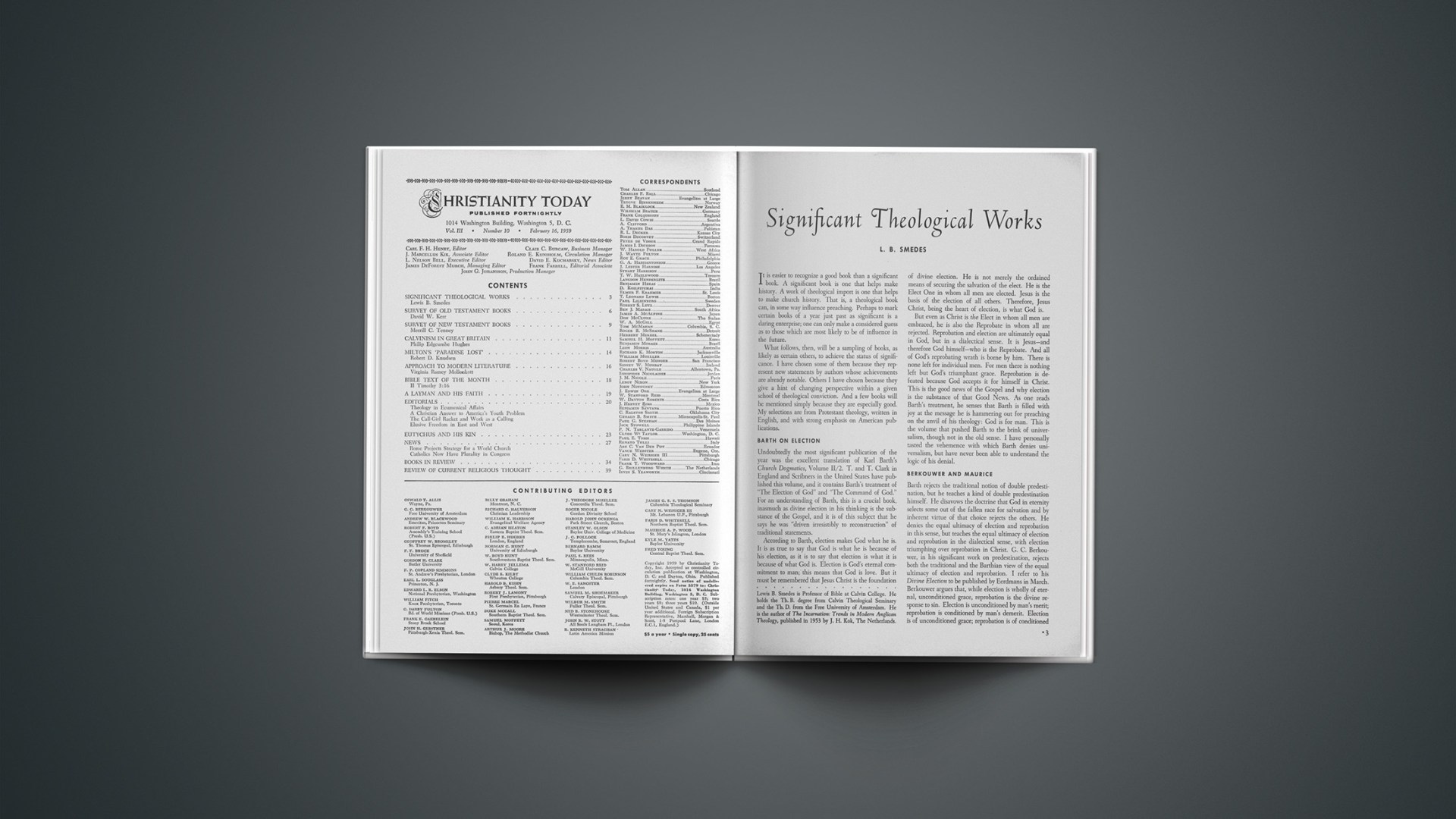

It is easier to recognize a good book than a significant book. A significant book is one that helps make history. A work of theological import is one that helps to make church history. That is, a theological book can, in some way influence preaching. Perhaps to mark certain books of a year just past as significant is a daring enterprise; one can only make a considered guess as to those which are most likely to be of influence in the future.

