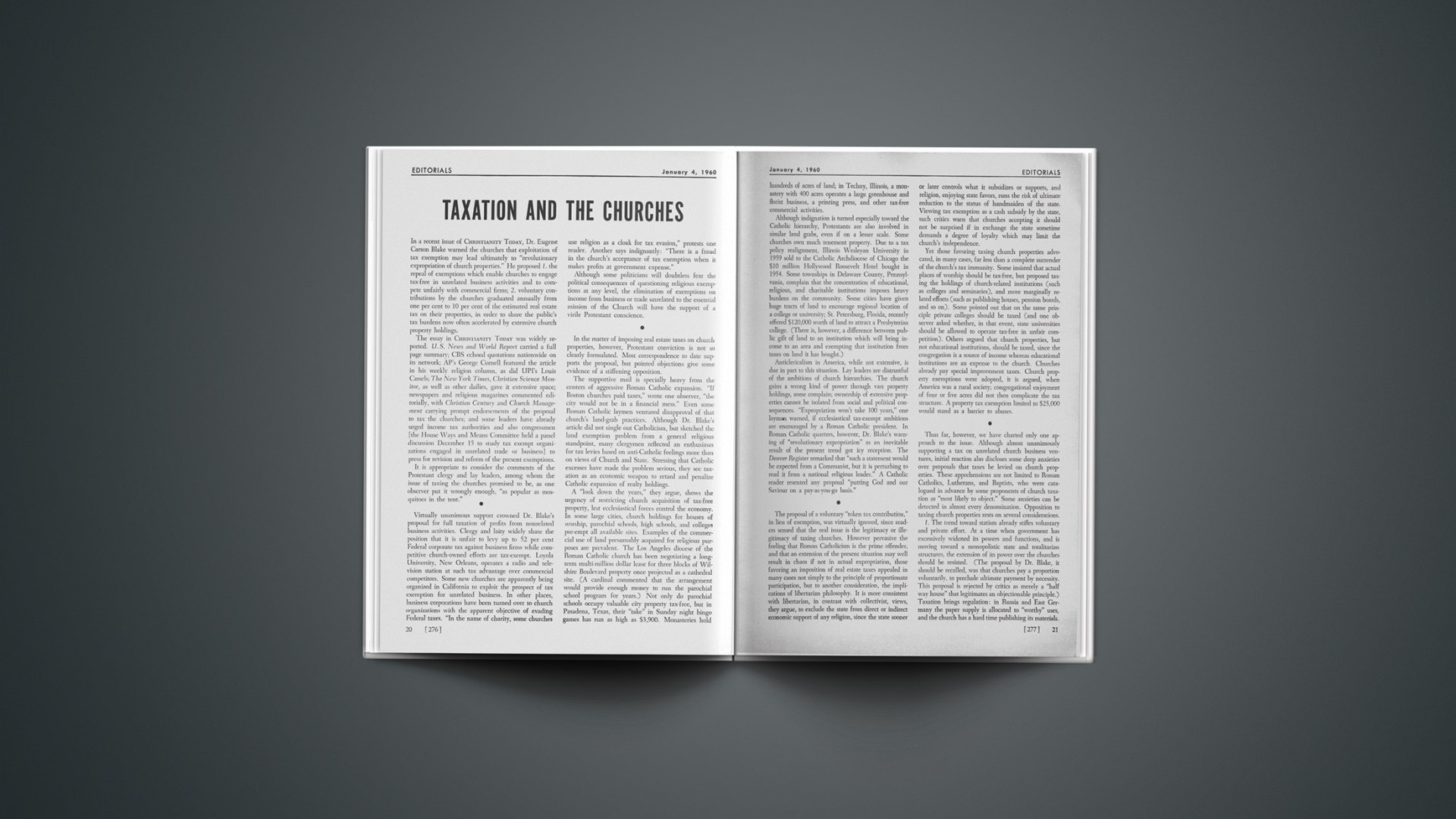

In a recent issue of CHRISTIANITY TODAY, Dr. Eugene Carson Blake warned the churches that exploitation of tax exemption may lead ultimately to “revolutionary expropriation of church properties.” He proposed 1. the repeal of exemptions which enable churches to engage tax-free in unrelated business activities and to compete unfairly with commercial firms; 2. voluntary contributions by the churches graduated annually from one per cent to 10 per cent of the estimated real estate tax on their properties, in order to share the public’s tax burdens now often accelerated by extensive church property holdings.

