African Americans are among the most devout groups in religion research, often outranking other demographics in areas like religious practice, attendance, and belief.

As a result, some predicted that young Black adults would resist the moves away from faith seen among white millennials.

Even with all the shifts in the faith landscape over the past several years, Black Americans remain more religious than other groups and more likely than the average American to stay in the tradition they were raised in, according to a massive report released by Pew Research Center last year.

But black “nones” are growing. With 3 in 10 adults in the US claiming no religious affiliation on surveys, the rise of the nones has touched every corner of American society.

Over more than a decade, the share of Black Americans who say that they have no religious affiliation has risen more dramatically than whites, Hispanics, or Asians.

But looking beyond that statistic, we see a much more nuanced view of Black religion in the United States.

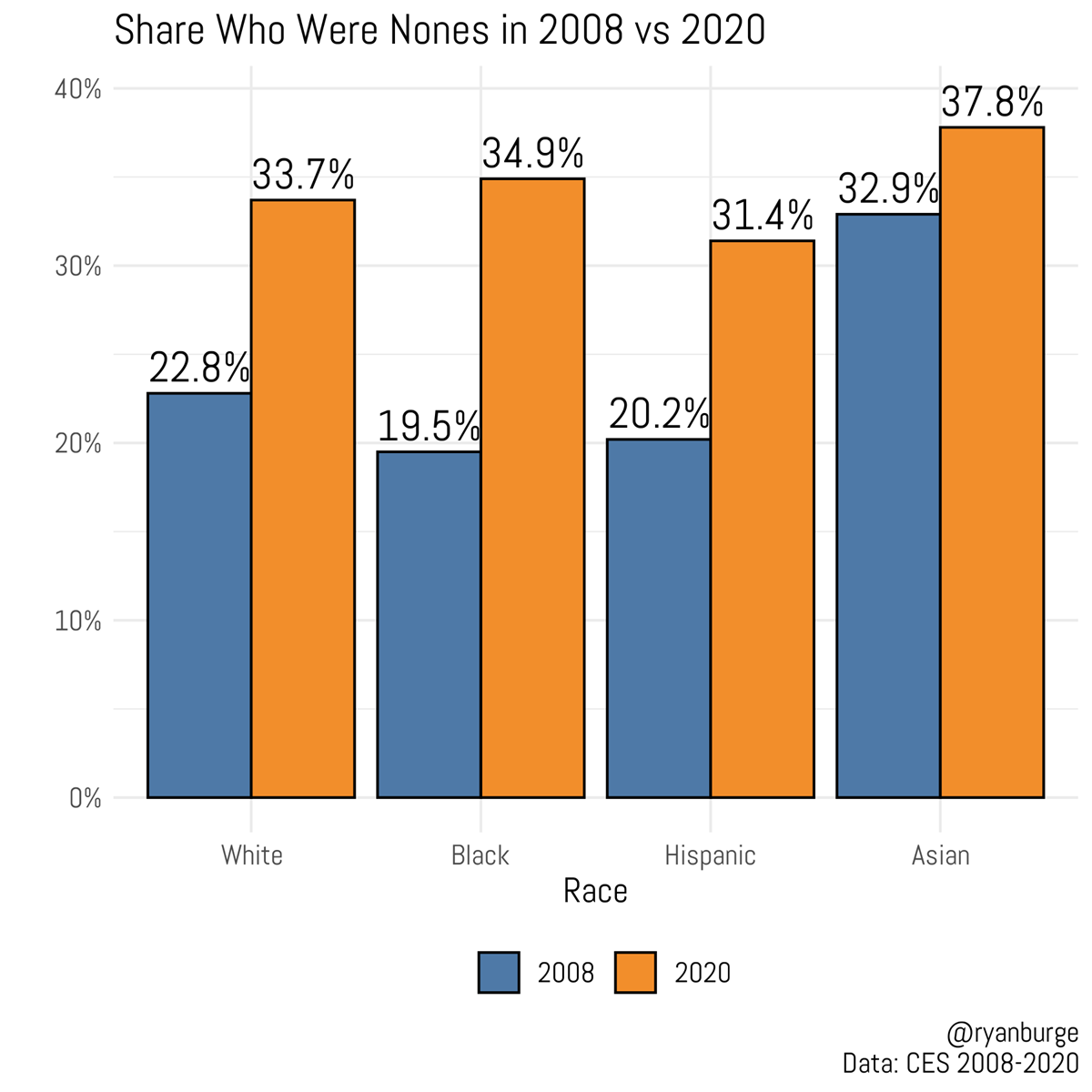

In 2008, 22 percent of all Americans who participated in the Cooperative Election Study indicated that they were atheist, agnostic, or described their religion as “nothing in particular.” Just 12 years later, the share of nones rose to just over 34 percent. When that rise is tracked across different racial groups, different patterns emerge.

