Is Critical Race Theory a Religion? Responding to Carl Trueman

By Valerie Hobbs

Carl Trueman's article on Critical Race Theory for the February issue of First Things caught my eye last night because of this provocative claim about religious language:

All-embracing and transformative views often have a religious quality. Critical race theory is no exception. It has a creedal language and liturgy, with orthodox words (“white privilege,” “systemic racism”) and prescribed actions (raising the fist, taking the knee). To deviate from the forms is to deviate from the faith. Certain words are heretical (“non-racist,” “all lives matter”). The slogan “silence is violence” is a potent rhetorical weapon. To fail to participate in the liturgy is to reject the antiracism the liturgy purports to represent—something only a racist would do.

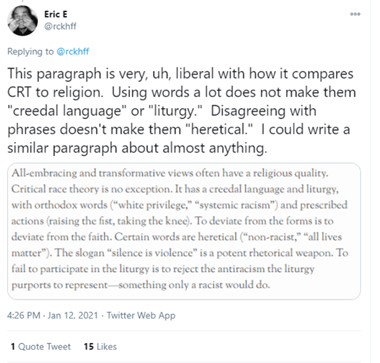

Some have already begun responding to Trueman's argument on Twitter, providing some useful counterpoints. One critic took issue with the idea that anything can be religious. This is too liberal, he argued. "I could write a similar paragraph about almost anything."

See image below and here for the Full Thread

But actually, that is kind of the point. As Edward Bailey aptly put it, not everything is religious, but anything can be religious.

I present extensive evidence in support of this more open perspective on religion in my recently published book called An Introduction to Religious Language: Exploring Theolinguistics in Contemporary Contexts.

Another point of contention I've seen online is Trueman's (predictable) claim that CRT lacks convincing appeals to evidence. The same Twitter critic of Trueman picks this up, arguing that the "overwhelming" data supporting CRT undermines Trueman's 'CRT as religion' thesis.

“They aren't axioms. That's just false.”

Data in support of CRT is indeed overwhelming. One example is the breadth of work from scholars examining disproportionality in child welfare. Another is scholarship on implicit racial bias in healthcare. But both Trueman and his critic rely on a common false dichotomy here, between religion and science. Regarding the presence of data supporting CRT, Professor of Critical Race Studies David Gillborn makes these crucial points:

- Numbers are not neutral.

- Categories are neither ‘natural’ nor given.

- Data cannot ‘speak for itself.’

In my view, Trueman is right to point out that CRT, like all theory, is based on underlying axiomatic principles, including that race inequality is unjust. These axioms guide the collection of relevant data. Again, this is a point I make throughout my book.

But the question remains: Does Trueman make a good case that CRT is, in fact, functioning as a religion? Crucial to his thesis is the assumption that CRT functions as a shibboleth.

Critical race theory (CRT), promoted by progressive activists and adopted by many evangelical intellectuals, has become the shibboleth: Are you for it? Or are you against it?

This is indeed often a sign that something religious is going on, since shibboleths are boundary markers. Trueman develops this by later arguing that those who write about, research and discuss CRT are unwilling to entertain any critique or questions from skeptics.

The theory is likewise hard to oppose, since it denies the legitimacy of arguments that call it into question.

The evidence that Trueman provides is objections to the Southern Baptist Convention's recent motion On Critical Race Theory and Intersectionality. However, sources reporting on disapproval of this motion have revealed that although certainly there are objections to the content of the motion, the problem is more about the fact that it was published at all, especially during such a time of unrest, during which President Trump issued an executive order labeling critical theory "anti-American."

[Jemar] Tisby, the author of the bestselling book The Color of Compromise, referred to critical race theory as the “theological and ecclesiastical equivalent of the ‘Red Scare.’” He said, “Slap anyone with the label ‘Critical Race Theory,’ and they automatically become enemies of the church.”

Kate Shellnut, writing for Christianity Today

We can here draw parallels to the ways that 'feminism' has become a shibboleth within (particularly white) conservative and Reformed Christianity. I have documented this in my own research. So I agree with Trueman that at the heart of all this is the issue of exclusion.

But Trueman neglects major issues of relevance here: the nature of the exclusion (who is excluding whom) and the mechanisms by which it has come about.

This takes me to the heart of my objections to Trueman's article: First, that he has not presented convincing evidence that CRT has its own "creedal language." And second, that his article is actually participating in and even increasing the likelihood that people will perceive CRT as central to their identity (or not) and speak about CRT religiously (either as sacred or taboo).

What do I mean? What makes language religious? Repetition is not enough, as our helpful critical Tweeter pointed out. Within my field of linguistics, like all other disciplines, we have our own insider technical language that we use to refer to key concepts and processes. Scholars working within CRT are no different in that regard. The repetition of certain phrases may signal their significance within a field, but this need not be linked with religious devotion or be central to members' identity.

But Trueman also cites what he calls "a potential rhetorical weapon," the phrase "Silence is violence" which he sees as a form of CRT liturgy. And he points to what he sees as ritual behaviour within CRT: raising the fist, taking a knee.

But are these actions actually prescribed or even customary among CRT scholars?

