Jesus and Women: Subversive?

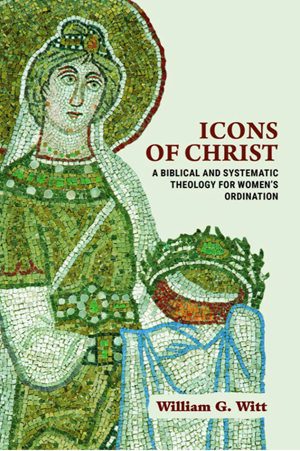

One of the ironies of contemporary discussions about whether or not women should be ordained or not is the role Christ plays in the arguments against women’s ordination. William Witt, in Icons of Christ, offers nothing less than very clever statement about this very issue (my emphasis):

The Catholic and Protestant positions thus provide contrary reasons for not ordaining women to church office. For the Catholic position, women cannot be ordained because they do not resemble a male Christ. For the Protestant position, women cannot be ordained because they do resemble Christ; in the same way, it is claimed, that the Son always submits to the Father, women must always be in submission to male authority.

The Catholic view, which is not the focus of this chp, combines a medieval theory of sacrament with a 1976 major document of the RCC.

Both views have something going for them: looking to Jesus.

At the heart of this chp by Witt is “Christological subversion,” and he anchors the very point in the importance of narrative, of symbol, and of irony and paradox. He works here with Richard Hays. Reading the Gospels ushers us into the world of Jesus where Jesus subverts an honor-shame culture in various ways, including how Jesus treated and related to women.

There is not any doubt that Jesus subverts: he is the Son of God on the cross, he adheres to Moses’ Torah only to radicalize it, he subverts the economic orders, and he is glorified by going to the cross: Mark, Matthew, Luke, John.

He turns to Karl Barth for a kind of both-and: a passive conservativism of culture that entails a radical subversion of that culture: temple, Sabbath, politics, economics, and family. Over and over Jesus upends the categories while walking astride those categories.

The notion of Christological subversion makes clear the radical nature of Jesus’ call to discipleship. On the one hand, Jesus simply accepted and did not challenge the existing social orders of religion, politics, economics, and family. On the other, the freedom of God’s kingdom so transcends all of these orders as radically to call them into question, and this radical challenge to existing order is what eventually led toJesus’ crucifixion as a religious and political subversive.

No one can read the Gospels and not see this tension.

He turns then to honor culture (and here relies on the fine work of David deSilva): it is group oriented, honor-shame oriented, family oriented, hierarchical, filled with slavery and male authority over the household members.

He suggests Jesus worked in this culture and subverted family, the state, and he crossed boundarieds with gentiles and a return to creation for marriage and divorce.

Then he turns to women and Jesus: Jesus and the Samaritan woman, the Syrophoenician woman, the sinful woman, touching unclean women and returning to creation.

I must register some cautions: Witt makes too much of the contrast between Jesus’ relations with women and Jewish culture. The fact is that Jesus is not once criticized for his relations with women. Some will point to the Samaritan woman. But, not only is she now a (mistaken) stereotype but the criticism here is not because she was a woman but a Samaritan. The reality is that one would have an impossible time carrying on in public in Galilee without bumping up against an unclean woman. Most Jews were unclean most of the time! (So, they didn’t go to temple. OK. Wash and wait is the law.) The point is this: Jesus is never criticized for this because his relations with women were ordinary, if at times a bit unusual, but not unacceptable.

We don’t need Judaism as a foil to see that Jesus related to women positively. The best studies on this are by Tal Ilan.

Yet, I agree with Witt on subversions.

He had women disciples (cf. too Acts 9:36 on Tabitha): Matt 12:48-50; Luke 8:1-3, Luke 10:38-42 (he pushes back against Grudem’s reading of Mary and Marthan; we don’t need to overdo “sitting at the feet” but that’s a very significant expression), and women were witnesses of Jesus’ resurrection!

There are two kinds of submission: hierarchical and authoritative, and mutual, and Jesus works with the second (pp. 92-94).

Jesus operated with a new kind of ethic: one marked by servanthood and service. Not authority. No power. Not hierarchy.

The principle of Christological subversion shows that, while Jesus did not set out to overthrow the first-century honor culture, his teachings and actions undermined it.

I agree. There’s sufficient evidence for how Jesus related to women to see something distinctive and paradigmatic.

Ordination at work here? No. That’s anachronistic. But a paradigm is being established.

At the same time, however, the manner in which Jesus’ teaching and mission subverted first-century assumptions about the proper cultural roles of men and women, as well as the way in which he related to women, both strangers and disciples, is relevant to the question of women’s ordination, specifically to the question of whether there is anything about Jesus’ teaching and mission that might count against the practice.

Is there? Witt says no.

The implication of this chapter is that there is not. Nothing in Jesus’ teaching or relations with women implies a permanent subordination of women to men, grounded in a creation order. To the contrary, what he taught about the equality of man and woman in creation would seem to affirm the opposite, and what he taught about servanthood challenges traditional cultural assumptions about authority and power over others rather than affirms them. That Jesus had women as disciples in a manner quite at odds with first-century Jewish culture points in the direction of a challenge to those who would restrict the roles of women disciples of Jesus rather than those who would affirm them.

Jesus Creed is a part of CT's

Blog Forum. Support the work of CT.

Subscribe and get one year free.

The views of the blogger do not necessarily reflect those of Christianity Today.