Over the past several decades, American evangelicalism has moved away from the religious labels, symbols, and buildings that used to define church.

Many newer churches don’t contain stained glass, crosses, or traditional sanctuary setups. They tend to adopt contemporary names, leaving out denominational labels or other religious language. Along with those shifts, churchgoers have changed the way they speak about their faith; think of phrases like “It’s is not a religion; it’s a relationship.”

These trends have had a real impact on how younger people understand their religious identity. Evangelical Protestants have been debating for years over the definition and usefulness of the “evangelical” label. Now, it appears “Protestant” may be losing its place too.

New research shows that a significant portion of Americans no longer attach to the word “Protestant” the way older Americans have for generations—a finding that has implications for those who study and measure religious affiliation as well as for church communities themselves.

The insight comes thanks to a weekly survey called the Nationscape, which Democracy Fund began in mid-2019 and stands as the largest publicly available survey dataset in history, with nearly a half million people surveyed.

When asking about religion, survey administrators gave respondents the option to identify as Protestant, Catholic, Mormon, Orthodox, or Christian, among other options for other faiths. It’s the “Christian” response that makes a difference. Surveys typically make people specify a tradition within Christianity. But when given the option to not choose the “Protestant” label, many who attend Protestant churches don’t.

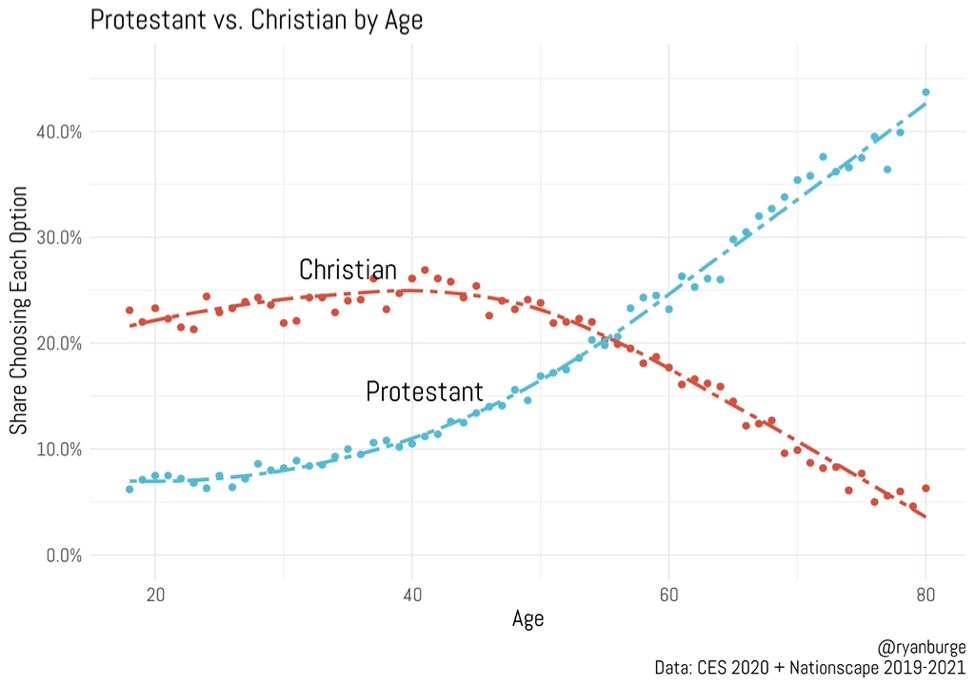

The younger a person is, the more likely they are to prefer Christian over Protestant. Among 20-year-olds, 22 percent indicated that they were Christians, while 8 percent said that they were Protestants. At 40, 25 percent said Christian, and 11 percent chose Protestant. Around age 55, people are just as likely to say Protestant as Christian.

The oldest Americans clearly still identify as Protestant. About a third of 70-year-olds said that they are Protestants, with just 10 percent indicating that they are Christians.

The label “Catholic” seems to be less impacted by age; 18 percent of young folks say they are Catholic compared to 25 percent of folks 75 and older.

While it can be problematic to seek out a causal link for survey findings around religious identity, the shift corresponds to the recent history of Protestant Christianity. The rise of nondenominational Christianity and the decline of the mainline Protestantism began in the 1980s. People who are in their 50s or younger grew up in a world where Protestant terminology was falling out of favor.

