A Protestant mother. A Shiite son. A plea for vengeance on his killers.

But unlike many responses to political martyrdoms in Lebanese history, she yields it to God.

Last month in the Hezbollah-controlled south of Lebanon, unknown gunmen shot Lokman Slim in the head. It was a targeted assassination of a man dedicated to the hope that his small Middle Eastern nation might overcome sectarian divisions.

He was his mother’s son.

“I will not go and kill them, but ask God to avenge him,” said the grieving 80-year-old, Selma Merchak. “This comes from my faith in God as the great authority.”

But her next response reflects the family’s—and Lebanon’s—complex religious identity.

“And as it says in Islam: Warn the killer he will be killed, though it tarries.”

Born in Egypt, Selma’s Protestant lineage traces back to her grandfather in Syria, who found Christ through the preaching of the first wave of Scottish missionaries to the Middle East. As a child, she attended the American School for Girls—now Ramses College—founded in 1908 by American Presbyterians.

The family attended Qasr el-Dobara Church, located in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. And Selma continued in the Protestant educational heritage, graduating with a degree in journalism from the American University in Cairo, which by then had become a secular institution.

The Merchak family mixed freely in an Egyptian upper class that was open to all religions, vacationing often in Lebanon’s mountains. But in the chaos of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalizing of the Suez Canal, in 1957 Newsweek relocated its regional headquarters to Beirut, and Selma went with it.

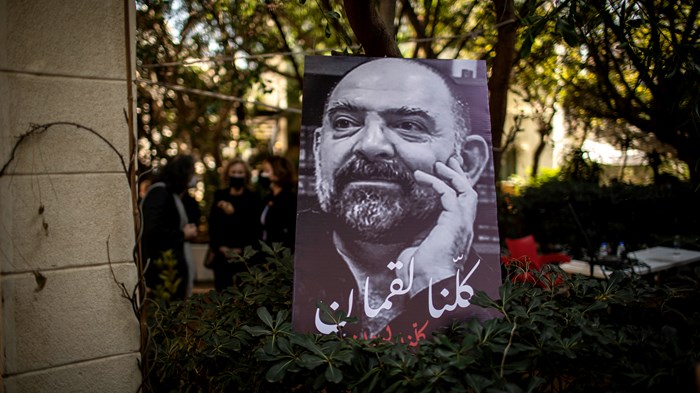

Selma Merchak, at her son Lokman Slim's funeral

She reconnected with Muhsin Slim, her childhood friend from the family vacations. The Slims were an influential Shiite family known for its good relations with the Lebanese Christian elite. Muhsin’s father served as a member of parliament in the 1960s, and during the civil war advocated against the use of Lebanon as a staging ground for the Palestinian armed struggle against Israel.

Now a lawyer, Muhsin married Selma shortly after her arrival in Lebanon. Her Egyptian accent was the toast of the town, aiding the political career of her parliamentary husband.

While Muhsin would only “pray in his heart,” Selma said, she worshiped on-and-off at the National Evangelical Church in Beirut, the oldest indigenous Protestant congregation in the Middle East.

Lokman, their second of three children, was born in 1962. Registered as Shiites within Lebanon’s sectarian system, Muhsin and Selma raised them to be moral, but to make up their own minds about religion.

Statues of Buddha were part of the décor of their 150-year-old home. On property located in what was once known as “The Plain of the Christians,” Muhsin’s grandfather raised silkworms and exported their product to France.

“The absence of a formal faith was a challenge for us,” said Lokman’s younger sister Rasha, who described a childhood hurt when queried about her sect. “Were we Muslims, Christians, or Buddhists? I wanted to know what we believed about God.”

Lokman, however, was more at ease with an amorphous spirituality. The children attended a French Catholic school, and in 1982 he left Lebanon to study at the Sorbonne in Paris. Two years after graduation, in 1990 Lokman founded Dar al-Jadeed publishing house with Rasha, introducing new and controversial works to society, including the books of Iran’s reformist president Mohammad Khatami.

By then, however, the neighborhood had transformed into a plain of Shiites, as the war years forced many from the south and Bekaa Valley into Beirut. Villa Slim, as their home was known, became an oasis of green as surrounding farmlands were sold and turned into cramped, lower-income apartments.

Hezbollah gained political control.

Lokman, meanwhile, stayed true to his upbringing. In 2004, he and his German wife, Monika Borgmann, filmed the award-winning Massaker documentary, about the 1982 slaughter of Palestinians in Beirut’s Sabra and Chatilla refugee camps.

Researching the film led to the discovery that Lebanon did not have a national archive, from which it could build a shared history among its periodically at-war sects.

So they built one themselves—in the family home.

