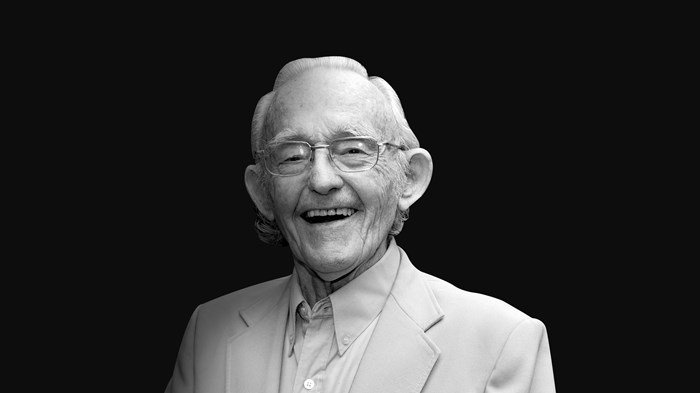

Juan Stam, a theologian who advocated for radical evangelicalism in Latin America, has died at the age of 92. A missionary to Costa Rica who once taught Communist revolutionary Fidel Castro about the Christian idea of apocalypse, Stam devoted his life to teaching the Bible, challenging both legalism and liberalism, and raising up and empowering local leaders.

Stam’s ministry—whether teaching theology at the Latin American Biblical Seminary, ministering to Marxist revolutionaries and refugees, or defending the biblical idea that God intervenes into history—was always grounded in three convictions: a personal commitment to Christ as Lord, an incarnational model for life and mission, and a love of the Bible and “radical seriousness in its interpretation.”

“His faithfulness to theological reflection, firmly anchored in solid Bible reading, and in interpretation very well placed in the historical and social coordinates, is an example worth imitating in Latin America,” wrote Mexican theologian Leopoldo Cervantes-Ortiz. “His memory will go on as a constant encouragement for the life and witness of Christianity in this part of the world.”

Jaime Adrián Prieto Valladares, a Costa Rican theologian, said that Stam “taught me to love the Word that comes from God with a passion, and to turn it into a live commitment to the poor” and “always challenged us to follow Jesus radically!”

Stam was born in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1928, part of a Dutch Christian family that embraced the end times teachings and biblical devotion of D. L. Moody’s ministry. Stam joked that he was born with the Bible in his hands, but it was the Scofield Reference Bible that laid out dispensationalist theology and open to the book of Revelation.

Then known as John, he attended Wheaton College with plans to become a history professor. He changed his mind while reading Augustine for a term paper. Stam fell in love with theology and pivoted to focusing on full-time ministry. After graduating, Stam spent two years at Wheaton’s grad school and then two more years at Fuller Seminary. He learned, he later said, “to always strive to be truly ‘evangelical,’ neither fundamentalist, on the one hand, nor liberal (à la Schleiermacher or Fosdick), on the other.”

Stam went on to earn a doctorate in Switzerland at the University of Basel, studying under theologian Karl Barth, among others. His theology differed from Barth’s, but he learned how to think theologically while never abandoning the core simplicity of the message. “He was thankful to have studied under the most important theologians of the 20th century, whether or not he agreed with their specific theological views,” remembered his daughter Rebecca.

Stam and his wife, Doris, moved to Costa Rica as missionaries in 1954. They landed in rural Santa Cruz, where they could work on their language skills, learn to live in Latin America, and gain experience in a local church before moving to teach at the seminary in San José. During their 15 months in the area, the Stams also worked with the many Nicaraguan refugees fleeing the violence of the US-backed military dictatorship led by Anastasio Somoza Debayle. Listening to the local farmers, the indigenous people, and the refugees challenged their previous view of the world.

“Though it was painful to hear criticisms of our country of birth, we soon realized how little we understood Latin American reality and how much we could learn by listening to the nationals as equals (or better, superiors),” Stam later wrote. “Our contacts with these refugees radically changed our political perspectives and converted us into lifelong activists for justice.”

In 1957, Stam took a position teaching systematic theology at the Latin American Biblical Seminary. At the time, it was the only accredited evangelical seminary in Latin America. Despite its name, the school’s leadership and culture were North American, influenced by the many US missionaries who had worked there. Stam, committed to contextualizing theological truths and embodying the Incarnation in his ministry, was interested in changing that.

“John and Doris are not part of the typical litter of missionaries in Latin America. They truly incarnated within the context. They became citizens of Costa Rica,” said Otto Kladensky, an Ecuadorian-born church leader who now serves in Costa Rica. “They bought a house instead of renting.”