For instance, white respondents tracked the national average nearly perfectly, with 23 percent nones in 2008, rising to 34 percent by 2020. Among Hispanic respondents. There was an increase of 11 percentage points, but for Asians—who already had the highest levels of religious unaffiliation—it was much more modest at just about 5 percent.

Among African Americans, the increase in the share of the nones was much larger, more than 15 percentage points. In 2008, African Americans were the least likely to be nones (19.5%), but by 2020 they were more likely to say that they had no religious affiliation than white or Hispanic respondents (34.9%).

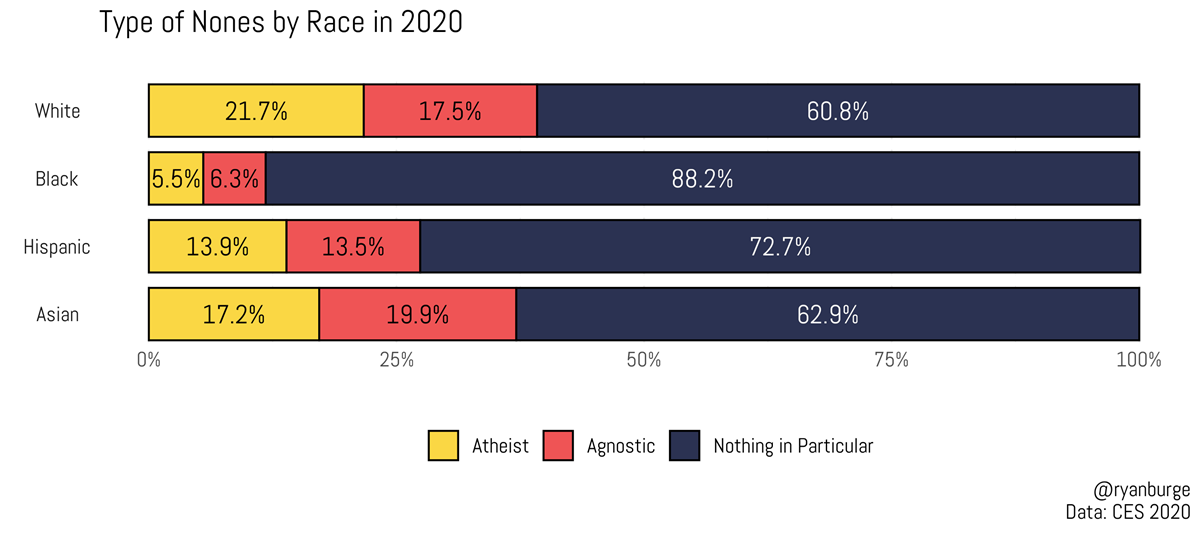

But beyond that top-level statistic, the story among African Americans is much more subtle and nuanced. As previously mentioned, three response options are combined to make up the nones: atheists, agnostics, and those who say that they have no religion in particular.

When the types of nones are calculated for each racial group, a much different picture emerges. While the nones have gained the most ground among African Americans, that does not mean that there are many more Black atheists and agnostics than there were in 2008.

In fact, among Black nones, just 6 percent of them identify as atheist and another 6 percent say that they are agnostic. That means that nearly 9 in 10 Black nones are nothing in particular. That’s much higher than any other racial group.

For instance, just 61 percent of white nones are nothing in particular, 63 percent of Asians, and 73 percent of Hispanics. Clearly, when African Americans leave religion behind, they are very reluctant to embrace the labels of atheist or agnostic.

There’s a chapter in my book about the religious unaffiliated titled “All Nones Are Not Created Equal” about how different those three groups are really based on a number of demographic factors, but one stands out. Among those who said that they were atheists in 2010, just 3 percent identified with a religion in 2014. Among agnostics, it was 6.5 percent who embraced a religious tradition. For nothing in particulars, it was nearly 25 percent.

