At most denominational conferences these days, leaders have to recognize and reckon with the challenge of continued declines in membership. But for the US Assemblies of God (AG), which drew 18,000 registered attendees to its General Council meeting in Orlando last week, it’s a different story.

The world’s largest Pentecostal denomination, the Assemblies of God has been quietly growing in the US for decades, bucking the trend of denominational decline seen by most other Protestant traditions.

At three million members, the Assemblies of God is far outsized nationally by groups like the Southern Baptist Convention, which is more than four times as large. But in many ways, the Assemblies of God can provide a case study for what many Southern Baptists—and really, all Christians—want to see: steady and sustainable growth.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly why the Assemblies of God has continued to increase over the past 15 years. Research shows that membership of the Assemblies of God has become more politically conservative and more religiously active today than just a decade ago, but its own numbers indicate that it has achieved incredible racial diversity—44 percent of members in the United States are ethnic minorities. A confluence of these trends may be factors in its ability to keep its numbers up.

Compared to the two largest Protestant denominations in the United States—the Southern Baptist Convention and the United Methodist Church—the Assemblies of God has always been outnumbered. In 2005, there were about 16.3 million Southern Baptists in the US, by the denomination’s own tally, and nearly 8 million United Methodists. At the time, the Assemblies of God reported 2.8 million members.

However, between 2005 and 2019, both the Southern Baptists and the United Methodists reported a membership decline. In 2019, there were 14.5 million Southern Baptists, down 11 percent. The United Methodists reported a total of 6.5 million members in 2019, down 19 percent. Meanwhile, the Assemblies of God grew over 16 percent to nearly 3.3 million members.

While other denominations have been dropping year-over-year for more than a decade, there have only been three years in the past 40 when the Assemblies of God did not report annual growth in adherents. Just one of those came this century. As a result, the Assemblies of God has managed to add nearly half a million members since 2005.

As it has grown over the decades, the Assemblies of God has maintained its Pentecostal theological distinctives, like believing in divine healing, practicing spiritual gifts like speaking in tongues, and anticipating a premillennial second coming of Christ.

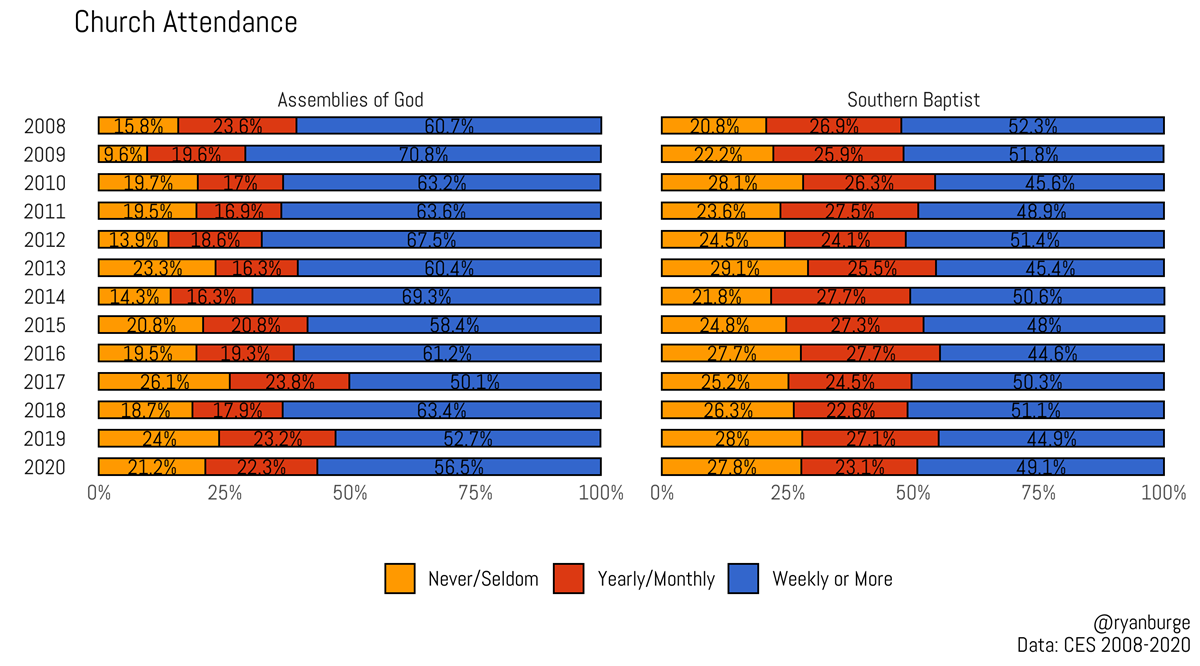

When analyzing survey data on the church attendance patterns among traditions, it’s clear that the Assemblies of God is not growing by adding lukewarm worshipers to its ranks and church roles. Instead, the data point to a denomination that is incredibly active in congregational life. On average, about a third of US Christians attend church weekly. In 2020, the Cooperative Election Study reported that 57 percent of AG members attend church at least once a week, compared to 49 percent of Southern Baptists.

