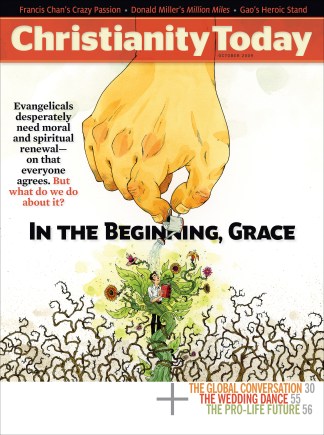

A couple of years ago, I received a flier in the mail:

A new flavor of church is in town! Whether you prefer church with a more traditional blend or a robust contemporary flavor, at [church name], we have a style just for you! Casual atmosphere, relevant messages, great music, dynamic kids’ programs, and yes, you can choose your own flavor!

The “flavors” were described with phrases intended to attract the unchurched: “Real-life messages,” “Safe and fun children’s program,” “Friendly people,” and the marketing coup de grace, “Fresh coffee and doughnuts!”

What pagan could resist?

I poke fun, yes, but I also recognize two realities. First, we must not mock the desire to reach the unchurched. Second, any evangelical worth his or her evangelistic salt has from time to time succumbed to the cultural pressure, in personal conversations or creating outreach programs, to say things that make the gospel seem small.

In our better moments, we recall with the apostle Paul that it is the gospel of Jesus Christ that reaches the world. But we often find ourselves thinking the theology of one character in Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood, who said, “If you want to get anywheres in religion, you got to keep it sweet.”

A New Evangelical Creed

There are various ways that we “keep it sweet”—that is, try to make the gospel inviting to as many as possible. The results have been mixed. Who hasn’t met a new believer who came to faith in Jesus Christ, miraculously, through the most superficial means? For God’s mercy on our often foolish attempts at contextualization, we should be ever thankful.

This doesn’t excuse us from the hard task of self-criticism as we seek to be more faithful. In fact, in the last couple of decades, our self-criticism has practically become an addiction. But it is worth rehearsing some of the more devastating critiques of our movement—both to recall the wonder of God’s mercy, and to put into context our various efforts at reform.

Historian Mark Noll addressed one concern in his Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, writing, “The scandal of the evangelical mind is that there is not much of an evangelical mind.” He was arguing not for mere intellectualism but for a use of the mind that would, in the end, give us a greater vision of God.

Theologian Ron Sider aimed wider in The Scandal of the Evangelical Conscience: Why Are Christians Living Just Like the Rest of the World? Sider was called up short for not clearly defining evangelical and for sometimes relying on questionable statistics, but overall his outrage over evangelical morals and lifestyle is commendable. God forbid that we should ever not be scandalized by nominal Christianity!

And then there are the titles that suggest not just flaws but something much more serious: Frank Viola and George Barna’s Pagan Christianity? and Michael Horton’s Christless Christianity. Yikes!

Such sweeping critiques hinge on what the critic means by evangelical. Some use strict definitions that include a complex set of beliefs and behaviors, and so define evangelicals as a step above the ordinary mortal. Others use loose definitions in which the word seems to mean nothing more than “nice religious person.” Evangelicals by these definitions fare pretty badly when compared with the rest of the world.

In this article, I lean toward the looser definition. We might feel better about ourselves as a movement if we restrict the word to the most committed—that would eliminate the problem of nominalism anyway. But talk to any evangelical pastor of any evangelical church, and they will tell you that the broad definition is what they work with week in and week out: people who think of themselves as “Bible believing” or “born again” or “evangelical” or “saved” and yet, except for the committed few, have beliefs and behaviors that fall far short of New Testament ideals. And if we as pastors, teachers, missionaries, parachurch leaders, and thought leaders—we who write most of the material decrying our movement—are honest with ourselves, we will admit that the enemy we’ve found is often us.

Such critiques are not merely subjective estimates of our spiritual state by a few disgruntled insiders. Our movement has also come under the rigorous scrutiny of sociologists of religion. Their studies confirm our suspicions.

Wade Clark Roof, in his Spiritual Marketplace: Baby Boomers and the Remaking of American Religion, described Christianity in the U.S. as he saw it 10 years ago:” … the drift over time, and still today, is in the direction of enhanced choices for individuals and toward a deeply personal, subjective understanding of faith and well-being.”

