He highlighted the biblical equivalent in James 4:15: “You do not even know what will happen tomorrow … Instead, you ought to say, ‘If it is the Lord’s will, we will live and do this or that.’”

Born in Egypt but educated in Canada and the United States, Atallah returned for good in 1980 and was soon given a crash course in inshallah. Calling a plumber to fix his leaky pipe, he paid about $28 in US dollars in advance and then waited endlessly for the man to come.

“Tomorrow, inshallah,” he was told.

Eventually the plumber came. He was not a thief. But whereas in the West, routine services can expect completion with relative dependability, Egypt has the Mugamma, a Soviet-style government administrative building in downtown Cairo.

Films have been made about the endless runaround needed simply to get stamps on paperwork.

“You have to live by faith here,” Atallah said, “more than you do in a Western culture.”

And Christians do—but not necessarily the way James, the brother of Jesus, imagined.

“I use the phrase all the time,” said Martin Accad, chief academic officer of the Arab Baptist Theological Seminary (ABTS) in Lebanon.

“But I’m not sure if anyone ever uses it meaningfully.”

The Arabic language has several phrases that deflect from giving a straight answer. But whether expressing a general hope or escaping a promise, in the unconscious mind of even the most flippant user is a cultural absolute.

“It is arrogant, and almost a rebellion against God, to say something without that formula,” said Accad. “Inshallah is the biblical and Qur’anic medicine against thinking that life is under your control.”

The wording in Islam’s holy book is almost exactly similar to James 4, he noted. But its presence in the story of Abraham sacrificing his son indicates how thoroughly the biblical understanding permeated Arabia’s seventh-century culture.

“O my father, do as you are commanded,” says the unnamed character Muslims understand to be Ishmael. “You will find me, if Allah wills, of the steadfast.”

This is the sense in which pious Muslims intend the phrase, said Accad, who oversees ABTS’s programs of interfaith engagement. But over the centuries, a misapplied Muslim understanding of fatalism has in turn permeated many Middle Eastern Christians.

“Saying ‘if God wills’ can lead to the giving up of responsibility, rather than following through while trusting the results to God,” he said.

“So in practice, if someone tells me, ‘Inshallah,’ I will generally ask for more assurance.”

To distinguish themselves from this cultural practice, many Arab evangelicals simply change the phrase to in sha’ al-rabb (“if the Lord wills”) or bi izn al-rabb (“with the Lord’s permission”).

Rabb is appropriate, Accad said. The original Greek word is kyrios, and the most popular Arabic translation renders it in James 4:15 as Lord.

Meanwhile, Allah is the Arabic translation for both Elohim and Theos, the Hebrew and Greek words for God in the Bible.

The Catholic Arabic Bible translates the James text as Allah, however. So does the ecumenical Mushtaraka version—similar to the Good News Bible—which Accad said feels more natural to the reader and uses the expression common to both Christian and Muslim Arabs.

But when Imed Dabbour first became a Christian, some Arab believers advised him to avoid saying inshallah.

Raised a Muslim in Tunisia, Dabbour used the phrase instinctually.

“It is a common formula to show our faith, that everything is in God’s hands,” he said. “Muslims use it when referencing the future—whether we mean it or not.”

Uncomfortable with giving up inshallah, Dabbour has since reconciled with the phrase, and with his culture at large. Today he is CEO of the Lighthouse Arab World media production house and is a TV host with experience on several national Arab channels.

He is also outspoken about his Christian faith and produced Augustine: Son of Her Tears to re-introduce North Africa to the early church father.

Tunisians use inshallah in both its positive and negative connotations, Dabbour said. But he wonders if many will be just as uncomfortable with Biden’s use, as he was.

“Some Muslim viewers may say ‘Wow,’” he said, noting Biden was likely trying to appeal to them.

“But others might be offended by the mocking tone, as he used it with the colloquial implication that we are people who don’t keep our word.”

So even if America isn’t ready for Arabic, Middle Eastern Christians offer strong testimony on the term’s behalf.

“We are much closer to James’s intent,” Atallah said. “We should say inshallah.”

Editor’s note: CT previously explored the meaning of two other key Arabic terms—taqiyya and takfir—as well as why many Southeast Asian Christians call God Allah.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month