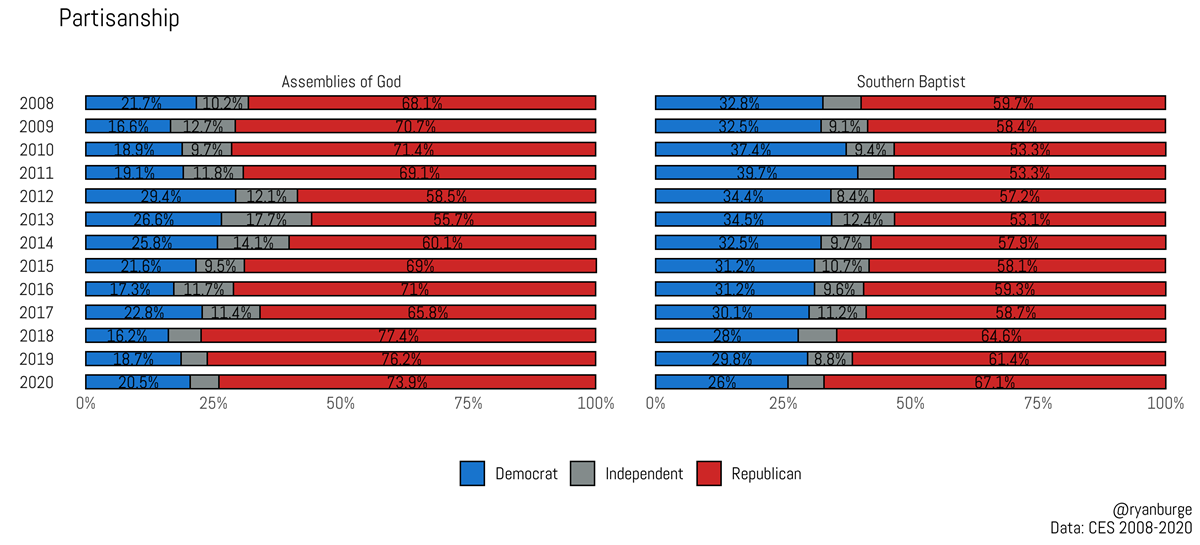

When the analytical lens turns to political partisanship, a more nuanced story emerges of how the AG has shifted compared to the Southern Baptists.

During the 2008 presidential election, about 22 percent of AG members identified as Democrats compared to 68 percent who affiliated with the Republican Party. Among Southern Baptists, the differences weren’t as stark. About a third of Southern Baptists were Democrats and 60 percent were Republicans.

Over the past 12 years, both traditions have drifted toward the right. In 2020, nearly three-quarters of all AG members said that they were Republicans, up about 5 percentage points. Among Southern Baptists, 67 percent claimed to be a Republican, an increase of 7 percentage points. But the share of AG members who are Democrats remained basically unchanged during that time, while declining nearly 7 percentage points among Southern Baptists.

Pastors, denominational leaders, and those in the pews are always interested in what leads to a denomination’s growth, particularly when the group is growing year after year while others around it experience decline. The Assemblies of God currently has around 13,000 congregations, more than a quarter of which were formed in the past decade.

It’s difficult to pinpoint just one reason for the increase in membership, but the data do paint a portrait of a membership that is very involved in the life of the church. When half of all members report weekly attendance, this goes a long way in warding off defections to other denominations. Research shows that such involvement makes it more likely that young people raised in the tradition will not leave it as they move into adulthood. More than half (53%) of AG adherents are under 35.

The fact that its churches are so politically homogeneous may work in its favor as well. Research has increasingly shown that more and more Americans are choosing their churches based on political considerations. If this is the case, then AG churches portray a clear message to potential converts about their political orientation, making it easy for newcomers to know what the church is about.

Finally, it may be helpful that the Assemblies of God, though growing, is small enough to lay low in the national media, largely avoiding the controversy and attention toward infighting in other denominations.

As the nones continue to rise and more and more nondenominational churches are planted in the United States, it will likely become more difficult for the Assemblies of God to sustain its growth.

As I describe in my forthcoming book on surveys—20 Myths about Religion and Politics in America—almost no traditional denomination has seen any growth in the past 12 years, so the Assemblies of God is a true outlier. It seems to have found a combination of factors that has succeeded even in these difficult times.

Ryan P. Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public, and he tweets at @ryanburge.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month