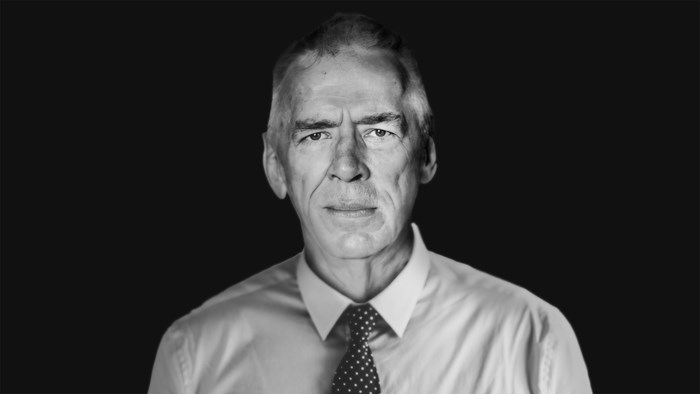

When it came down to it, Ole Anthony would admit to a lot of the bad things people said about him.

“My own grandiose bull— can get in the way,” he told a reporter in 2004. “I was a schemer and a promoter. That’s just the way my mind works.”

Anthony needed to believe he was special, and he convinced those around him they were part of a spiritual elite. He was at times a huckster. He never stopped being a hustler. He exaggerated and lied about his life to impress people. He dreamed up grand plans to feed his ego and confirm his unmistakable charisma, never letting anything be reined in by humility or other people’s good sense.

But in the process he preached a message of God’s grace to those who wouldn’t have heard it otherwise. He founded a radical community of Christians committed to recreating the first-century church. And he took on the work of exposing televangelists who perverted the name of Christ for financial gain as cheap frauds.

According to the small church he founded in Dallas, Anthony was “more like an Old Testament prophet” than anything else.

“Any conversation with him left you pondering your relationship with God,” said Gary Bucker, an elder at Community on Columbia.

John Rutledge, another elder, said Anthony’s Bible teaching “could cut through a listener’s fog of self-delusion and clarify the need for redemption. It did for me, at least.”

Anthony died on Friday, April 16, at age 82. A long-time pipe smoker, he was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2017 and it spread to his liver and his brain. He stopped teaching his daily 7:30 a.m. Bible study about two years before his death. In some of the final recordings, his pain and struggle are audible.

“There’s nothing left to do and there hasn’t been anything left to do since Pentecost,” Anthony taught in March 2019. “There's nothing left to do. That’s which is perfect has come. Do you see how important that is, that there’s nothing left to do?”

‘You were meant to be a failure’

Anthony was born in Minnesota on October 3, 1938. His family moved to Wickenburg, Arizona, a desert town billed as the “dude ranch capital of the world,” when Anthony was 10. His father left sometime after, and his mother ran a small nursing home.

By his account, Anthony was a wild youth who got into trouble with girls, drugs, and the law. A reporter for the Dallas Observer found, however, that he worked at a Safeway grocery store, belonged to the National Honor Society and his high school’s radio club, and coedited the yearbook. There was no evidence he got in any significant trouble.

At 18, he joined the Air Force and was stationed in South Korea. Anthony became a special weapons maintenance technician. He later inflated that to “surveillance operative and analyst,” telling stories about how he worked as a spy “behind the bamboo curtain” in Communist-controlled parts of Asia and witnessed nuclear tests in the South Pacific, including one memorable explosion that he said “vaporized an entire island.”

Anthony’s commanding officer, Captain William D. Ballard, said that wasn’t quite accurate, telling one reporter, “we were not that kind of field operation.” According to Ballard, Anthony installed seismic monitoring systems to detect secret nuclear weapons tests around the world.

“Ole always pushed the edge,” Ballard told another reporter. “I wouldn’t have guessed that he would become so religious. But, when he gets into something, he gets into it right up to his eyeballs.”