When he focused on our movement, he made the same point: “Evidence that the appeal of popular evangelicalism lies primarily in its attention to personal needs, and not dogma or even strict morality, is supported by careful analysis of national surveys. Psychological categories like ‘self,’ ‘fulfillment,’ ‘individuality,’ ‘journey,’ ‘walk,’ and ‘growth’ are all very prominent within evangelical Christianity.”

Many other studies say the same thing, but the most important is Christian Smith and Melinda Lundquist Denton’s Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. Published in 2005, it is already a classic.

Smith and Denton conducted extensive interviews with 267 American teenagers, and concluded that a new religion had emerged in America whose chief tenets are as follows:

- A God exists who created and orders the world and watches over human life on earth.

- God wants people to be good, nice, and fair to each other, as taught in the Bible and by most world religions.

- The central goal of life is to be happy and to feel good about oneself.

- God does not need to be particularly involved in one’s life except when God is needed to resolve a problem.

- Good people go to heaven when they die.

Smith and Denton noticed that this “de facto creed” was particularly prominent among mainline Protestant and Catholic teenagers, “but is also visible among black and conservative Protestants.”

Since the authors found that this faith is learned from parents, they conclude, “We have come with some confidence to believe that a significant part of Christianity in the United States is actually only tenuously Christian in any sense that is seriously connected to the actual historical Christian tradition, but has rather substantially morphed into Christianity’s misbegotten step-cousin, Christian Moralistic Therapeutic Deism.”

This analysis resonates deeply with American evangelical church and parachurch leaders. While Smith and Denton intended to describe the state of teenage faith, they seem to have described large segments of evangelical faith.

‘God Hath A Controversy’

We find ourselves rightly and intensely concerned about our spiritual state, but such concerns are not new. The second-generation American Puritans saw a “declension” in religious fervor, and began adopting strategies to halt the decline. One strategy was the jeremiad, a sermon that rehearsed the sins of the people and the judgment of God, and called for repentance.

When that strategy failed, they gathered church leaders for the Reforming Synod of 1679, which produced a document titled “The Necessity of Reformation.” It said that “God hath a controversy with his New England people” and that he had “written his displeasure in dismal characters against us.”

The Great Awakenings were divine answers to these early pleadings. As much as the evangelistic crusades of George Whitefield, and later, Dwight L. Moody, Billy Sunday, and Billy Graham were meant for unbelievers, we know many Christians attended their events to revive their faith. The rhythm of declension and revival has been a regular feature in American Christianity. We seem to be in another downward part of the cycle as we enter the 21st century.

One reason for this rhythm is this continent’s distinct culture. After his visit to America from late 1831 to early 1832, Alexis de Tocqueville described in eerily contemporary terms two features of American life and the religious tension they produced. While extolling the American emphases on freedom and equality, he said:

It must be acknowledged that equality, which brings great benefits into the world, nevertheless suggests to men … some very dangerous propensities. It tends to isolate them from each other, to concentrate every man’s attention upon himself; and it lays open the soul to an inordinate love of material gratification. The greatest advantage of religion is to inspire diametrically contrary principles. [Emphasis added.]

Tocqueville had the prescience to see the individualism and consumerism that would ever plague American Christianity. But he seems to have had an unwarranted confidence in American religion’s ability to resist these temptations.

Kaleidoscope of Answers

There are other aspects of evangelical nominalism: poor ecclesiology, inattention to doctrine, racism, indifference to injustice, and so on. Because there are so many dimensions, a plethora of movements has arisen to address what each sees as the core issue.

Some of these movements focus on the lack of personal morality, and so champion accountability groups or the spiritual disciplines as the key to renewal. Others attack our individualism and strive to create a church life that is more meaningful, everything from “house church” to “simple church” to “deep church” to “missional church” to “ancient-future church.” Some are most concerned about the lack of spiritual fervor, and put their hope in the Holy Spirit as experienced in charismatic gifts. Some believe we’re not thinking right, and they experiment with new ways of framing the faith, from postmodern theology to new perspective to neo-Calvinism to theology of the kingdom. Some say evangelicals are captive to white culture, and so advocate multiculturalism. Some say we just need to get back to the basics and start following Jesus.