What follows, then, will be a sampling of books, as likely as certain others, to achieve the status of significance. I have chosen some of them because they represent new statements by authors whose achievements are already notable. Others I have chosen because they give a hint of changing perspective within a given school of theological conviction. And a few books will be mentioned simply because they are especially good. My selections are from Protestant theology, written in English, and with strong emphasis on American publications.

Barth On Election

Undoubtedly the most significant publication of the year was the excellent translation of Karl Barth’s Church Dogmatics, Volume II/2. T. and T. Clark in England and Scribners in the United States have published this volume, and it contains Barth’s treatment of “The Election of God” and “The Command of God.” For an understanding of Barth, this is a crucial book, inasmuch as divine election in his thinking is the substance of the Gospel, and it is of this subject that he says he was “driven irresistibly to reconstruction” of traditional statements.

According to Barth, election makes God what he is. It is as true to say that God is what he is because of his election, as it is to say that election is what it is because of what God is. Election is God’s eternal commitment to man; this means that God is love. But it must be remembered that Jesus Christ is the foundation of divine election. He is not merely the ordained means of securing the salvation of the elect. He is the Elect One in whom all men are elected. Jesus is the basis of the election of all others. Therefore, Jesus Christ, being the heart of election, is what God is.

But even as Christ is the Elect in whom all men are embraced, he is also the Reprobate in whom all are rejected. Reprobation and election are ultimately equal in God, but in a dialectical sense. It is Jesus—and therefore God himself—who is the Reprobate. And all of God’s reprobating wrath is borne by him. There is none left for individual men. For men there is nothing left but God’s triumphant grace. Reprobation is defeated because God accepts it for himself in Christ. This is the good news of the Gospel and why election is the substance of that Good News. As one reads Barth’s treatment, he senses that Barth is filled with joy at the message he is hammering out for preaching on the anvil of his theology: God is for man. This is the volume that pushed Barth to the brink of universalism, though not in the old sense. I have personally tasted the vehemence with which Barth denies universalism, but have never been able to understand the logic of his denial.

Berkouwer And Maurice

Barth rejects the traditional notion of double predestination, but he teaches a kind of double predestination himself. He disavows the doctrine that God in eternity selects some out of the fallen race for salvation and by inherent virtue of that choice rejects the others. He denies the equal ultimacy of election and reprobation in this sense, but teaches the equal ultimacy of election and reprobation in the dialectical sense, with election triumphing over reprobation in Christ. G. C. Berkouwer, in his significant work on predestination, rejects both the traditional and the Barthian view of the equal ultimacy of election and reprobation. I refer to his Divine Election to be published by Eerdmans in March. Berkouwer argues that, while election is wholly of eternal, unconditioned grace, reprobation is the divine response to sin. Election is unconditioned by man’s merit; reprobation is conditioned by man’s demerit. Election is of unconditioned grace; reprobation is of conditioned wrath. They are not equally ultimate in God’s mind. With regard to the eternal decree of God, this view leaves us in imbalance. But Berkouwer does not try to achieve harmony in the eternal mind of God. He insists that he, and we with him, must stop at the limits set by revelation. If logic insists on getting behind the revealed into eternity, it is no longer the logic of Christian theology, but the logic of presumptive speculation. This is probably the most important of the translated works of Berkouwer published thus far. (Another Berkouwer book, Faith and Perseverance, was published by Eerdmans in the spring of 1958.)

There is an interesting parallel between Barth’s doctrine of election and that of F. D. Maurice, the Anglican theologian of the 19th century whose Theological Essays were republished in 1958 by Harper. Like Barth, Maurice viewed all men as elect in Christ and viewed Christ as the eternal basis for God’s decision in favor of man. Also like Barth, Maurice denied universalism. Yet, with Barth, he denied the picture of the separation of the sheep and the goats. This book contains a lot more than the doctrine of election, and Maurice is having a revival of influence in England and America.

