Sorry Job, Epicurus, Augustine, and Hume: On the “problem of evil,” most Americans don’t think much of God’s role.

Long before Rabbi Harold Kushner’s When Bad Things Happen to Good People got Americans talking about theodicy in the 1980s, these famous thinkers wrestled with explaining why an all-loving, all-knowing, and all-powerful God would allow suffering.

Amid the pandemic and its 5.2 million reported deaths, the Pew Research Center surveyed 6,485 American adults—including 1,421 evangelicals—in September 2021 about how they philosophically “make sense of suffering and bad things happening to people.”

The most common explanation: It happens.

“Americans largely blame random chance—along with people’s own actions and the way society is structured—for human suffering, while relatively few believers blame God or voice doubts about the existence of God for this reason,” concluded Pew researchers in a new study released today.

Yet many Americans do see purpose in pain, as researchers noted:

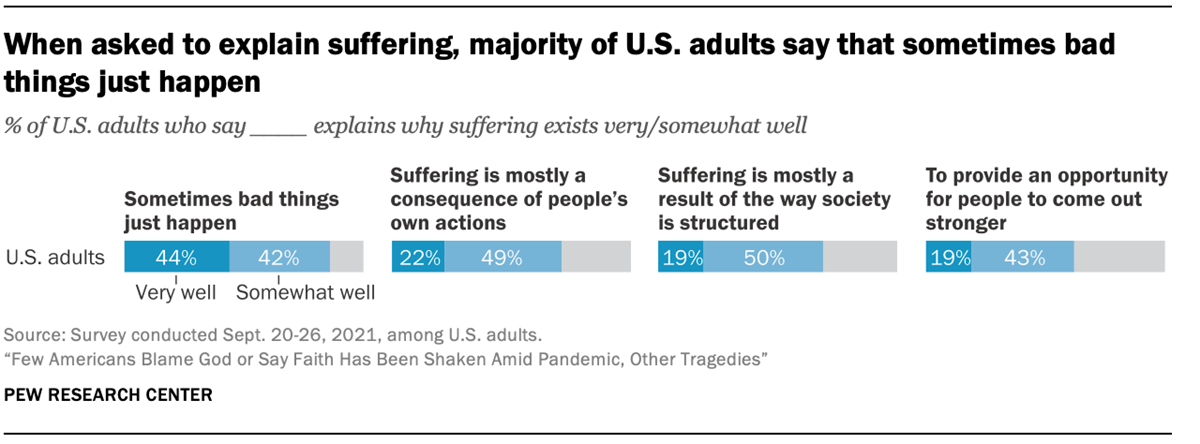

The vast majority of U.S. adults ascribe suffering at least partly to random chance, saying that the phrase “sometimes bad things just happen” describes their views either very well (44%) or somewhat well (42%). Yet it is also quite common for Americans to feel that suffering does not happen in vain. More than half of U.S. adults (61%) think that suffering exists “to provide an opportunity for people to come out stronger.” And, in a separate set of questions about various religious or spiritual beliefs, two-thirds of Americans (68%) say that “everything in life happens for a reason.”

Among the survey’s main findings:

- 7 in 10 American adults agree that suffering is “mostly a consequence of people’s own actions.” Yet also 7 in 10 agree that suffering is “mostly a result of the way society is structured.”