The essay in CHRISTIANITY TODAY was widely reported. U. S. News and World Report carried a full page summary; CBS echoed quotations nationwide on its network; AP’s George Cornell featured the article in his weekly religion column, as did UPI’s Louis Cassels; The New York Times, Christian Science Monitor, as well as other dailies, gave it extensive space; newspapers and religious magazines commented editorially, with Christian Century and Church Management carrying prompt endorsements of the proposal to tax the churches; and some leaders have already urged income tax authorities and also congressmen [the House Ways and Means Committee held a panel discussion December 15 to study tax exempt organizations engaged in unrelated trade or business] to press for revision and reform of the present exemptions.

It is appropriate to consider the comments of the Protestant clergy and lay leaders, among whom the issue of taxing the churches promised to be, as one observer put it wrongly enough, “as popular as mosquitoes in the tent.”

Virtually unanimous support crowned Dr. Blake’s proposal for full taxation of profits from nonrelated business activities. Clergy and laity widely share the position that it is unfair to levy up to 52 per cent Federal corporate tax against business firms while competitive church-owned efforts are tax-exempt. Loyola University, New Orleans, operates a radio and television station at such tax advantage over commercial competitors. Some new churches are apparently being organized in California to exploit the prospect of tax exemption for unrelated business. In other places, business corporations have been turned over to church organizations with the apparent objective of evading Federal taxes. “In the name of charity, some churches use religion as a cloak for tax evasion,” protests one reader. Another says indignantly: “There is a fraud in the church’s acceptance of tax exemption when it makes profits at government expense.”

Although some politicians will doubtless fear the political consequences of questioning religious exemptions at any level, the elimination of exemptions on income from business or trade unrelated to the essential mission of the Church will have the support of a virile Protestant conscience.

In the matter of imposing real estate taxes on church properties, however, Protestant conviction is not so clearly formulated. Most correspondence to date supports the proposal, but pointed objections give some evidence of a stiffening opposition.

The supportive mail is specially heavy from the centers of aggressive Roman Catholic expansion. “If Boston churches paid taxes,” wrote one observer, “the city would not be in a financial mess.” Even some Roman Catholic laymen ventured disapproval of that church’s land-grab practices. Although Dr. Blake’s article did not single out Catholicism, but sketched the land exemption problem from a general religious standpoint, many clergymen reflected an enthusiasm for tax levies based on anti-Catholic feelings more than on views of Church and State. Stressing that Catholic excesses have made the problem serious, they see taxation as an economic weapon to retard and penalize Catholic expansion of realty holdings.

A “look down the years,” they argue, shows the urgency of restricting church acquisition of tax-free property, lest ecclesiastical forces control the economy. In some large cities, church holdings for houses of worship, parochial schools, high schools, and colleges pre-empt all available sites. Examples of the commercial use of land presumably acquired for religious purposes are prevalent. The Los Angeles diocese of the Roman Catholic church has been negotiating a long-term multi-million dollar lease for three blocks of Wilshire Boulevard property once projected as a cathedral site. (A cardinal commented that the arrangement would provide enough money to run the parochial school program for years.) Not only do parochial schools occupy valuable city property tax-free, but in Pasadena, Texas, their “take” in Sunday night bingo games has run as high as $3,900. Monasteries hold hundreds of acres of land; in Techny, Illinois, a monastery with 400 acres operates a large greenhouse and florist business, a printing press, and other tax-free commercial activities.

Although indignation is turned especially toward the Catholic hierarchy, Protestants are also involved in similar land grabs, even if on a lesser scale. Some churches own much tenement property. Due to a tax policy realignment, Illinois Wesleyan University in 1959 sold to the Catholic Archdiocese of Chicago the $10 million Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel bought in 1954. Some townships in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, complain that the concentration of educational, religious, and charitable institutions imposes heavy burdens on the community. Some cities have given huge tracts of land to encourage regional location of a college or university; St. Petersburg, Florida, recently offered $120,000 worth of land to attract a Presbyterian college. (There is, however, a difference between public gift of land to an institution which will bring income to an area and exempting that institution from taxes on land it has bought.)

Anticlericalism in America, while not extensive, is due in part to this situation. Lay leaders are distrustful of the ambitions of church hierarchies. The church gains a wrong kind of power through vast property holdings, some complain; ownership of extensive properties cannot be isolated from social and political consequences. “Expropriation won’t take 100 years,” one layman warned, if ecclesiastical tax-exempt ambitions are encouraged by a Roman Catholic president. In Roman Catholic quarters, however, Dr. Blake’s warning of “revolutionary expropriation” as an inevitable result of the present trend got icy reception. The Denver Register remarked that “such a statement would be expected from a Communist, but it is perturbing to read it from a national religious leader.” A Catholic reader resented any proposal “putting God and our Saviour on a pay-as-you-go basis.”