Thus, the data indicates that Black nones have a stronger faith background and are much more likely to embrace religion in the future than nones of other racial groups.

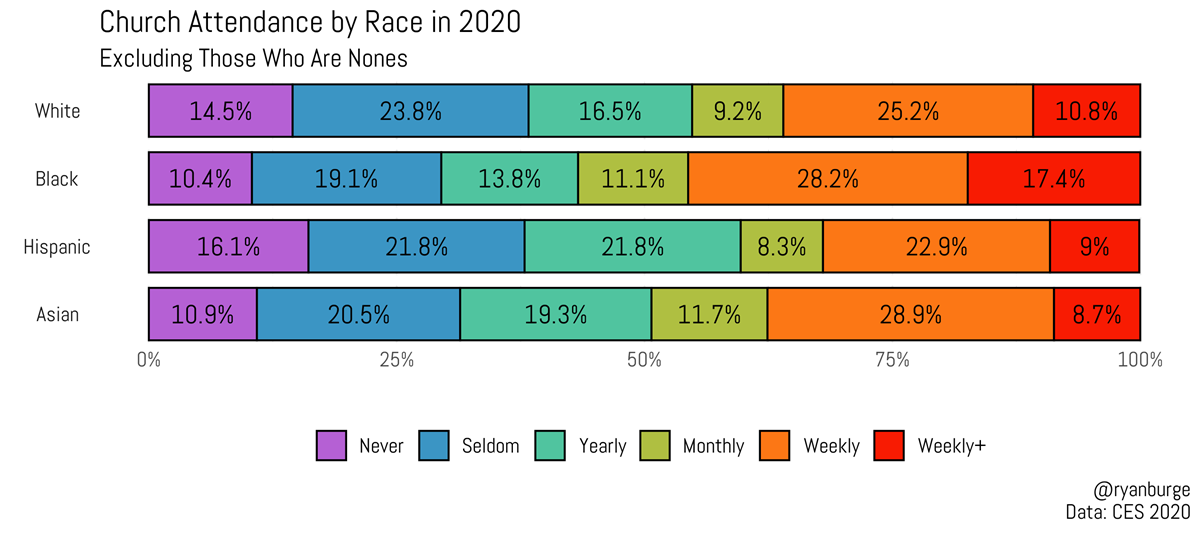

Despite rise of religious unaffiliation, Black Americans who still identify with a religious tradition are staying faithful. They continue to report much higher levels of church attendance than other races.

For instance, in 2020, nearly 46 percent of religious Black people describe their church attendance as weekly or more than once per week. For white respondents, just 36 percent attended weekly or more. For Hispanics that percentage was 32 percent and for Asians it was 38 percent. On the other end of the spectrum, less than 30 percent of Black respondents said that they attended church less than once per year. That’s nearly 10 points lower than whites in the sample.

While the share of the nones has nearly doubled in the past 12 years among Black Americans, there’s still plenty of evidence in the data that they are more open to religion than other racial groups.

In 2020, just 2 percent of all African Americans said that they were atheists, and another 2 percent were agnostics, compared to 31 percent who said that they had no religion in particular.

As previously mentioned, “nothing in particulars” are 4 to 8 times more likely to come back to religion over time compared to atheists and agnostics. That means that many of them may return to religion over time. And among those who still identify with a religious tradition, Black Americans are more active in their religious communities than any other racial group.

Even in an age of rapid secularization, the Black church still plays a crucial role in the lives of African Americans throughout the US. For Black pastors, the mission field is incredibly ripe, and many are heeding this call.

The North American Mission Board has worked in partnership with the SBC’s National African American Fellowship with the SBC’s National African American Fellowship to plant churches in underserved African American communities across the United States, and the first fruits of those efforts are already beginning to emerge. New efforts by Crete Collective and Dhati Lewis’s forthcoming BLVD are also turning attention to such communities.

Jude 3 Project, an apologetics ministry among Black Christians led by Lisa Fields, has a discussion series called “Why I Don’t Go,” engaging and listening to African Americans who have left the church.

“Classical and traditional apologetics goes a lot to proving the existence of God. When you know the Black context, you realize most Black people believe that a God exists or a higher power exist,” Fields said in a podcast interview last year.

“Black atheism is growing, but it’s still a minority of Black people. So we have to figure out what black people are navigating, what are the challenges, and meet them there.”

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month