After he got out of the Air Force, Anthony returned to Texas and got involved in Republican politics, working as a consultant for Barry Goldwater’s presidential campaign in 1964 and a regional campaign manager for Texas Senator John Tower in 1966. He ran for state legislature himself in 1968 and lost.

Anthony launched a political PR firm in Dallas in 1971, but then had his life changed by Norman Grubb, a British missionary to the Belgian colony of Congo, who spoke about the meaning of the Cross and dying to self.

“The words that really got to me,” Anthony later said, “were: ‘You were meant to be a failure. That is the only way God can use you. Look around you with honest eyes. Don’t you see that all human effort is futile, empty and vain? All that is necessary for you is: Abandon yourself, pick up your cross and follow Him.’”

He frequently compared the conversation experience to a nuclear blast—“If you understand that God wants complete surrender from you, it’s like an atomic bomb going off in your head”—and made up a story about how he’d seen a bomb test. His friend, journalist John Bloom, who became famous in Texas for writing a satirical column about drive-in movies under the name Joe Bob Briggs, said that Anthony was trying to communicate the “mystical flash of understanding” he experienced.

“It’s impossible to explain how these things happen,” said Bloom, who had his own conversion in 1984.

A community is born

Anthony was changed enough that he abandoned his PR firm and started Trinity Foundation, named after the world’s first nuclear test site in New Mexico. He planned to organize and promote evangelistic events, but failed almost immediately. He tried to buy a TV station, but didn’t succeed. He hosted a radio show that was moderately successful in the region, but then got canceled, possibly for being difficult to work with.

“One by one all of Ole’s projects for God came to nothing,” Bloom wrote. “By the time I met him, the Trinity Foundation appeared to be comatose. In fact, it was just being born.”

In 1974, the Trinity Foundation was reduced to a Bible study. Anthony hoped it would attract the Republican officials and businessmen he had previously worked with, but it actually drew people on the margins of Texas society, with trauma and trouble and a need for the message that Jesus loved the downcast and downtrodden and did all the work that needed to be done on the cross.

“The people who showed up didn’t just bring their Bibles,” Bloom said. “They brought teenage pregnancies, divorces, bad-check charges, warrants, feuds with parents, child-custody battles, drug habits, alcoholism, car wrecks, and more or less constant illness without benefit of medical insurance. All these trauma dramas poured into the Bible study, sending Ole to the passages in which Paul exhorted Christians to embrace their afflictions and glory in their adversity.”

Anthony, going back to those New Testament exhortations, became fixed on the idea that Christians today should be more like the first-century church. He and his followers committed to sharing all that they had with each other and with anyone else in need, following Acts 2:42–47.

They bought housing on one street and called it “the Block,” meeting for daily Bible studies, shared meals, and day-to-day discipleship.

Members agreed to take in homeless people, and Anthony devised a short-lived but much publicized plan to solve the homelessness problem, with every church in the country to take in one or two people in need. Few congregations signed on for the project, though some Dallas churches would send people to the Block with a note they weren’t set up to help but knew that Anthony was.

Anthony was also influenced by a Messianic Jewish leader named Zola Levitt, and the community started celebrating Jewish feasts and fasts, interpreting Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Purim, Pentecost, the Feast of Ab, and other celebrations as texts about Jesus.

According to the church today, each feast is “like a piece of a jig-saw puzzle in time” and “when the picture is complete, we find ourselves gazing at a portrait of Jesus Christ.”

Accusations of spiritual abuse

In the radicalism and the reinvention of the Block, some people were hurt. According to former members, the community lost any sense of personal boundaries, and Anthony dominated the group with his charisma, masking his will as group consensus and controlling people’s lives. He decided who could get married. He told people where to live. He gave away their belongings and put homeless people in their homes without asking.

Perhaps the most destructive practice was a scapegoating ritual the Block called “the hot seat.” One person—commonly someone who had pushed back against Anthony, former members say—would sit in the center, and the group would assault them with accusations until they broke down.

“It was brutal,” said Powell Holloway, who sat in the hot seat in 1986. “The whole purpose was to die to self, to get in touch with the fact that you were chief of sinners.”

