Jesus loved data. That sounds strange since we often associate data with the rise of modern technology, but in its purest form, data is simply facts or information that can be analyzed for a specific purpose. And it has shaped the life of the church for millennia.

In fact, we can look both to Jesus and the apostle Paul for prime examples of demographic, personal, and religious data informing their approaches to ministry. Consider Jesus’ interactions in Matthew 9:

Jesus went through all the towns and villages, teaching in their synagogues, proclaiming the good news of the kingdom and healing every disease and sickness. When he saw the crowds, he had compassion on them, because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd. Then he said to his disciples, “The harvest is plentiful but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field.”

As he looked upon the crowds, Jesus was gathering data. He was taking stock of people’s needs and desires, their weaknesses and hurts. As he analyzed that information, he felt motivated by compassion to act on their behalf.

Even the apostle Paul, lacking Jesus’ godly insight, was able to gather and utilize information to minister powerfully.

In Acts, “Paul goes to the Jews at Pisidian Antioch and says, ‘Men of Israel, and you who fear God, listen,’” explains Ed Stetzer, the Billy Graham Distinguished Chair of Church, Mission, and Evangelism at Wheaton College. “But when he speaks to the nonreligious in Lystra, he talks about nature, the harvest, and the ocean. And finally, when Paul goes to Athens, he says, ‘People of Athens! I see that in every way you are very religious,’ then quotes their Epicurean and stoic philosophers.

“How did Paul know that in one place he should talk about nature, and in the other he should talk about poetry, and in the other he should talk about Jewish history?” Stetzer continues. “Because he knew people. Fast forward 2,000 years: We have tools to know people in a way that we didn’t have before, and those tools can be quite remarkable.”

What Data Does

Like Jesus and Paul, when we clearly see the needs of people, we must pursue them. Why? Because data inspires action.

“[Jesus] knew their hearts,” Stetzer says. “He knew who they were. As leaders, we too need to know our communities so that we can engage our communities.”

Jesus, of course, has the advantage here; we can’t look at a crowd and know their hearts. But through conversation and regular contact, we do develop an intuitive feel for how best to minister to people. We look into their eyes during the passing of the peace. We read their Facebook posts. We write down their prayer requests. These touchpoints provide us with knowledge and shape the way we serve.

Despite our best efforts, however, our perceptions of people are not perfect. Each of us carry biases and assumptions. We let personalities and dispositions override reality. And, as flawed leaders, we can draw flawed conclusions about who our people are and what they may need.

This, Stetzer asserts, is why the “corrective lens” of data is so essential. Data draws reality into focus. It creates nuance, Stetzer says, and it reveals where our understandings may be skewed or short-sighted.

For example, you may have assumed that millennials, used to 280-character tweets, have short attention spans. Perhaps you let that assumption shape your sermon length as you seek to draw in young families, prompting you to shorten your message.

Data tells a different story. Recent Barna and Gloo statistics show that millennials across four major regions—the Dallas-Fort Worth area, Kansas City, Columbus and its environs, and South Florida—prefer lengthier sermons than Gen Xers or boomers do. In Kansas City, for example, 50% of millennials polled indicated a preference for sermons that lasted 31 minutes or longer; only 38% of Gen Xers and 29% of boomers said the same.

Generalizing is an understandable impulse. We can’t possibly know the internal depths of every person in our congregation, so it’s natural that we draw conclusions about groups based on what we know of individuals. The danger comes in failing to examine our assumptions or when we entirely forget that we’re making them.

Gathering information has the power to release these binds of bias and prejudice. Tools like census records, city-wide forums, and online polls help us overcome our personal limitations and embrace a fuller, more accurate view of our people. Through demographic data, we can begin to ask ourselves how factors like race, education, vocation, socioeconomic status, or gender may subtly distort how we view others.

What incorrect assumptions may be limiting your congregation’s growth and potential? And how might investigating those assumptions lead to more effective ministry?

Knowledge Demands a Response

A few years ago, Brooke Hempell, Barna Group’s senior vice president of research, and her team looked at a dataset focused on Dallas-Fort Worth. They noticed an unsettling contrast: While the city seemed to be flourishing economically and culturally, that trend did not bear out in the African American community. The financial gains many in Dallas were seeing were not occurring within, nor trickling down to, the Black community there.

Hempell points out that this information offers pastors the chance to identify and minister to those who are suffering while also highlighting areas of injustice.