The kaleidoscope of answers—all of them spoken by people who identify themselves as evangelicals—suggests a number of things. First, it suggests that in one respect, the movement is alive and well. We have been from our beginnings a reform movement directed at the nominalism of mainstream Christianity. Now we’ve included ourselves among those who need reform! And in character with our entrepreneurial history and personality, we have launched out in a variety of directions, each movement trying to discern the leading of the Holy Spirit.

For some, such “confusion of tongues” suggests a movement in disarray. There is some truth to that, to which we will return.

For now we should note that the diverse solutions seem to share a common methodology: If evangelicals divorce too often, preach that they should not. If evangelicals are individualist, tell them to be more communal. If evangelicals are privatistic, tell them to get involved in social justice. If evangelicals are worldly, tell them to start practicing the spiritual disciplines. And so on.

In short, we frame the problem horizontally. We focus on what we fail to do, and then talk about what we should do differently. To be fair, such solutions often start with a strong vertical dimension: that is, a sense that we can address the horizontal only by first looking to God.

But our practical and activist sensibility—one of our movement’s stellar attributes—tends to undermine the vertical. This is the problem as I see it at the moment. Let’s note how this is playing out in three of our more impressive sub-movements.

The Spirit of Formation

One of the most promising developments in contemporary evangelicalism has been the re-emergence of spiritual formation, with its emphasis on practices that discipline mind and body so as to open ourselves to the transforming work of the Holy Spirit. Thanks to the pioneering work of Richard Foster and Dallas Willard, the movement has given shape and purpose to the lives of countless evangelicals, saving them from an indolent Christian existence.

The resurgence of interest in the spiritual disciplines began well enough with a strong focus on the vertical. Take Dallas Willard’s now classic The Spirit of the Disciplines: Understanding How God Changes Lives. The title is a play on words and suggests that the disciplines are a gift and grace of the Holy Spirit. The subtitle clearly states that the book is about understanding God’s ways.

But note the shift in emphasis as the genre has developed, with book titles and subtitles that highlight the spiritual disciplines’ horizontal value. They are about the means for “arranging our lives for spiritual transformation” or for “practices that transform us.” One group recently issued a call for Christians to take spiritual formation more seriously. All in all, it’s a positive move. Unfortunately it begins with a paragraph that features the first person plural 11 times: “God calls us … We experience … This lifelong transformation within and among us … We are called … We do not always …” To be fair, the second paragraph highlights the vertical dimension, but what is being communicated if it comes second?

The authors of such books and statements will, in a heartbeat, insist on the divine, gracious nature of the spiritual life. I’m not questioning anyone’s theology or motives. I’m only suggesting that the language we fall into to describe and promote spiritual formation will eventually have an effect. If we continually put the horizontal first, spiritual formation will, as it has in other ages, morph into an oppressive human religion.

The ‘Little’ Problem of the Will

The renewal of social concern also has been an essential correction to the life of the evangelical church. How did we ever forget the legacy of the abolitionists, the prison reformers, the Salvation Army, and others? We can never be too thankful for late-20th-century pioneers in this movement, like Carl Henry, Jim Wallis, and Ron Sider, for calling us to this crucial dimension of the Christian life. The renewal of social concern has turned many Christians and churches from a selfish spirituality to a faith characterized by justice and mercy.

I’ve been following the movement for three decades now—I was an early subscriber to Sojourners and the now defunct The Other Side—and in my experience it has been the rare social justice appeal that grounds itself in the gospel of grace, in the Cross and Resurrection, in the miraculous gift of forgiveness, and in the immense gratitude that naturally flows from that gift.

This relative absence of the vertical—the redeeming work of God in Christ—in social justice rhetoric is matched by a focus on the horizontal. The rhetoric usually assumes that the problem is a lack of human will and that the job of the movement’s leaders is to cajole people out of social indifference with whatever psychological tactic is at hand:

- Guilt: Look at others’ poverty in comparison to our wealth.

- Fear: What will our world be like if we don’t do something about x now?

- Shame: How can we call ourselves disciples of Christ and not do x?

