Egyptian Christians have long struggled to build their churches.

But now, they can have Muslim help.

Last month, Egypt’s Grand Mufti Shawki Allam issued a fatwa (religious ruling) allowing Muslim paid labor to contribute toward the construction of a church. Conservative scholars had argued this violated the Quranic injunction to not help “in sin and rancor.”

The ruling is timely, as the governmental Council of Ministers recently issued an infographic highlighting the 2020 land allocation for 10 new churches in eight Egyptian cities. An additional 34 are currently under construction.

Prior to this, two prominent examples stand out. In 2018, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi inaugurated the Church of the Martyrs of Faith and Homeland in al-Our, a village in Upper Egypt, to honor the Copts beheaded by ISIS in Libya. And in 2019, he consecrated the massive Cathedral of the Nativity of Christ in what will become the new administrative capital of Egypt, alongside its central mosque.

This is in addition to restoration work at 16 historic Coptic sites and further development of the 2,000-mile Holy Family Trail, tracing the traditional map of Jesus’ childhood flight from King Herod.

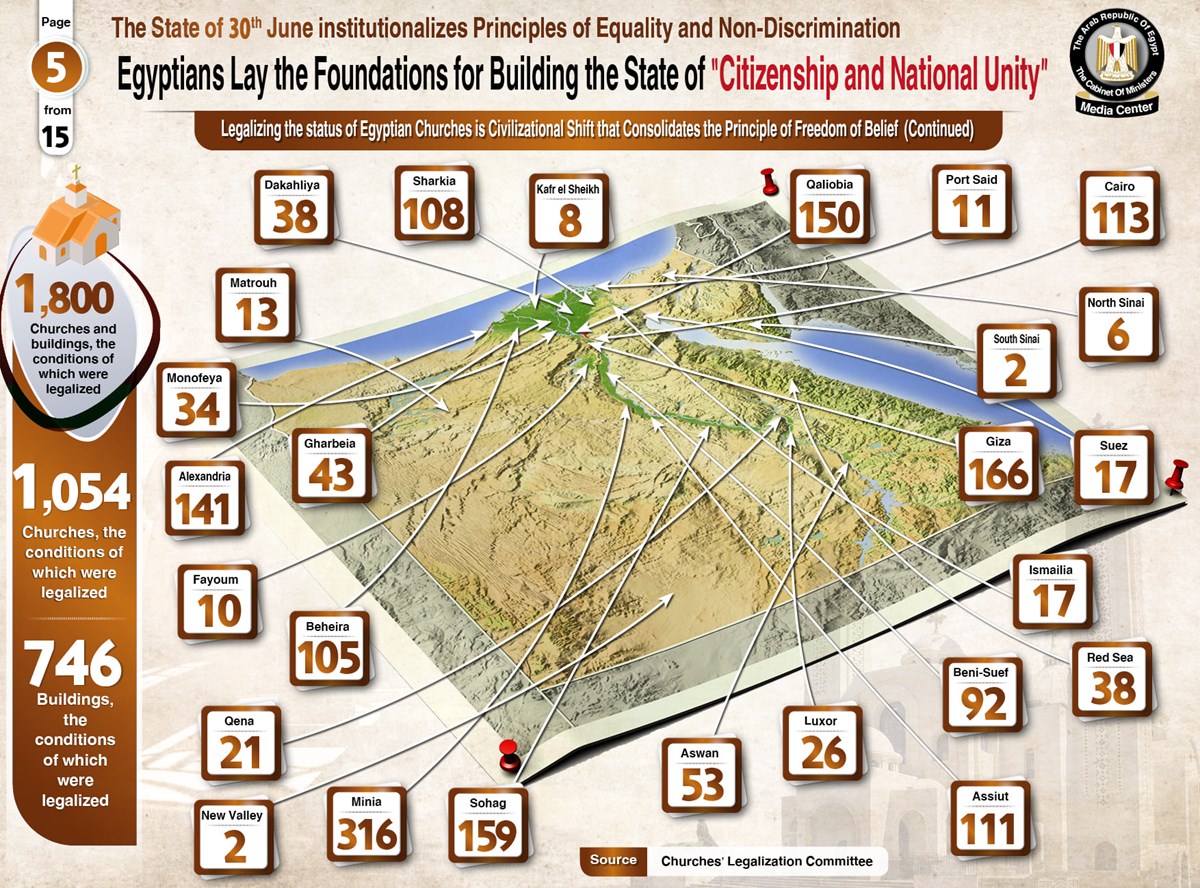

And since the 2018 implementation of a 2016 law to retroactively license existing church buildings, a total of 1,800 have now been registered legally.