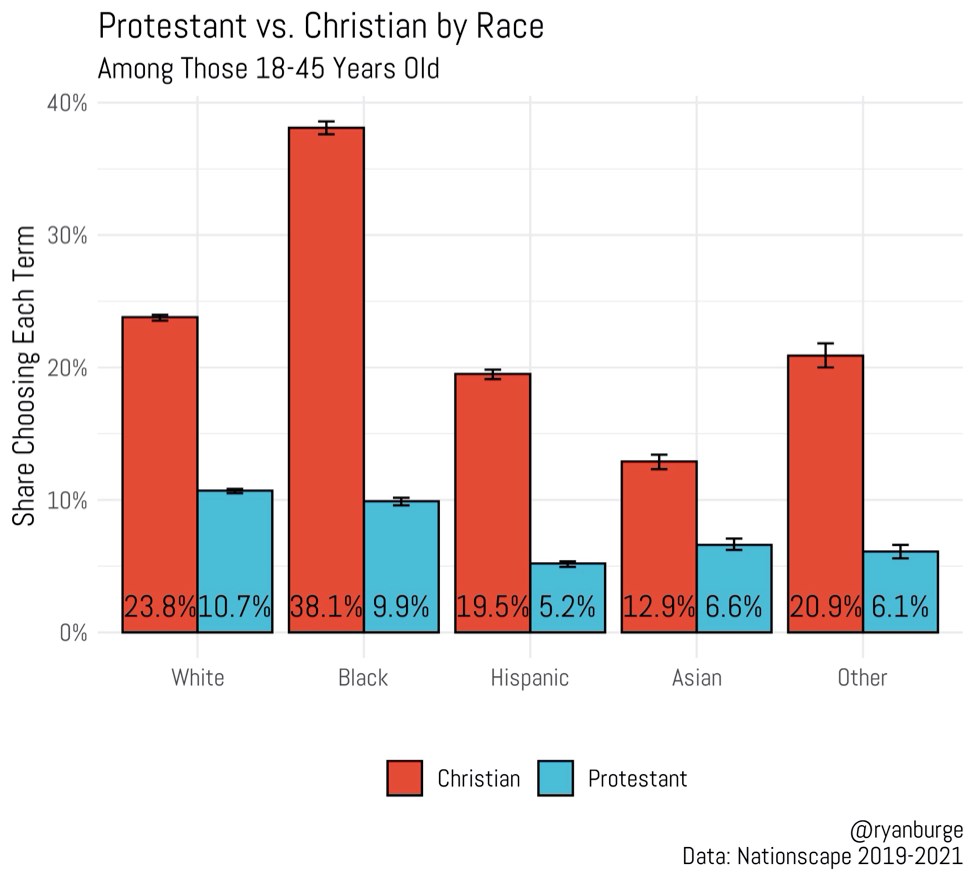

However, race is also a factor in the gap between Protestants and Christians. Among younger Americans, ages 18 to 45, African Americans have the highest levels of religiosity and were more likely than other racial groups to prefer Christian to Protestant. Thirty-eight percent of Black respondents said they were Christians, compared to 10 percent who said Protestant.

Younger Hispanics are also nearly four times more likely to choose the Christian option over Protestant. The gap is smaller among white respondents (24% versus 11%) and those who identify as Asian (13% versus 7%).

In a new paper published last month at the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, I attempted to find other factors around why people hold onto Protestant identity or prefer the Christian label.

The data indicates that those with higher levels of education are more likely to identify as Protestants, but even among younger people with a graduate degree, most prefer Christian over Protestant.

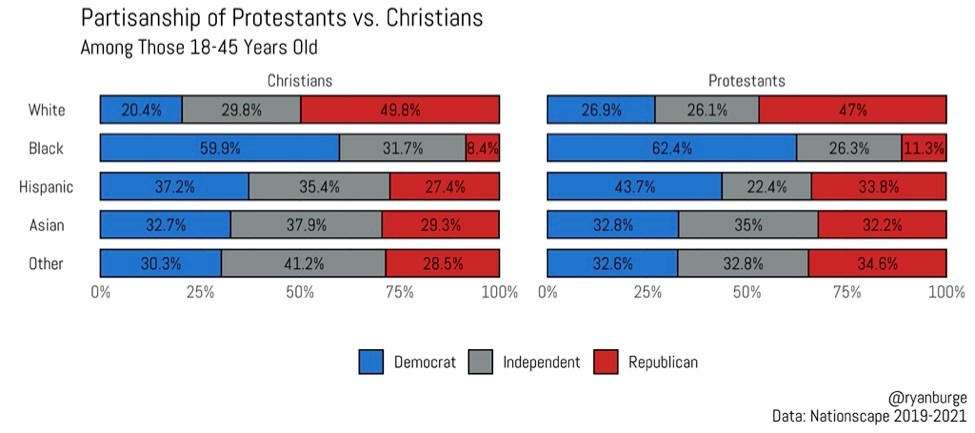

While the Nationscape survey does not include many questions related specifically to religion, it does ask respondents about politics. There is some evidence that younger people who identify as Protestants are more likely to say that they are Democrats than those who say that they are Christians. For instance, 27 percent of white Protestants were Democrats, compared to 20 percent of white Christians. That gap also appears for Black and Hispanic respondents as well.

This may be because churches in the mainline tradition such as United Methodists and Episcopalians, which are more likely to still use Protestant as a label in sermons and literature, tend to be more politically moderate.

I’m a pastor and an academic, and the findings from the Nationscape survey are troubling from both perspectives. Younger Americans don’t seem to have much familiarity with the term Protestant. If surveys continue to ask about Protestant identity—as most still do—and the average American doesn’t understand that distinction, then social scientists run the very real risk of mismeasuring religion.

Fortunately, the overall composition of religion in the Nationscape survey does not look substantively different from other surveys that only include the Protestant option. If Protestants are combined with Christians in the survey, their overall composition doesn’t differ significantly from Protestants in other data. But that may not always be the case.

From a social science standpoint, how people identify (or not) with a religious tradition is incredibly important. One of the key questions that human beings face is “Who am I? And who are people like me?” Religion is one of the ways in which Americans help sort themselves into social space. The Protestant identity helps Baptists, Methodists, and Episcopalians know that they share a great deal of commonality. When those labels begin to fade, there are fewer social signposts to aid people in finding like-minded people.

For churches, a bigger issue may be that many folks sitting the pews may not have any clue about their church’s denominational affiliation or its connection to larger church history. That kind of religious literacy—an understanding of how the basic precepts of their tradition differs from other Christians—can be helpful for understanding their Catholic, Mormon, and Orthodox neighbors, but also for a deeper understanding of the distinctives of their own faith as Protestants.

Embracing a label-less approach to spirituality seems to be the current trend, but as this data indicates, it is having very real impacts on how Americans understand their place in the religious world.

Ryan Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University. His research appears on the site Religion in Public, and he tweets at @ryanburge.

Support Our Work

Subscribe to CT for less than $4.25/month