- Moralism: Exhortations littered with should, ought, do, and must.

Sometimes the appeal is less oppressive, but nonetheless optimistic about the human will. A new curriculum designed to help churches love the neighbor—specifically in terms of social concern and social justice—uses this line in an e-mail marketing piece: “For most of us caught up in the hectic demands on our lives, the biggest problem is not desiring to be the Good Samaritan—it’s acting on that desire! It’s starting!” The curriculum promises to solve what it seems to think is a little problem.

The new emphasis on kingdom theology—an eschatological vision that will drive our concerns for social justice—is a helpful vertical corrective. Still, there is optimism in even this corrective that suggests we think all will be well once we get people to think rightly. But the stubbornness of the human will is anything but a little problem. It is, in fact, the problem of fallen humankind, of deep-seated desire gone awry. As Willard put it in a Christianity Today interview, as Christians we are “learning to do the things that … Jesus is favorable toward out of a heart that has been changed into his” [emphasis added]. We cannot simply harangue people to change their wills; our wills need divine attention first.

The more mature leaders of the social justice movement know this spiritual reality all too well. They’ve watched too many activists burn out because they knew not the vertical dimension of social justice. But the language we use to describe our goals and to persuade others can so easily degenerate. The transformation of many liberal churches into social service agencies with a religious veneer is one result of fixating on the horizontal.

Dealing with Cultural Captivity

Another wonderful development is our increased awareness of the variety of races and ethnicities that make up our world. We’re still figuring out what a multiethnic evangelicalism looks like, but no one is arguing that we shouldn’t figure it out! For this we can thank not only America’s changing demographics but also the prophetic voices and examples of men like John Perkins and Rudy Carrasco.

Yet here too we see a constant horizontal temptation. A leading Asian evangelical has just released a book that seeks to “free the evangelical church from Western cultural captivity.” He begins with what everyone recognizes as entrenched problems: our individualism, consumerism, materialism, racism, and cultural imperialism.

But while acknowledging how firmly enslaved we are, the author repeatedly says things like, “Lessons from the black church or lessons arising out of the theology of suffering can lead to freedom from the Western, white captivity of the church.” And in an interview to publicize the book, he says, “In fact, the more diverse we become, Christianity will flourish.”

As if the flourishing of church depends on our ability to make it diverse. As if liberation from the thick chains of cultural captivity is had by learning lessons from others. As if blacks, Asians, and Native Americans are not themselves captive to entrenched cultural ideologies. Missing here and in many such worthy efforts is an emphasis on God’s power, not human example, to free us from the principalities and powers, and on the good news that it is not we who must build the shalom community but the ones who receive it as gift and promise.

Whatever Happened to God?

The same horizontal temptations face any one of us who seeks to directly or indirectly reform evangelicalism. Sider’s subtitle says a lot about what motivates many of us: Why Are Christians Living Just Like the Rest of the World? Similarly, a website that crystallizes the theology and goal of what I call the “following Jesus movement” says, “Following Jesus is about listening and doing. It is about putting into practice the things that Jesus taught. It is about a lifestyle of peace and justice that sets one apart from others” [emphasis added].

In our righteous frustration lies a temptation that entices us when we start anxiously comparing ourselves with “the rest of the world.” This is the temptation of the devout that Jesus described, of the evangelical Pharisee who thanked God that he was no longer like sinners! We might do better to shift the comparison; the scandal is not that we are just like other people but that we are not more like Jesus.

Other examples abound of our temptation to shift our eyes to the horizontal. Take the missional movement—again, a crucial corrective for churches that have become nothing more than religious social clubs. It is a corrective that, in its better moments, focuses on the mission of God. Yet how easily the conversation slides into what we are doing. In an article in which he tried to clarify the nature and purpose of the missional church movement, Brian McLaren defined it as ” … an attempt by Western Christians to reclaim our identity as disciples—people learning to be like Jesus and ready to follow him into our world” [emphasis added].