Trueman provides no convincing evidence for this. Simply saying something is a liturgy doesn't make it so. Calling something ritual behaviour doesn't mean it is. Religious language (what Trueman here calls “creedal language”) is not a matter of opinion. It is a form of discourse whose study requires specialist knowledge and methods.

Are people behaving religiously around CRT? We've certainly seen evidence that leaders within the SBC are doing so, positioning CRT as outside the bounds of the Christian religion, "resulting in ideologies and methods that contradict Scripture." Are those arguing more positively about CRT's usefulness within the church likewise behaving religiously around it? Maybe. Trueman hasn't demonstrated that either way. But there's another problem with Trueman's argument.

Theories like feminist theory and CRT are attempts to ask questions, seek understanding of and propose solutions to problems that institutions, including the Christian church, have tended to overlook and ignore.

There can be no doubt that parts of the Christian church have resisted frank discussions of racism, sexism and misogyny, particularly led by people who've been hurt by this discrimination. Carl Trueman knows this very well, considering he was eyewitness to the recent firing of his colleague Aimee Byrd from the Alliance for Confessing Evangelicals, which took place in the context of sexist bullying and harassment of Byrd after the release of her book on Biblical womanhood. Talk about a shibboleth!

Central to theories like CRT is the understanding that exclusionary behaviour like this is reflective and constitutive of, as Trueman puts it, "systemic evil, false consciousness, and hegemonic discourse." Like feminist theory, Critical Race Theory is a tool to achieve greater understanding of the processes that shape and sustain inequality in society. The most violent racist behaviours and speech do not appear in a vacuum but rather take place within institutions which have desensitized people to racism. Within such institutions, everyday language and ways of behaving foster and act as cultural reinforcers of racism, even its most extreme forms. In his recent book, Something’s Not Right, Wade Mullen explores this phenomenon as it relates to some of the ways abuse is institutionalized in the church.

This is one of the points that Christina Edmondson makes in her reference to 'white Christianity' in her recent article for Christianity Today. She positions this within a much larger dynamic of dominance and inferiority, old as sin itself. Edmondson writes,

Isabel Wilkerson, in her new book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, writes how America’s racism works within the broader and older idea of a caste system.

Unlike Trueman, I find this term 'white Christianity' extremely helpful and humbling. It acknowledges the complex environment that surrounds and supports white supremacist Christianity. It doesn't imply that all white Christians are committed racists. It doesn't suggest that white Christians who neglect self-examination regarding racism are unsaved. Neither does it assert that racism is the only sin within the Christian church. But it does expose what every white American Christian (and elsewhere) must examine within ourselves: We have been acculturated to (implicitly or explicitly) privilege white bodies, white voices, white lives, and this is woven into the fabric of our systems. Again, there's plenty of evidence for this. It's embarrassing to even have to mention such evidence at this point, in the aftermath of white supremacist violence at the US Capitol.

This takes me to my final point. Eventually, victims resist. Oppressed people protest.

When our love- and freedom-empowered design is restricted or oppressed by sin, we are compelled to resist. We cry out. We push back or seek shelter. We strategize and plan. We protest and legislate. We prophesy and lament.

And in such times of unrest, a religious community is forced to reflect on and reassess its borders, its distinctiveness, its core beliefs. Faced with uncomfortable questions, a community can either buckle down or invite critical discussion and reconsideration.

With regard to questions related to sexism and misogyny, I've seen clearly how certain parts of the church police their borders. I've already mentioned what happened last year to Aimee Byrd. I have been called a feminist more times than I can count, most recently by Denny Burk, who finally deleted that label from an online description of me after a lengthy argument of "No, I'm not," "Yes you are." "No, I'm not." "Yes, you are, but I'll delete it." One fellow Christian went so far as to say recently that the nature of my academic work marks me as being "outside the church."

Uncomfortable questions that unsettle the status quo are not tolerated in certain places. The ways people who ask such questions are treated contain these assumptions: You are not a member of Christianity. You are a member of another religion. Go and be with your people.

This is one reason I do not call myself a feminist, though I have benefitted from and use feminist theory in my work and understand why other Christians choose to embrace the label. For what I have come to see is exactly the point Jemar Tisby makes, that language like feminist and CRT can quickly become markers of core identity when they are used as tools of exclusion. This is another phenomenon I talk about in my book. Resisting a label yet insisting that the difficult conversation continue is one way to counter attempts at exclusion.

In summary, if and when Christians are behaving religiously with regard to CRT, viewing it as "all-embracing and transformative," as Carl Trueman puts it, articles like Trueman's and statements like the SBC motion will only make such practice more, not less likely.

But if the Christian church acknowledges its participation in systemic racism, shows eager efforts to repent of and make restitution for its sin, asks questions in sincerity and humility ... If the church stops issuing public statements against tools that fight oppression, ceases its minimizing and stereotyping of oppressed people's resistance, then religious behaviour around CRT and other theories of inequality will be far less likely. When one’s home is a welcoming and loving place, where all are treated with dignity and respect, there is little inclination to look elsewhere.

As for Carl Trueman, he once quipped that he had fallen in love with a feminist and has never been quite the same since. Perhaps he just hasn't found the right CRT scholar?

Jesus Creed is a part of CT's

Blog Forum. Support the work of CT.

Subscribe and get one year free.

The views of the blogger do not necessarily reflect those of Christianity Today.