“Data gives them the power to advocate and to make changes that are needed,” she says. Armed with this information, pastors could meet with community leaders to better understand the wealth disparities. They may prioritize faith-and-work conversations in order to educate congregants on the workforce, economy, or housing markets that contribute to these numbers. Or they may preach a series on biblical stewardship and generosity, emphasizing the importance of investing in the local community. We, as pastors, have a responsibility to learn more so that we can do better.

Data Isn’t Mathematical—It’s Personal

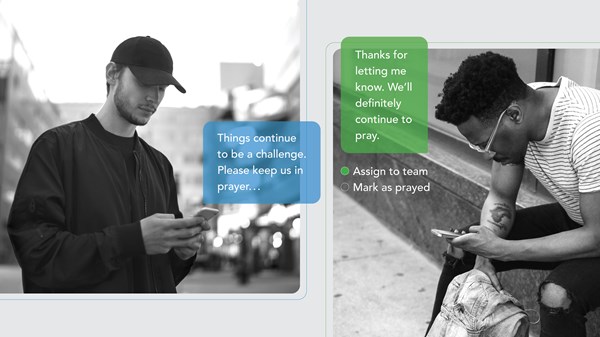

Many assume data is a series of sterile numbers and spreadsheets. But data isn’t mathematical; it’s personal. Gathering this information about your congregation is one of the easiest ways to know their needs and ensure your ministry is meeting them.

Historically, cards in bulletins, potluck lunches, and prayer meetings offered ideas of what a church may need, with foyer chats and hospital visits shaping a pastor’s perspective. In fact, the 17th-century English Puritan church leader Richard Baxter dedicated two full days each week to visiting with the families in his care. He saw getting to know them—compiling data—as a blessing that would lead to greater efficacy in ministry.

With the ubiquity of the internet and social media, data collection has moved from lengthy chats to laptops. Online cookies and uncleared caches now offer companies and brands invaluable insight, helping them identify exactly what kind of lighting fixture, sleep shirt, or shave gel their target market may be interested in. It no longer matters to these companies what “bivocational pastors” as a general category want—far more useful is learning what you specifically want.

As businesses have pivoted from the general to the individual, author and small-church expert Karl Vaters notes, “broadcasting has given way to narrow-casting.” This is, of course, a massive win for businesses that want to see better returns. But is it good for individuals? If the feedback is accurate—yes! Ads, offerings, and services that mirror our true needs can be of benefit to corporations and individuals alike.

This shift prioritizes what marketers refer to as need states—a focus on what an individual person needs in a particular moment. For instance, both middle managers dashing between meetings and students rushing between the classroom and library share the need for a simple snack that’s healthy, quick, and easy to eat. Same need state, two very different demographics.

“There was a reason why demographics targeting a particular type of person worked for a generation,” Vaters says. “Because pretty much everybody who looked like me wanted what I wanted to a surprisingly large degree. That’s not the case anymore. I look around and I see people like me, and they are in totally different need states. We are all in the need state for having a relationship with Christ. But then, we’re all in different places of recognizing that need state.”

What might the needs of your congregants be? What are they lacking that you and your church could help provide? Given our post-pandemic world, it’s likely that many people are facing loneliness, grief, or major transitions. Maybe dating and relationships are top of mind for some of your congregants, whether guys who just graduated high school, single middle-aged women, or those divorcing during their empty nest years. Similarly, financial strain may be shared by the elderly trying to stretch their social security and by the young families living on one income.

When we’re able to identify these shared needs, we can better shape our ministries and resources. For example, many of your congregants may be dealing with lack of closure. They could have lost loved ones during the pandemic, experienced a career disruption, or severed contact with others in the months of social distancing. How might that awareness of your congregation inform your ministry? It has the potential to shape your next sermon series. You could train your small group leaders to help others walk through loss and grief. Or maybe you decide it’s time for church-wide gatherings oriented around socializing, processing, and supporting. Now that you know the need, the opportunities to meet it are only limited by your creativity.

This is the beauty of data: It isn’t a set of rules or a prescriptive list. Instead, this information reveals where boundary lines exist for your congregants. When you know that many of your people share a need—something you may determine through a tool like Gloo’s assessments—you won’t waste time on endeavors that require too much and produce too little.

It’s time to devote your ministerial energy to cultivating fertile ground for spiritual growth according to who, and where, your people are. Like Jesus and Paul, your ministry can be empowered by what you see, your compassion can be stirred by what you learn, and your actions can be motivated by truth. Know your people, pastor, that you might love them well.