The first policy Stam took on was a prohibition on student dating. After numerous debates and memos, the faculty changed the policy so that students with passing grades and up-to-date homework could date. When Stam introduced the policy, he informed students that if they did not comply with the 10 p.m. curfew or other restrictions, they would be punished for two weeks and allowed to leave their rooms only for meals, classes, and chapel.

To Stam’s surprise, the students were offended and responded with anger. One student informed him that he was “offending their dignity” by announcing the punishments in advance and that predetermining punishments was not acceptable.

“I will always be grateful for this example of what missionaries can (and should) learn from our Latin American brothers and sisters,” Stam later wrote.

Next, against the wishes of the school’s more conservative faculty, Stam began looking for ways to hand over authority to locals. His solution, ultimately adopted by the school, was to allow the seminary’s brightest students to begin teaching classes. Within a decade, the seminary had its first national rector and had begun to attract a number of Latin American faculty.

By the 1960s, Stam was accepting invitations to speak across Latin America, frequently on the topic of “Christ and Marx,” where he surveyed the ways contemporary theologians addressed social justice issues. As he traveled to Venezuela, Colombia, and Peru, he grew frustrated at how many Christians were not concerned about issues of justice and also incredibly anxious about appearing too sympathetic to Marxist complaints about injustice. In one community, he learned about a Christian couple who had been forced to feed breakfast to some guerrilla soldiers and then put in prison for their “support” for the revolution. He suggested the Christians visit them in prison—only to be told that would be a bad testimony. In another Christian community, people debated whether women should wear lipstick.

“With all due respect for evangelism and church planting,” Stam said, the urgent need in Latin America was “turning fundamentalists into evangelicals.”

At about this time, Stam began to march alongside workers and to participate in Éxodo, a social justice movement led by Methodist bishop Federico Pagura. In one seminary class, he had students write papers on the political, socioeconomic, and religious situation of their countries. For some students, just the idea that pastors should care about the political and economic conditions of their countries was a revelation.

“Juan was more than a brilliant mind; he was, above all, a sensitive human being, with a happy smile (often laughing) committed to the social causes of Latin America,” said the Colombian-born faith and development director for World Vision Latin America and the Caribbean, Harold Segura, who has lived in Costa Rica for 20 years. “Every May 1, as long as he was able to do so, he joined the workers' marches in solidarity with their causes. It was his way of confirming his commitments of faith.”

As the years went on, though, Stam found a number of younger faculty rejected the church for politics and started arguing that the theology of God’s grace was a tool of oppression, since it convinced people to be passive. They said that God cannot intervene into human history and the hope of humanity is the revolution of the proletariat. When that faction took over the seminary in 1980, Stam resigned.

Separated from any institution, Stam became a regular speaker at churches and universities across Latin America, developing especially close connections with a number of youth movements. In the process, he became a kind of freelance theologian, widely respected by Spanish-speaking evangelicals.

Stam also began ministering to the Sandinistas—Marxist rebels attempting to overthrow Nicaragua’s military dictatorship. Beyond immediate relief for refugees, Stam also began serving at safe houses for the fighters, offering weekly meditation and teaching the Bible.

The Marxist rebels asked Stam to teach them about the book of Revelation. They had heard about—but were unclear on—the revolutionary concepts of “the millennium,” the “pretribulation rapture,” and “Gog and Magog.” Stam started teaching workshops on the book and eventually wrote a four-part, 1,600-page study of John’s visions.

In 2002, he was invited to explain Revelation to Communist Party leaders in Cuba and was unexpectedly pulled in to a late-night conversation with Fidel Castro. The revolutionary leader had questions about Revelation and began interrogating Stam and the other gathered evangelicals about the book.

Stam told him the dark visions of the prophet were calls to repentance and that the word apocalypse is frequently misunderstood. It doesn’t mean catastrophe or disaster, but unveiling or manifestation of hope in Christ.

Castro excused himself at 2 a.m. for another meeting, but before he left, he asked the ministers to explain evangelicalism to him. “Explain what that means,” he said. “Who knows, I might be one without knowing it.” They explained the gospel and then prayed for him.

In his later years, Stam was not able to travel as much but continued to have an outsized influence in Latin America and inspire “radical evangelicals.”

“What distinguished Stam was the reliability and honesty with which he carried out his task as a theological educator and interpreter of the Word of God,” wrote Peruvian theologian Samuel Escobar.

Stam is survived by Doris, three children, five grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month