To be sure, a book title or single remark cannot be used to indict a person or whole sub-movement. Each reform group within our movement has vocal advocates who, while recognizing God’s call to move into the horizontal, nonetheless thoroughly ground themselves in the vertical. Yet the overall impression one gets from self-critiques and studies by sociologists of religion is that we are increasingly uninterested in things vertical. As Wade Clark Roof noted in his study, ” … the ‘weightlessness’ of contemporary belief in God is a reality … for religious liberals and many evangelicals …”

Our Tower of Babel

The plethora of solutions suggests a confusion of tongues. Some say this signals the irreversible fragmentation of evangelicalism. There is no longer an evangelical center, and if there is one, it cannot hold. Many of us fear that we no longer hold enough in common, that we might as well go our separate ways. Not only do we not listen to each other any more, we can hardly understand one another when we do.

Yet even at this crucial moment in our movement’s history, if we stop long enough to listen, we can hear our Lord saying, “Fear not, for I am with you!” The way he is making his presence known clarifies our hope—not only that the movement will survive (which, in the larger scheme, doesn’t matter to the One for whom nations are but a drop in the bucket), but more importantly, in the renewal of God’s people in faith and obedience.

First, we can recognize that God is present in his judgment on us.

It’s easy to point fingers at others, noting how other parts of our movement are dysfunctional: too spiritual, too political, too privatized, or too whatever. But I’ve not met an evangelical leader of any stripe who doesn’t from time to time identify with those first “evangelicals” in Genesis 11, who made bricks and burned them thoroughly, who tried to build a tower of righteousness. We in our various movements are devout and pious, our various missions are godly, our desire is nothing less than to do on earth what is done in heaven, to build “a tower with its top in the heavens” (v. 4a, ESV).

While our various and sundry missions seem vertical, on our better days we know how horizontal we’ve become, how much we’ve done not in the name of Jesus, how much we’ve aspired to “make a name for ourselves” (v. 4b).

It’s never that blatant—we know how to dot our pious i‘s and cross our theological t‘s. But when we presume on the grace of God; when we act as if it is a given and not a daily miracle; when we quickly and thoughtlessly say that “everything depends on grace” and rush on to the real business at hand (what we have to do, and how we have to get other people to do, say, or experience something); when we assume that the problem is merely a matter of the will—we can be sure we are making a name for ourselves and no longer living and doing in the name of our Lord.

Is it any wonder that we reside in the midst of Babel, finding it increasingly difficult to hear and understand one another? I contend that the cacophony we hear is nothing less than the judgment of God. It is not a judgment only against the other parts of our movement, as if our part has learned to live in the grace and obedience of the gospel! Neither is it a judgment only against those Moralistic Therapeutic Deists in our midst, those who need to be reformed to become like us. No, it is a judgment against every strand within the evangelical movement, and every individual therein. It is a judgment against our making the horizontal an idol, against the “weightlessness” of our faith in God.

The place to begin is not more feverish doing, but acknowledging the complete inadequacy of any doing and the utter powerlessness of the horizontal to fix the horizontal.

A Place to Stand

Where the judgment of God is, that is where the mercy of God abides, and where our hope becomes manifest. We stand before God together in both judgment and grace.

Thus, we stand in the place where the cacophony of Babel can become the miracle of Pentecost, when we hear each other again, where we do not see incomprehensible foreigners in our midst but a variety of charisms, callings of the Holy Spirit.

It is where the incessant hectoring and nagging, the doing and striving, can be transformed into acts of love motivated by inexpressible gratitude. It is where our scatteredness can become the fulfillment of God’s mission in the world. It is where the horizontal can become not a denial of the vertical but the expression of it. Where we stand, in short, is Golgotha, under the shadow of the Cross, a sign of God’s judgment on our pretensions and God’s forgiveness of our sin.

This judgment and grace is the word of the Cross, the word that continues to scandalize not only the world, but us too.

The word of the Cross calls us to measure ourselves not against “the rest of the world” but against the righteousness of God. It calls us not to strive and do, but to acknowledge how much our striving and doing is an attempt to justify ourselves, to make a name for ourselves. It calls us to recognize that the problem with evangelicalism is not the piety of the spiritual formation folk, nor the activism of the social justice crowd, nor the ecclesiology of this group or that. No, the word of the Cross says the problem with evangelicalism, to allude to G. K. Chesterton, is me. It calls us not to do more but to cease worshiping idols.

