Traditional Answers to Troubling Texts: A Challenge

In our previous post about the new book by William J. Webb and Gordan K. Oeste in their new book, Bloody, Brutal, and Barbaric: Wrestling with Troubling War Texts, we mapped out five views. [#ad]

In this post we look at the “traditional” explanations of these troubling war texts, at their weaknesses and strengths, and then we will look briefly at the redemptive movement, or incrementalist approach, for reading these troubling texts.

We began the last post by stating that for some there is no problem to these texts, and this is how they explain them:

The traditional, pristine-ethic “answers” togenocide in the Bible can be summarized as including the following: (1) God as source of the holy war commands, (2) the lofty and good purposes biblical holy war, (3) the noninnocent or evil status of the Canaanites and (4) an understanding of holy war as foreshadowing eschatological judgment (35).

After going through each of these, the W&O find them inadequate to explain the texts in the ancient world, and they instead find square pegs in round holes.

The appeal to God as source of the holy war commands, to their lofty and good purposes, and to the evil character of enemies, much as we might like it to, hardly makes a convincing case that the concrete specific war methodology of Israel’s holy war actions (genocide and war rape) reflects a pristine, untainted ethic. In short, these traditional answers do not connect very well with questions about genocide and war rape.

Nor does invoking the connection in biblical theology between the final eschatological judgment and past occasions of Old Testament holy war alleviate the ethical problems of specific war actions (genocide and war rape) within the biblical text. While the eschatology/foreshadowing solution sounds reasonable because of overarching themes that tie these events together, it fails to account for the differences in particular methodologies between the past and the future portraits, let alone the ethical incompatibility of placing the past elements into the final expression of justice. The actions would have to fit ethically at either end of the holy war continuum for the argument to work.

Yet, W&O think these traditional views do work well for the original context of these troubling texts – even if the traditional explanations fall short for our day.

Their questions were about (1) a land promised by God to Israel, (2) sacred space, and (3) the formation of a New Eden. In the Bible’s larger narrative, the Canaanites become a type of various people groups at various times. They call them “literary” Canaanites and “real” Canaanites. Over and over the experience of the Canaanites resonated with the experience of Israelites being driven from the Land into Exile.

That is, “the God of cosmic holy distance desires to touch our fallen world in order to establish sacred space and intimacy with human beings” (74).

This then is about the holy God who wants sacred space for his holy people and everything unholy is to be removed.

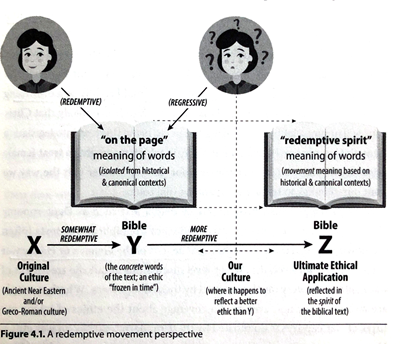

William Webb, over the years, has developed a redemptive movement hermeneutic or what he sometimes (in this book) calls an incrementalist approach to revelation and ethical formation. “0ut it is movement meaning, captured from reading a text in its ancient historical and social context and its canonical context, that yields a sense of the underlying spirit of the biblical text. It is this redemptive-movement or redemptive-spirit meaning that ought to radically shape the contours of our contemporary ethical portrait.

Here is his updated chart:

Jesus Creed is a part of CT's

Blog Forum. Support the work of CT.

Subscribe and get one year free.

The views of the blogger do not necessarily reflect those of Christianity Today.