When people finally psychologically crumpled, they would stop resisting the worst accusations against them and embrace self-loathing and shame. Members would frequently confess to the worst sins they could imagine, including pedophilia, voyeurism, bestiality, incest, and prostitution. While some of the confessions were true, more were made up to demonstrate total submission to the group.

Anthony, as the leader, did not sit in the hot seat, former members say.

The current church says the community has grown and evolved since then and no longer practices the hot seat. The church nonetheless acknowledges that Anthony’s vision of “full-contact Christianity” could be confrontational and abrasive.

Investigating televangelists

The small group of intense Christians came to national attention in the early 1990s, when Trinity Foundation started investigating televangelists. One of the members of the community told Anthony that when he fell on hard times, he pledged his last $5,000 to Robert Tilton, host of Success N Life, a prosperity gospel program that was on the air in more than 200 television markets.

“I needed some snake oil, and he had some snake oil to sell,” Harry Guetzlaff would later say. “It made perfect sense at the time. I believed that God was active in my life, and Tilton was saying, ‘Give me a buck and God will give you back a hundred.’”

Anthony and the group were offended by this betrayal of the gospel, and tried to get someone to do something. They contacted National Religious Broadcasters, but got no response. They connected a local prosecutor, but the district attorney was not convinced that Tilton, a cartoonish character who would shadowbox demons on the air, was doing anything illegal. They contacted various media but got no response, until a producer at ABC told them they would need to produce evidence to get any attention and offered a few suggestions for how to find it.

They found what they were looking for in dumpsters behind Tilton’s office, his lawyer’s office, an Oklahoma bank branch, and a computer data management office. Trinity found Tilton was depositing the checks, computerizing the information in the prayer requests, and asking for more money by direct mail. Hundreds of thousands of papers he had promised to read, pray over, and lay hands on were ripped up and dumped in the trash.

“It was literally widows and orphans,” Anthony said. “That’s who supports the televangelists—the weakest, most vulnerable people in the world.”

On November 21, 1991, ABC aired a prime time investigation into Tilton and two other televangelists, using the evidence gathered by the Trinity Foundation. Diane Sawyer interviewed Anthony and shared footage of the trash he and the newly born “garbologists” had collected. Shortly after the program, five agencies announced criminal investigations into Tilton, and his ministry collapsed.

Trinity went on to do more than 300 other investigations into televangelists, including Benny Hinn, Kenneth Copeland, and Paula White. The ministry received support from hundreds of donors across the country, sent church members to be trained and licensed as private investigators, and became the only full-time media ministry watchdog organization.

In 1996, the foundation acquired the evangelical satire magazine The Door and occasionally used it in the war against televangelists as well, such as the time it published a Playboy-style photograph investigators had found of a naked W. V. Grant shortly after he was convicted of failing to pay back taxes.

The church and Trinity Foundation were eventually established as independent operations, though they remained closely connected. The church was named Community on Columbia.

In 2007, when a US Senate committee led by Republican Chuck Grassley started investigating prominent televangelists, with an eye toward tightening tax regulation on multibillion-dollar media ministries, Trinity gave the government 38 reports. The Senate’s final report did not result in any push to change the law.

Anthony was undeterred and spoke out against televangelists when they supported Donald Trump in 2016. He continued to work with journalists interested in exposing prosperity gospel fraud, all while maintaining his daily Bible study and participating in life at Community on Columbia. He took as its motto a Latin phrase attributed to Martin Luther: “Crux sola est nostra theologia,” meaning, “The cross alone is our theology.”

In the end, Anthony’s message to the televangelists, the needy people who showed up at the Block in Dallas, and his own grandiose schemes were one and the same. As he explained it once to Bloom, “A lot of these people are clinging to their miserable little self-images. They don’t understand that it’s about God. It’s about them, but only the part of them that contains God. They still think they’re special.”

Anthony never married. He will be buried by his nieces in St. Peter, Minnesota. A memorial will be held in Dallas on May 1.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month