The proposal of a voluntary “token tax contribution,” in lieu of exemption, was virtually ignored, since readers sensed that the real issue is the legitimacy or illegitimacy of taxing churches. However pervasive the feeling that Roman Catholicism is the prime offender, and that an extension of the present situation may well result in chaos if not in actual expropriation, those favoring an imposition of real estate taxes appealed in many cases not simply to the principle of proportionate participation, but to another consideration, the implications of libertarian philosophy. It is more consistent with libertarian, in contrast with collectivist, views, they argue, to exclude the state from direct or indirect economic support of any religion, since the state sooner or later controls what it subsidizes or supports, and religion, enjoying state favors, runs the risk of ultimate reduction to the status of handmaiden of the state. Viewing tax exemption as a cash subsidy by the state, such critics warn that churches accepting it should not be surprised if in exchange the state sometime demands a degree of loyalty which may limit the church’s independence.

Yet those favoring taxing church properties advocated, in many cases, far less than a complete surrender of the church’s tax immunity. Some insisted that actual places of worship should be tax-free, but proposed taxing the holdings of church-related institutions (such as colleges and seminaries), and more marginally related efforts (such as publishing houses, pension boards, and so on). Some pointed out that on the same principle private colleges should be taxed (and one observer asked whether, in that event, state universities should be allowed to operate tax-free in unfair competition). Others argued that church properties, but not educational institutions, should be taxed, since the congregation is a source of income whereas educational institutions are an expense to the church. Churches already pay special improvement taxes. Church property exemptions were adopted, it is argued, when America was a rural society; congregational enjoyment of four or five acres did not then complicate the tax structure. A property tax exemption limited to $25,000 would stand as a barrier to abuses.

Thus far, however, we have charted only one approach to the issue. Although almost unanimously supporting a tax on unrelated church business ventures, initial reaction also discloses some deep anxieties over proposals that taxes be levied on church properties. These apprehensions are not limited to Roman Catholics, Lutherans, and Baptists, who were catalogued in advance by some proponents of church taxation as “most likely to object.” Some anxieties can be detected in almost every denomination. Opposition to taxing church properties rests on several considerations.

1. The trend toward statism already stifles voluntary and private effort. At a time when government has excessively widened its powers and functions, and is moving toward a monopolistic state and totalitarian structures, the extension of its power over the churches should be resisted. (The proposal by Dr. Blake, it should be recalled, was that churches pay a proportion voluntarily, to preclude ultimate payment by necessity. This proposal is rejected by critics as merely a “half way house” that legitimates an objectionable principle.) Taxation brings regulation: in Russia and East Germany the paper supply is allocated to “worthy” uses, and the church has a hard time publishing its materials.

2. The tax structure is already excessive and in relation to American tax policy the churches might rather be expected to raise the question of the limits of taxation than to clamor for an extension of it. “There is unjust taxation on private property now—and many inequities,” writes one correspondent. “The power to tax is the power to destroy,” and taxing the churches sooner or later will cripple their financial ability.

3. Those who view tax exemption as a subsidy err in ascribing unlimited powers of taxation to the state; religious exemptions are to be justified not by the favor of the state but by the limits of state powers. The alternate view weakens the doctrine of separation of Church and State.

4. If church properties are taxed, the process will not stop there. Private universities and colleges, philanthropic organizations and foundations, charity and welfare movements, hospitals and homes for the aged, would also come into purview. The Federal government is intruding itself more and more into educational and welfare structures, and already underwrites more research programs than private agencies. The outcome of such a process will be a secular economy with a state welfare ideology.

5. Church taxation would eliminate many struggling churches, especially independent works without access to funds from a central ecclesiastical agency, and ultimately destroy the small denominations. One observer stressed the fact that the suggestions for taxing churches arise not from small denominations, but within large denominations that stand to profit therefrom. Taxation would virtually suspend the expansion of Christianity upon established organizational structures. Even many larger churches will be driven from main corners of our large cities. The church with a Christian day school, or with a mortgage, or lacking funds to pay its pastor an adequate salary, will be crippled, and available missionary and benevolence funds reduced.

6. To favor taxation on churches as an anti-Romanist weapon is reactionary and self-defeating. With the growing political power of Romanism the danger exists that Protestants would be heavily taxed and Romish buildings taxed very lightly.

7. If anticlericalism is feared as a consequence of the wealth of the churches, the problem can be met in other ways than surrendering the right of tax exemption. One reader proposed that churchmen concerned about the problem might begin by giving away half of their own resources.