An Egyptian government infographic depicting recent progress in legalizing Christian churches.

Persecution has long been a term applied to Copts in Egypt, ranked No. 16 on the Open Doors 2021 World Watch List of nations where it is hardest to be a Christian.

But shortly after the mufti’s fatwa, which restated a ruling last given in 2009, the Grand Imam of al-Azhar gave a pronouncement of his own.

Representing Sunni Islam’s most prominent religious institution, Ahmed al-Tayyeb said that the terms dhimmi (the protected but second-class Christian or Jewish community in a Muslim state) and jizya (the tax paid to achieve such status in lieu of converting to Islam) no longer have any relevance in Egypt.

While the jizya tax was formally abolished in 1855, the continued use of these terms must give way to the concept of citizenship.

Christians, he said, have the same rights and responsibilities as Muslims.

Both rulings came under fierce criticism in social media.

So while other issues—such as discrimination against Copts in professional soccer—remain before full religious equality is achieved, religious freedom advocates have noted the improvements.

“There has been a marked shift in the way Egypt recognizes these challenges,” said Nadine Maenza, a commissioner with the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF). “Sisi has publicly acknowledged them and made incremental changes.”

Others, however, note a different reality beneath the rhetoric.

“There are many things at the top that [Sisi] has done that are encouraging,” said French Hill, a Republican representative from Arkansas who has introduced bipartisan resolutions supporting Coptic Christians. “But it hasn’t changed the challenges on the street.”

Two high-profile cases provide an example, highlighting the distance between the initial euphoria of the Arab Spring and the failure of youthful exuberance to fully transform the long-ingrained habits of both state and society.

Ramy Kamel, a 33-year-old activist, was once dodging tanks near Tahrir Square, protesting for Coptic equality. Ten years later, he is in jail for “spreading false news” about Coptic discrimination, and “financing a terrorist group.”

Soad Thabet, a 74-year-old Coptic grandmother, was in the Upper Egyptian village of al-Karm, minding her own business. Now she is fighting for justice after having been stripped naked and paraded through town, with her Muslim attackers acquitted.

These examples show that the term persecution remains “appropriate,” said Kurt Werthmuller, a USCIRF policy analyst specializing in Egypt.

In 2016, rumors surfaced that Thabet’s son was having an affair with a Muslim woman. Mobs formed and torched several Coptic homes in her village, 200 miles south of Cairo, before abusing Thabet.

Sisi publicly decried the violence and pledged justice on her behalf.

Three villagers were initially sentenced to 10 years in prison. But last month in advance of their appeal, a local “reconciliation committee” convinced Coptic villagers to drop the charges.

“Who can guarantee us and our families safety and protection if [they] are sentenced?” the Coptic newspaper Watanireported the villagers said. “We just want to live in peace.”

Thabet did not drop the charges, but the defendants were acquitted anyway.

Werthmuller lamented the “culture of impunity” that characterizes the regular use of these traditional councils. The villagers also reported they could have accepted the incident if it was just a matter of their homes being burned—as opposed to the shame of nakedness.

But this, said the analyst, just proves the point.

“No community should ever have to say this,” said Werthmuller. “No person should have to accept mob attacks as ‘just the way it is.’”

But speaking generally to the topic of mistreatment by the state, Egypt’s Pope Tawadros, head of the Coptic Orthodox Church, denied the implication.

“In Egypt there are 5,000 villages. It happens that in some of them people act recklessly,” he stated. “I categorically reject the definition of ‘persecution.’”

Similarly, Ramez Atallah, general secretary of the Bible Society of Egypt, stated there are surprisingly few problems among an Egyptian population of 100 million, many of whom have set traditions.

“With a large network of 230 staff scattered across the nation, I don’t hear stories of persecution,” he told CT. “We at the Bible Society have not experienced anything of this nature.”

And Andrea Zaki, president of the Protestant Community of Egypt, praised Sisi’s overall efforts to “promote citizenship and equality.” Of the recently legalized churches, 310 belong to his denomination.

The Mediterranean city of Alexandria—once home to the famous Didascalium that trained Origen and other church fathers in theology—is witnessing new church growth. The downtown St. Moses the Black Church is being dramatically enlarged. And churches are under construction in a new development planned near the ancient catacombs where Christians once hid from their Roman persecutors.

“There is freedom to license and renovate churches,” said Zahraa Awad, a Muslim tour guide in the city. “Along with mosques, schools, and hospitals, they are required for every new neighborhood.”