Tillich On Faith

Karl Barth once said that faith as such did not interest him. For Berkouwer, too, faith in itself is not enough. Faith is important only in relationship to its object or content. But Paul Tillich’s book of 1958 is an analysis of faith as such. His Dynamics of Faith, published by Harper, analyzes faith as a subjective concern, and it is plain that Tillich considers faith in itself as extremely significant. This book does not, perhaps, carry the weight of Tillich’s Systematic Theology. But it is much more readable than the systematics, and makes clear, as the systematics do not, what Tillich means by faith as “ultimate concern for the ultimate.” The book contains a discerning analysis of the subjective aspect of faith, and much profitable criticism of man’s temptation to place his faith in things less than ultimate, but it misses being a genuine analysis of Christian faith. Christian faith, let us say in Berkouwer’s sense, is idolatry to Tillich. For, with Berkouwer, faith has meaning only as commitment to a Person, and this to Tillich is concern for that which is less than ultimate. Tillich also criticizes the de-mythologizing movement of Rudolph Bultmann as being negative and merely a substitution of a modern myth for an ancient one.

Mythology And Criticism

Scribner’s publication of Bultmann’s Jesus Christ and Mythology gives a rather clear explanation of what demythologizing is all about. Bultmann tells us, for instance, that he does not ask us to reject the mythological elements of Scripture (which include everything supernatural about Jesus), but only to interpret them. That is, he asks us to get the real message which the writers of the New Testament clothed in a mythology no longer capable of being taken literally. He explains the role of existentialism in his theology, denying that existentialism as a philosophy determines his thinking. And he makes clear what he means by the “nowness” of the Word of God. This book should help us judge whether, when Bultmann has removed the “unreal” stumbling blocks from the Gospel, he still has the Gospel.

Gustaf Wingren’s Theology in Conflict: Nygren-Barth-Bultmann, published by Muhlenberg Press, is a well-informed analysis of the principles by which these three theologians interpret the Bible. Wingren concludes that each fails at the starting point of hermeneutics, and that therefore each is led to unbiblical conclusions. Wingren inclines to over-simplify at times, but he has his finger on the pulse of theological controversy at its crucial points, and offers the best monograph of dialectical theology published this year.

Authority Of Scripture

Two small but potentially significant books came from evangelical writers last year. One of them is J. I. Packer’s Fundamentalism and the Word of God, published in paper binding by Eerdmans. Here is a forceful, lucid, and informed defense of the authority of Scripture as understood by evangelicals today. Readers may wonder whether there is not a subtle change of position in it from that, say, of B. B. Warfield. Packer is more willing than Warfield to allow for symbolic elements in such accounts as paradise and the fall. Perhaps more important, the reader may ask whether Packer defends the infallibility (a term he does not relish) of everything written in Scripture or of everything taught by Scripture (cf., for instance, page 169). There is a difference.

Unity Of The Church

The other book is Eerdmans’ publication of G. W. Bromiley’s The Unity and Disunity of the Church. Bromiley works from the important premise that the unity of the church is a reality created in Jesus Christ. Whether church unity is necessary or desirable is not the real question. Unity must be a fact. Churches cannot be neutral towards it. What are the foci around which unity may be visibly expressed? One of them is faith. But Bromiley will not equate faith with a creedal statement to which all churches must subscribe. Faith is man’s response to God’s seizure of him through the Spirit. It is this faith which is the focus of church unity. Another point for unity is the Bible. However, says Bromiley, we may not insist that all churches subscribe to a particular view of the nature of the Bible. Unity around the Bible must mean unity in Christ. Again, Bromiley insists on unity in the truth. But, he warns, this may not mean “unity in our own apprehension of truth.” Our own apprehensions of the truth are always partial. Unity in the truth must mean unity in Christ who is Truth. It would appear that Bromiley is sounding a new note for evangelicals on the subject of church unity, and his book ought to be read with an open mind and a deep concern for the unity of the church.