At the same time, the word of the Cross is called folly because it assumes that the vertically-impaired, the horizontally-addicted, the very people whose habits deny the presence and power of grace—especially those who are made aware of and thus grieve their idolatry—are given the grace that makes all things new. Grace makes the horizontal possible in a whole new way.

The One Thing Necessary

The word of the Cross is found, of course, in simplicity and fullness, in clarity and wonder only in the Word of God. That means the living Word, Jesus Christ, the written Word that reveals the living Word, and the preached Word, where Jesus speaks to us afresh (“The one who hears you hears me” [Luke 10:16]). Martin Luther summed it up well when he said, “One thing, and only one thing, is necessary for Christian life, righteousness, and freedom. That one thing is the most holy Word of God, the gospel of Christ.”

This is why the Bible has been central to evangelical life and faith throughout our history, why expository preaching and inductive Bible studies characterize us. Yes, we have often succumbed to bibliolatry. Yes, we often misuse the Bible. Yes, we have a nasty habit of making this means of grace into the weight of law—sometimes even the law of grace! But the Word of God written and preached is first a gift that reveals the crucified Christ, as well as the risen Christ.

In short, it is where the vertical meets and transforms us. When evangelicals have offered the Bible not as a proof text but as the Word that proves and judges and forgives us, that’s when our movement has been transformed and been a transforming agent in the world.

The first thing to do when we confront the dysfunctional horizontal, then, is not to address it as a horizontal problem. That would be to deny the word of the Cross; it would be to pretend we can, of our own wisdom and strength, attend successfully to the problem. The Word of God says the way to start working on the horizontal is to look up, in particular, at the one hanging on the Cross. The place to begin is not more feverish doing but a type of non-doing, acknowledging the complete inadequacy of any doing and the utter powerlessness of the horizontal to fix the horizontal. It means to allow oneself to be borne up by the Word of grace.

At this point, the careful evangelical reader wants to know exactly what that looks like—”What should I do next?” The question is legitimate at one level. It is one we plan to address more specifically in forthcoming issues of Christianity Today. But the righteous desire to do something immediately to fix the problem of the horizontal is itself another symptom of the problem. Sometimes, just when we’re excited about doing God’s work, we are called to first wait, in particular for the judgment and grace of God to become manifest among us again (Acts 1 and 2).

When we meet God in his paradoxical presence, we will once again know that great paradox of the Christian faith: with our focus on the vertical, when the weightlessness of belief becomes for us the weight of glory, that’s when we are born again, born in the Word and for the world. This is something that happens once, yes, at one’s conversion. But it also happens daily, at one’s reconversion each morning and each Sunday. Then we become new creations, blessed with vertical life and energy and grace to do the horizontal thing we are called and gifted to do.

Mark Galli is senior managing editor of Christianity Today. He is author of A Great and Terrible Love: A Spiritual Journey into the Attributes of God (Baker).

Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Books mentioned in this essay include: Wise Blood, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, The Scandal of the Evangelical Conscience, Pagan Christianity, Christless Christianity, Spiritual Marketplace, Soul Searching, The Next Evangelicalism, Why Are Christians Living Just Like the Rest of the World?, and The Spirit of the Disciplines. They are available at ChristianBook.com, Amazon.com, and other book retailers.

This article appeared in the October 2009 issue of Christianity Today with the sidebar, “Preaching as a Vertical Discipline.” A version of that article originally appeared online in 2008.

Previous articles on evangelicalism include:

The Case for Christendom | A renewed sense of Christian culture could be the key to younger evangelicals’ angst. (August 24, 2009)

The Great Evangelical Anxiety | Why change is not our most important product. (July 16, 2009)

Who Do You Think You Are? | The global church needs to ground youth in their true, deepest identity. (February 23, 2009)

Mark Galli writes a regular column called SoulWork. His most recent columns include:

A Pretty Good Religion | Be wary of anyone who starts praising Christianity. (August 27, 2009)

Danger: God | What should we think about a deity who gives us sticks of dynamite to play with? (August 13, 2009)

We’ve Won the Lottery—Now What? | The meaning of evangelical scandals—including our own. (July 30, 2009)