One of the central exhibits of the Umam (peoples in Arabic) Documentation and Research Center is a collection of photographs of Lebanese who went missing during the civil war. Presumably killed or carted off to Syrian prisons, the pain of their families is now known—in truth, re-experienced—by Selma.

“If Lokman had died an old man like Muhsin, we could accept it as God’s will,” she said, as she did when her husband passed away after 46 years of marriage.

“This pain is different, and criminal.”

But it is not unfamiliar. One of Muhsin’s clients was Kamal Mrou, founder of the al-Hayat and Daily Star newspapers. A family friend, Mrou was assassinated in 1966 due to his opposition to Nasser-led Arab nationalism.

Lokman is one more victim, in a long line.

Selma hopes the courts will achieve justice.

Immediate suspicion for his killing fell on Hezbollah, which denied responsibility and condemned his murder. Indeed, Lokman’s archiving work was an implicit critique of all of Lebanon’s leaders. In 2005 he made it explicit, leading the Hayya Bina [Arabic for Let’s Go] movement to mobilize greater nonsectarian participation in elections.

Even so, Lokman was unusual as an outspoken Shiite critic of the Iran-backed entity. In 2019, during a massive popular uprising against the entire political class, Villa Slim was covered in graffiti labeling him a traitor.

“‘Do you scare me with death?’” Rasha recalled her brother saying, comforting her with the saying of Hussein, the seventh-century grandson of Muhammad and an extolled Shiite martyr.

“Lokman was not afraid of death.”

At the funeral, Selma, Monika, Rasha, and the rest of the family held aloft black signs with white Arabic lettering: No fear.

Others, however, are at least nervous.

“Hezbollah may not be the killer, but they created the environment,” said a Shiite professor at a Lebanese university, who requested anonymity.

“All Shiite activists have felt the hunch they could be a target. But you have to learn to live with it.”

Hezbollah emerged in 1982, fighting the Israeli occupation in southern Lebanon during the civil war until its withdrawal in 2000. In 2005, the militia entered politics, allying with Michel Aoun, the Maronite Catholic general—now the nation’s president—who leads the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), the largest Christian party.

Hezbollah has been pragmatic in politics. But the professor was critical of its overall mentality of “us versus them, good versus evil.”

In contrast, he praised Selma’s continued faith as something “remarkable.” Today, he said, the norm is that a Muslim man will ask a Christian wife to convert to Islam.

But with Lokman, both faiths were embedded in him, sincerely.

Sheikh Mohamed al-Amili, a Shiite, agreed—speaking from a safe house in the Sunni Muslim mountainous region of the Chouf. In 2013, Lokman helped him establish Godly Without Borders, a group to move interfaith dialogue toward greater practical benefit to society.

“Some people want to paint Lokman as an atheist or nonbeliever,” he said. “But what interested him was the spirituality of religion, not its appearances.”

Frustrated by Lebanon’s sectarianism, some activists have turned against religion entirely. But this can fuel accusations by opponents that their colleagues have also denied God.

Amili, however, highlighted the saying of Muhammad that a Muslim is one “from which the people are safe, from his tongue and hand.” This fully characterized Lokman, and clearly not his opponents.

Their interfaith message resonated during meetings in cosmopolitan Beirut, Sunni-dominated Tripoli, and the heterodox Druze Muslim communities of the Chouf, Amili said.

But their group found no foothold in Hezbollah’s southern regions.

“We want people to have a pure faith in God,” said Amili, “not just a religion that is related to politics.”

In sectarian Lebanon, this is a difficult proposition.

For years, Shiite Lebanese were marginalized politically and economically. They bore the brunt of Israeli occupation. Even if they do not share Hezbollah’s ideology, many Shiites appreciate the strength given to their community.

By contrast, Christians and Sunni Muslims are internally divided. Those who blame Hezbollah for Lokman’s murder say that as Shiites also grow frustrated with the ruling political class, the assassination is a warning against dissent.

Others label it a warning to the United States, as the nation jockeys with Iran over the nuclear deal and fallout from the killing of Qassem Soleimani. The Iranian commander’s picture is plastered everywhere on the road to the airport through Shiite neighborhoods of Beirut. One superimposes his image over a torn US flag.

“We are called ‘Shiites of the [US] Embassy,’” said Amili.

At the funeral, the American ambassador to Lebanon came to Villa Slim to pay her respects.

“We all were robbed of a great man,” said Dorothy Shea, pledging to continue the partnership with his organizations.

“[Lokman] was tireless and relentless in his pursuit to reconcile Lebanon’s people, and to promote freedom and inclusion.

“So, like him, let us not be deterred.”

Rasha appreciates these words. But Shea was only one of several ambassadors present.