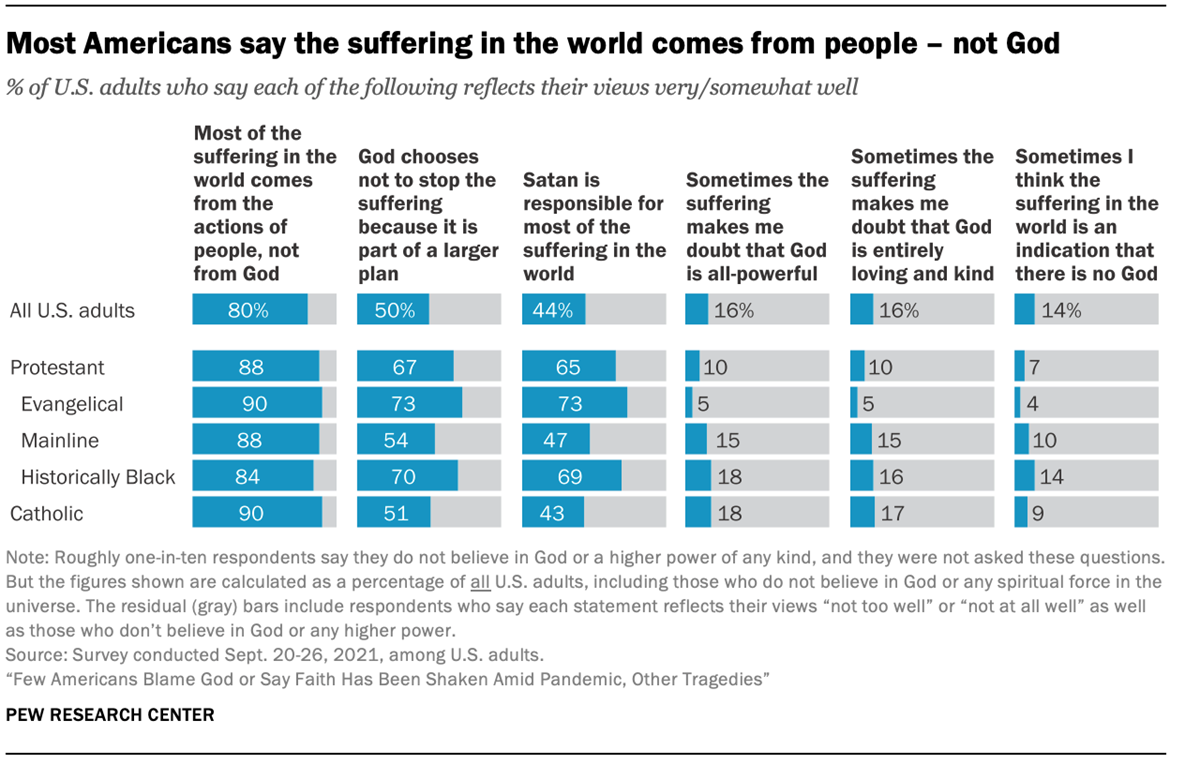

- 8 in 10 are believers—either in “God as described in the Bible” (58%) or in “a higher power or spiritual force” (32%)—yet say most suffering “comes from the actions of people, not from God.”

- 7 in 10 believe human beings are “free to act in ways that go against the plans of God or a higher power.”

- 5 in 10 believe God allows suffering because it is “part of a larger plan.”

- 4 in 10 believe Satan is responsible for most of the world’s suffering.

- Less than 2 in 10 say they have doubted God’s omnipotence, goodness, or existence because of suffering.

While members of evangelical and historically black Protestant churches are nearly equal in their views that God has a larger plan for suffering (73% vs. 70%) and of Satan’s responsibility for suffering (73% vs. 69%), black Protestants were three times as likely as evangelicals to say suffering makes them doubt that God is all-powerful (18% vs. 5%), doubt that God is all-loving (16% vs. 5%), or doubt that God exists (14% vs. 4%). The views of mainline Protestants and Catholics are similar to black Protestants.