But the gains go beyond religion into politics. Since the 2014 constitution established a quota, elected Coptic parliamentarians have increased from 5 to 31 in Egypt’s House of Representatives and from 15 to 24 in its Senate. And since his reelection in 2018, Sisi installed two Copts as governors of Egypt’s 27 regions, the highest total in modern history.

Furthermore, Atallah mentioned the disproportionate level of wealth in the Coptic community, as well as the benefits of a conservative culture that values the moral principles of the monotheistic religions.

He reflected on 40 years of ministry, comparing it to his earlier life in Canada.

“I feel safer in Egypt as a person, freer as a Christian, and like I belong,” said Atallah. “The specific persecution of Christians by the state is a misnomer—not something you can say now.”

Ramy Kamel might disagree.

A founding member of the Maspero Youth Union of mostly Coptic activists, Kamel later turned to research and documentation of ongoing inequality and attacks against Christians. An Egyptian media outlet named him one of the decade’s “Most Influential Figures in Egyptian Politics.”

In 2019, Kamel presented a dossier to Egyptian Americans scheduled to meet with US State Department and congressional officials. Later he began receiving warnings from the government and was arrested in November, five days before joining UN officials at a conference in Geneva on minority rights.

Kamel has spent the last year in pretrial detention, much of it in solitary confinement. His lawyers state he has been tortured.

One Christian leader, requesting anonymity, tried to put it in context.

Rather than an example of persecution against Copts, Kamel’s case shows official sensitivity to any criticism—whether from Muslim or Christian. Because of continued attacks by groups like the Muslim Brotherhood, the government interprets such activity as undermining the stability of Egypt within a very volatile region.

Liberal groups suffer also. Activists from the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR)—including Patrick Zaki, a Copt—and journalists from the Mada Masr online newspaper have also been detained.

“It is difficult to know how to be critical without being against those in charge,” said the source. “Christians who are not wise in expressing their concerns are seen as a threat and often treated more harshly than necessary.”

USCIRF, Coptic Solidarity, and 21Wilberforce are among the many organizations that call for Kamel’s release.

They are not the only ones.

“The arrest of Ramy Kamel, a patriotic Egyptian and pure human rights advocate,” stated Emad Gad, a Coptic member of parliament, “is a shocking decision producing negative repercussions for the image of the Egyptian regime.”

The image is suspect in other ways, said Sam Tadros, senior fellow at Hudson Institute’s Center for Religious Freedom. His grades for the government mirrored its infographic.

For appointments, a B. Two Coptic governors is an achievement.

But there are zero Copts in the higher ranks of the intelligence and security services, sending a message that they are not to be trusted.

For church building, a C. New churches in new cities are commendable.

But only one has been built in an already populated area: the Libyan martyrs’ church. And Sisi’s decree was met with such opposition that it had to be moved to the outskirts of the village.

And for sectarian attacks, an F.

“Church leadership is not completely free to speak its mind,” said Tadros, the Coptic American author of Motherland Lost: The Egyptian and Coptic Quest for Modernity. “And official inaction [in deference to local reconciliation committees] shows best that there is persecution.”

Tadros, Werthmuller, and Maenza presented their remarks as panelists on a webinar hosted by In Defense of Christians. While each one remarked on Sisi’s positive rhetoric and the important message it sends to the state, they also undermined other aspects of the government’s infographic.

The educational curriculum does promote tolerance, said Tadros, but it omits Coptic contributions to Egypt’s history, skipping from the pharaohs to the Muslims.

The church-building law was long awaited and has helped registration, said Werthmuller, but it moves at a “glacial pace.” The 1,800 approved churches and church-related buildings are only one-third of the 5,415 total submissions. (The 310 Protestant approvals come from a total of 1,070.)

The constitution does establish safeguards for religious freedom, said Maenza. But Baha’is, unorthodox Muslims, and converts from Islam continue to face discrimination.

So are the changes real?

Perhaps Egypt is trying.

Coptic plaintiffs have won the right to apply Christian inheritance laws, having previously been subject to Islamic sharia. A prison has been opened to the foreign press. And the death penalty was upheld for an ISIS-inspired murderer of a Coptic Orthodox priest, whereas in years past such criminals would often be classified as mentally unstable.

Finally, Egypt’s public prosecution appealed the acquittal of Thabet’s attackers.

But unlike the international outcry last month that won the release of three EIPR activists—but not Zaki—there has not yet been enough clamor for Kamel.

“Egypt is a massive and complicated country, and change comes very slowly,” said Maenza. “But this is no excuse.”

Additional reporting by Emma Hodges

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month