“I refuse the propaganda of the killers who accuse him of working for the embassy,” she said. “Lokman was respected by everyone as an analyst, while Hezbollah is the first to declare their coverage by Iran.”

But this was not the only controversial element of the funeral.

“This house has given much to Lebanon, and today offers and sacrifices its blood for its promotion,” said Amili in his remarks.

A fellow Shiite, Sheikh Ali al-Khalil, led the Muslim prayers. But after receiving fierce social media criticism for attending, he apologized, saying his political orientation [implying Hezbollah] was well known.

Meanwhile, the Christian component of the service included the chanting of “The Mother of Sorrows,” a Maronite hymn to the Virgin Mary. Traditionally sung only on Good Friday, its use at a funeral was met by strong criticism, including by the bishop of Beirut and by supporters of FPM.

Selma, however, had the most poignant testimony.

“If you want a homeland, you must cling to the principles for which Lokman was martyred,” she said.

“The burden will weigh heavy on you. [But] stay away from weapons; those have taken away my son.”

The funeral arrangements placed a picture of Lokman in the family garden, surrounded by wreaths laid in his honor. Every detail was planned meticulously by his loved ones.

“Some people want us to be atheists, others were offended by our interfaith service,” Rasha said. “But do not put walls between your God, and ours.”

Could this be a message also to Lebanon’s Protestants?

It was not intended to be—but might apply.

“Many evangelicals would leave their sectarian areas to preach Christ or open new house churches,” said Nabil Habibi, a pastor in the Nazarene church, who was invited to participate in the funeral.

“But many might not come here, not wanting to die for a political cause.”

He himself was nervous. Hezbollah would be watching, but he felt his clerical collar would protect him.

And it was important to take a stand against “the forces of darkness.” His presence at the funeral would join in the message that it is not right to kill those you disagree with.

It was also a message of national unity. All of Lebanon’s sects were invited, and Habibi wanted to ensure that Protestants were present.

Habibi was asked to offer a prayer, but in the end only the Shiite and Maronite invocations were spoken. He would have commended Lokman’s bravery.

“God, we have come here seeking justice, because your ears are not closed to the cries of the oppressed,” Habibi had prepared.

“Help this family in their grief. Forgive those who killed him.

“Show them your mercy, and bring them out of darkness.”

Martin Accad, associate professor of Islamic Studies at Arab Baptist Theological Seminary in Beirut, also attended the funeral. He did not know Lokman personally, and expected a secular event.

He was surprised it was so religious—but sensed this was how his family remembered him.

“Selma evidently has a faith commitment, and raised a son who valued truth and reconciliation,” he said. “It reflects her mainline Protestant ethic, which it seems Lokman fully embraced.”

A quiet but clear distinction exists between the two wings of the Supreme Council of the Evangelical Community in Syria and Lebanon. Though there is overlap, Presbyterians and Congregationalists tend toward ecumenical engagement, while Baptists and Pentecostals seek out converts. Yet both are engaged in social work, with friendly personal relations.

But Accad cautioned the evangelicals who might be wary of participating in such an interfaith event. Jealous for the gospel, they risk mirroring the same reactions as the Shiites and Maronites who spoke their offense.

And where mixed communities are the reality in society, evangelicals face the choice of staying in their corner—or joining with others to contribute positively.

Too few have reached out to the Shiites.

Imam Musa al-Sadr, Accad recalled, said that the voice of Jesus could be heard in the call of the minaret. The civil war leader’s “Movement of the Deprived” sought Shiite equality in Lebanon.

But after Sadr’s disappearance in 1978, the movement increasingly went militant. And later, its secular character gave way to Hezbollah’s religious ideology.

“The murder of Lokman is a picture of lethal sectarianism,” Accad said. “But Selma’s story illustrates the influence of evangelicals, in a multifaith society.”

Her Christian commitment helped shape Lokman for Lebanon.

The family, meanwhile, is both reeling and resolute.

“I want to believe in a just God,” said Rasha, who regularly reads from the Bible. “But all I see is injustice among the religions.”

“My mother says, ‘Pray.’

“I said, ‘You pray.’

“Lokman’s death is an eclipse of God, and I don’t have any answers.”

But one answer is clear.

“This project will never be silent,” said his widow, Monika. “They can kill Lokman, but they will not kill his ideas.”

And the family home, Selma reminds her neighbors, is older than Hezbollah.

“I will never close these doors and stop receiving people,” she said.

“If they want to kill us, let them tell their God that they are killers.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misattributed a funeral quote (“This house has given much to Lebanon…”) to Sheikh Ali al-Khalil. It was Sheikh Mohammed al-Amili who gave that remark.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month