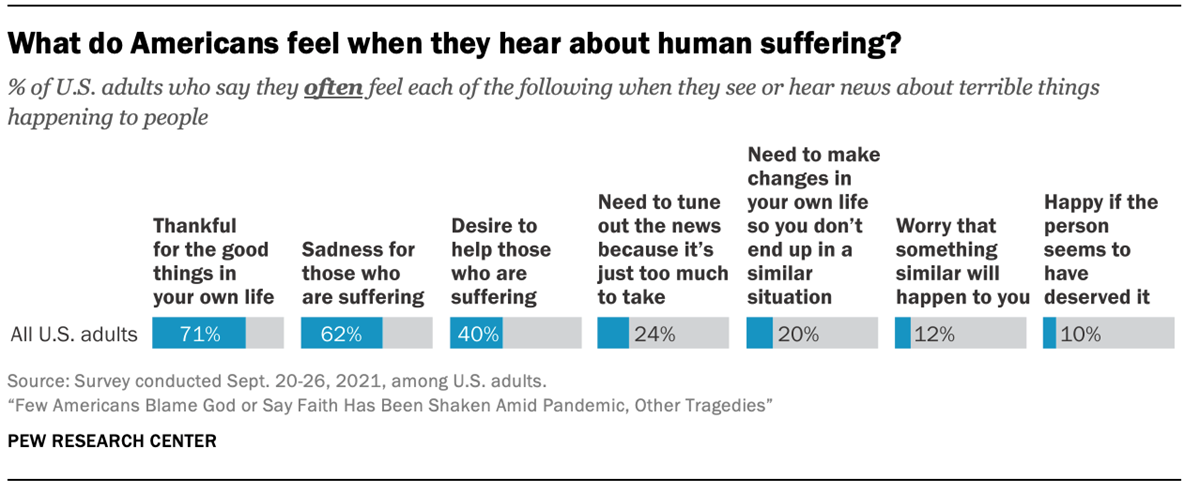

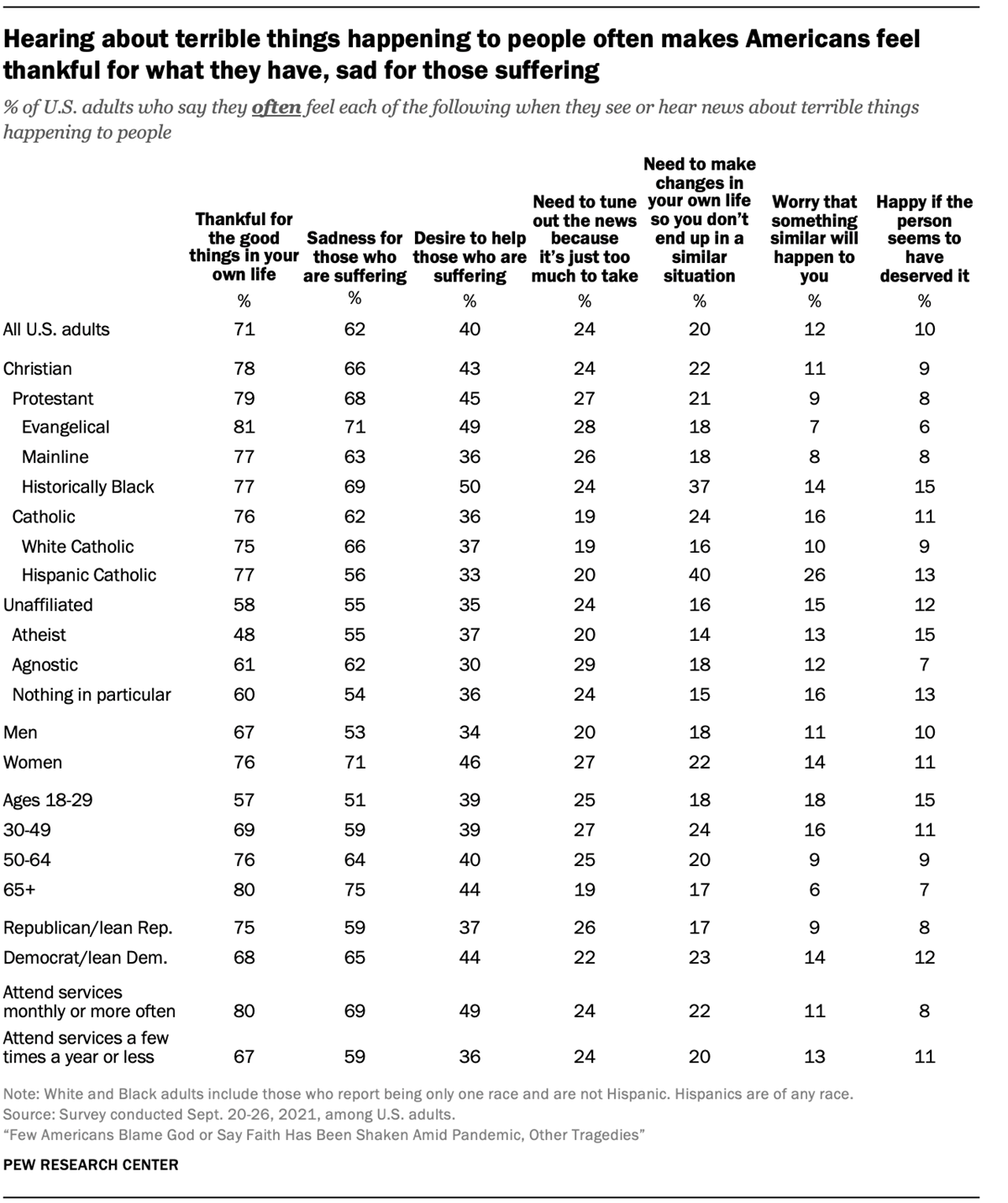

Finally, when it comes to emotional responses, Pew found:

- 2 in 10 American adults get angry with God because of suffering.

- 2 in 10 believe suffering is punishment from God.

- 1 in 10 feel schadenfreude, or happy when bad things happen to “bad people.”

The problem of evil is “the hardest thing to confront as a Christian philosopher,” Alvin Plantinga told CT after winning the Templeton Prize in 2017 for his influential work to bring theism back into the study of philosophy.

“It’s really hard to understand, even after thinking about it for many years, why God would permit so much evil in the world. You have to wonder, ‘Why does God permit that?’” said the Christian philosopher in a podcast interview. “I think we don’t know. I don’t think there’s a good answer to that. There are lots of suggestions people have made, theories people have tried out. But I don’t think any of them are very satisfactory. At the end, this is a puzzle.”

Prior to the pandemic, CT examined why viruses don’t disprove God’s goodness.

The Pew survey released today also asked Americans 20 questions about heaven and hell and other afterlife topics.

Editor’s note: This post will be updated.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month