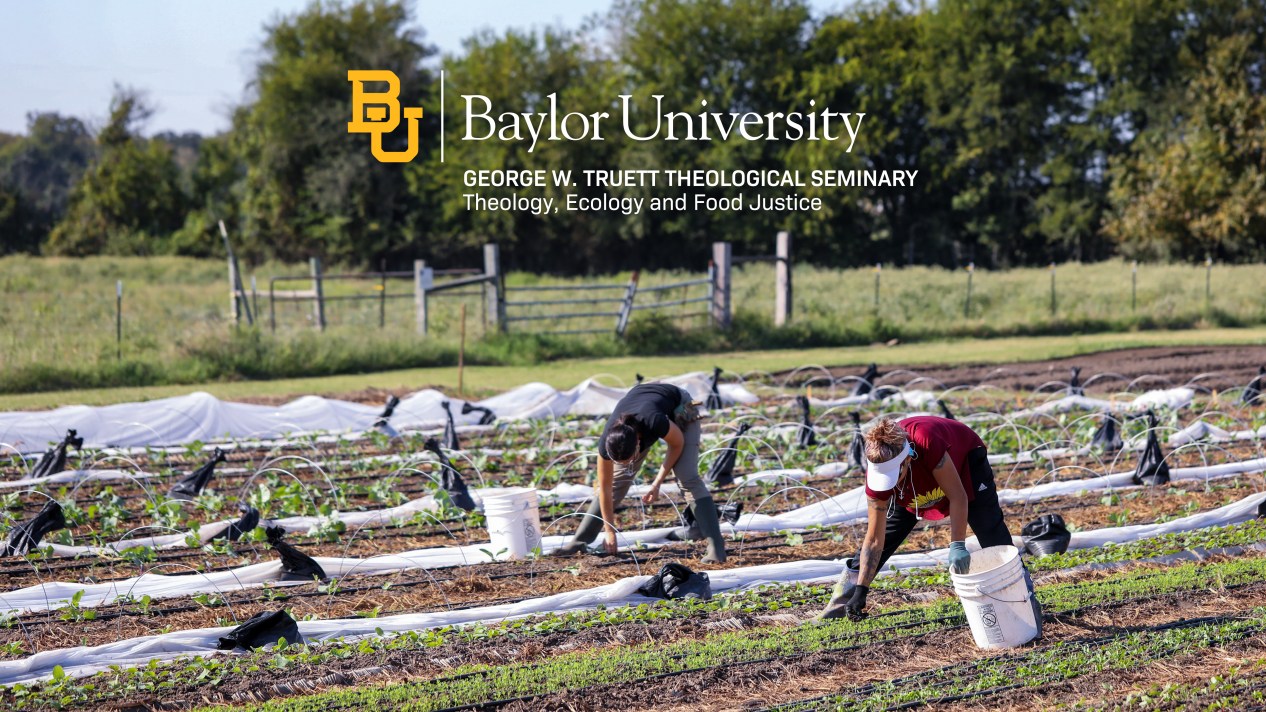

This article is brought to you by Baylor University’s Truett Seminary. Through concentrations like the Theology, Ecology, and Food Justice Program, Truett is equipping Christian leaders to address complex challenges with theological wisdom and practical skills.

The early morning sun warms the soil at Baylor University’s community garden as students gather around Professor Stephanie Boddie. But instead of immediately reaching for their gardening tools, they sit in stillness. Birds chirp overhead, and a gentle breeze carries the scent of ripening tomatoes. This moment of contemplation might seem counterintuitive in a class called “Education from a Gardener’s Perspective,” but it is foundational to how Boddie believes Christians should approach creation care.

“For the first 45 minutes, we’re just being still and understanding who God is and what God has created,” she explains to her three-hour class. “God has created us in community with the rest of creation, and in stillness, we find the kinship in that.”

Initially, students question this practice. Why spend precious class time in silence? But by the semester’s end, transformation is evident. “They tell me, ‘Wow, I’ve changed,'” Boddie shares. “‘I’ve learned how stressed out I was, how distracted. I wasn’t paying attention to the things God was bringing into my sphere. Now I hear the birds’ chirp. I’m actually experiencing the joy and beauty of God’s creation.'”

This contemplative foundation undergirds an ambitious vision: reimagining food systems through the lens of God’s kingdom.

For Boddie, that work begins with discipleship. “We start by understanding our place in God’s created order,” she says. “From that discipleship comes stewardship of creation, care for justice, desire for community building, and cross-cultural reconciliation.”

This vision finds practical expression through the Sustainable Community and Regenerative Agriculture Project (SCRAP) collective in Waco, where Boddie serves as equity facilitator. In a county where 29.8 percent of residents live in poverty, their work is not just about environmental sustainability—it is about embodying Jesus’ prayer: Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.

The transformation is also visible in local congregations. At one church distributing food to 800 individuals weekly, SCRAP helped establish a community garden and training program, empowering people to grow their own food. Another congregation, focusing on diabetes prevention in the African American community, has woven together health education, cultural heritage through African cuisine, and shared meals—all centered around their garden.

“We join people in the work they’re already doing,” Boddie explains. “We listen for what nourishes them—whether it’s their souls, their community, or the work they’re already engaged in.” This approach has led to unexpected flourishing: one church is bringing music to their garden, creating concerts that blend worship with cultivation.

From Local Gardens to Global Fields

This kingdom-minded reimagining extends far beyond Texas. In Sierra Leone, Baylor alumnus Paul Conteh witnessed a startling reality: a nation importing 99.9 percent of its consumable food, despite vast stretches of unutilized farmland.

Drawing on his Baylor education, Conteh founded Agraverse, an agricultural economic development ministry that is transforming communities through sustainable farming. The program has already changed 60 families’ lives in rural northern Sierra Leone’s Tonko Limbo Chiefdom, helping them transition from subsistence farming to growing peanuts as a cash crop.

Like the gardens in Waco, Agraverse’s work is grounded in Christian community. Conteh has built a coalition of Baptist, Wesleyan, and United Methodist churches. “We are working across denominational lines, letting local churches and community leaders shape the program,” he explains. “We want to unify the body of Christ for the good of these communities.”

These initiatives—separated by continents but united in purpose—demonstrate how theological education catalyzes practical solutions to complex challenges. They are also responses to a generation’s growing environmental anxiety. Recent studies show that nearly 60 percent of young people aged 16–25 are worried about climate change, with over 40 percent reporting that these concerns negatively affect their daily functioning.

Debra Rienstra’s concept of “refugia faith” guides this work, emphasizing restoration and renewal alongside the belief that good things can grow even in times of crisis. “How do we, as people of faith, anticipate that restoration?” Boddie asks. “How do we make earth more like heaven?”

As the sun rises higher over the Baylor garden, students move from stillness to action, their hands working the soil with newfound purpose. In this simple act of cultivation, they’re participating in something greater—a vision of God’s kingdom where theological education bears fruit in sustainable solutions, where contemplation leads to action, and where gardens become glimpses of heaven on earth.

Learn more about how the Theology, Ecology, and Food Justice program at Baylor University’s Truett Seminary is equipping the next generation of creation care leaders.

Posted