CHRISTIANITY TODAY thinks the objections are worthy of as much study as the arguments for taxing the churches. At the present stage, tax reforms are worthy of some support, particularly the elimination of exemptions on profits from unrelated business activities. Moreover, if Dr. Blake’s essay has the effect of sensitizing conscience in respect to ecclesiastical land grabs, and provokes some authoritative studies that will place the facts objectively before the American public, irrespective of offending denominations or churches, his ecclesiastical balloon will have escaped preliminary puncture without prematurely prodding us along the precipitous road to state controls as the best way to curtail religious abuses.

ROME AND LICENSE: AN EYE ON THE PRESS

The Vatican spoke last month on the subject of freedom of the press and stuttered in its speech. The Italian newspaper La Stampa and British press agency Reuters reported that Pope John XXIII told Italian jurists that “to protect morals from being poisoned,” freedom of the press should be curbed. Sensing the implications of a blunt bid for censorship, the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano later editorialized that the Pope really sought limitations only “on license of the press.”

One can understand the Vatican’s distress over sexy posters and lurid reporting prevalent in the backyard of the Roman church. But no acute observer will lose sight of Rome’s reliance on compulsion more than spiritual dedication for social change. Nor will he miss the hidden assumption that the Roman church is able infallibly to discriminate what poisons morality, a complaint under which Roman propagandists are not beyond subsuming non-Romanist religion.

CHRISTIANITY TODAY can supply some curious examples of the way Rome’s interest in a “free press” works out. When this magazine was established, its typographer was Walter F. McArdle Company of Washington, D. C., whose head is a distinguished Catholic layman. But this relationship was swiftly dissolved when National Catholic Welfare Conference threatened legal action against McCall Corporation, printers of CHRISTIANITY TODAY, unless the magazine deleted a full page advertisement pertaining to conversion of Roman priests to Protestantism. National Catholic Welfare Conference had unethically learned its contents before CHRISTIANITY TODAY had received its own proofs of the advertisement from the typographers. (Needless to say, CHRISTIANITY TODAY refused to bow to NCWC pressures.)

Another Romish effort to subvert a free press may be cited. If readers will multiply it many times, they will glimpse something of Rome’s pressures on American newspapers. One of CHRISTIANITY TODAY’S editors, Dr. James DeForest Murch, writes an independent column for the Saturday church page of the CincinnatiEnquirer. Recently he wrote of Spain’s religious restrictions on Protestants. Three days before the column was to appear, National Catholic Welfare Conference knew its contents. Then, without consulting Dr. Murch, the Roman Catholic church editor, acting without proper authority from superiors, suppressed the article. When the fairminded Enquirer management learned the facts, the column was reinstated a week later and the article appeared unchanged.

YOUNG LIFE RECRUITING PROVOKES CONNECTICUT CLERGY

Five Connecticut ministers have issued a widely publicized “memorandum to the parents of our young people” warning against efforts of Young Life to recruit high school students. These ministers—liberal rather than evangelical in theological perspectives—depict Young Life as “fundamentally unsound and unhealthy,” as “too narrow,” and in emotional effect “eventually damaging” to young people. The statement bears the signatures of Congregational, Baptist, Protestant Episcopal, Methodist and Presbyterian clergymen from New Canaan, Conn., whose ministers of youth have had moderate success with teen-agers whereas Young Life has rallied students swiftly for evangelistic confrontation of their friends.

Young Life was founded in 1940 by a Dallas minister, the Rev. James C. Rayburn, with headquarters in Colorado Springs. Its 250 clubs gather some 13,000 teen-agers on any given week in off-campus homes throughout the U.S. to bear witness to Christ. In New England, where a staff worker has served about a year, four clubs attract about 200 students in all. Young Life sponsors disclaim launching any new movement, and they solicit no “members.” They do insist, however, that Christian faith be personal and experiential.

Doubtless Young Life has made its quota of mistakes. Although encouraging teen-agers to attend the churches of their choice (some of its own leaders first became interested in church this way), now and then a volunteer worker ties its local efforts to a separatist chapel, or exclusively to some other church in the community. In one instance in Bridgeport, moreover, teen-agers were apparently herded to one Sunday School to help win a national contest.

Nonetheless the New Canaan clergy criticize Young Life from a standpoint of pragmatic weakness, and pay unwitting tribute to its strength. The Christian Way is in fact much narrower than the broad runways of liberal thought. And while ecclesiology doubtless is one element in dispute, critics proclaiming that “the Church is mission” almost inevitably raise counter-questions when they ignore Young Life’s authentic evangelistic concern to introduce teen-agers personally to Jesus Christ as Saviour and Lord.