One other book on the same subject is titled The Nature of the Unity We Seek, a report on the North American Conference on Faith and Order, edited by Paul S. Minear and published by Bethany. The meaty part of the book is found in the committee reports, particularly the report on “Doctrinal Consensus and Conflict.” This report reasserts the sufficiency for membership in the ecumenical movement of the confession that Jesus Christ is “God and Saviour.” Yet it allows every church to supplement and interpret it at will. This freedom to interpret the confession, even in a way that contradicts its biblical meaning, is what offends many non-participating evangelicals. The whole report is significant reading, however, and may well be read for comparison with Bromiley’s book.

Doctrine Of Man And Creeds

Two quite different books on man came out in 1958. One is E. L. Mascall’s The Importance of Being Human, published by Columbia, a lucid, patient effort at restating the doctrine of man in Thomistic, metaphysical terms. Mascall’s thesis, in brief, is that man’s importance must be measured in terms of what he is rather than what he does: man’s being, not his function, is his true significance. The book is a worthy response to the functionalist and existentialist notion of man. The other book is by a psychologist with a theological bent. It is C. G. Jung’s The Undiscovered Self, published by Little, Brown and Company. This one will be used by preachers because of its profound critique of the modern dilemma, and because it points to a religious solution. The individual, lost in a world where things and masses swallow the real man, can recover himself only through a genuine religious experience, only by “anchoring himself in God.” The reader will have to keep asking what Jung means by God and whether Jung’s “genuine religious experience” is meant to be an experience with God or an experience of the basic, unconscious psychic stream that pulsates at the heart of the universe.

One book on historical theology should be mentioned for its sheer excellence. It is J. N. D. Kelly’s Early Christian Doctrines, published in England by A. and C. Black, and issued last month by Oxford in this country. Kelly, who had previously given us a standard work on the early creeds, takes us in this one from the beginnings of theological development to Chalcedon. Kelly’s combination of amazing clarity and exhaustive scholarship can hardly be bettered.

Not theology in the strict sense, but a brilliant penetration of Christian thought into the cultural problems of modern man is Henry Zylstra’s Testament of Vision. Published by Eerdmans under an unfortunately vague title, the book contains some of the most incisive and wise essays written by an evangelical writer in this generation. Christian wisdom informed by learning, disciplined by tradition, and mellowed by love, is brought to bear on man and his world.

Several books deserve more than the brief mention I am giving them here. For instance, Westminster added two books to the Library of Christian Classics: Western Asceticism, edited by O. Chadwick, and Calvin’s Commentaries, edited by J. Haroutunian. Concordia and Muhlenberg continued their great Luther project, giving us Luther’s Lectures on Genesis 1–5 and Church and Ministry II. Baker published Berkouwer’s Conflict with Rome, a patient discussion of theological divide separating Protestants from Rome, a treatment that exemplifies theological controversy at its fairest. Then there are L. Hodgson’s For Faith and Freedom from Harper, being Hodgson’s Gifford Lectures; G. S. Hendry’s The Gospel of the Incarnation from Westminster; and Essays on the Lord’s Supper, by O. Cullmann and F. J. Leenhardt, one of a series of Ecumenical Studies in Worship published by John Knox Press.

There are more books that should be discussed. These at least provide a sampler. The reader will doubtless discover other theological books that to him rank among the significant publications of 1958. But the real importance of what has come from the presses in 1958 will have to be heard from the pulpits of the church in 1959 and years to come. God grant that the theology of 1958 will correct and not corrupt the preaching of the Church in the time our Lord grants us still to preach.

END

Lewis B. Smedes is Professor of Bible at Calvin College. He holds the Th. B. degree from Calvin Theological Seminary and the Th. D. from the Free University of Amsterdam. He is the author of The Incarnation: Trends in Modern Anglican Theology, published in 1953 by J. H. Kok, The Netherlands.

The Multitude of His Mercies

Thy mercies, Lord, a multitude, A never-failing throng, Pursue me now and have pursued My life with joy along. And ever in that multitude I stand in deep amaze; O Lord, though swift to know Thee good, How slow was I to praise!

MABEL LINDSAY