Before the children arrive for worship, the visitors are properly briefed.

Seizures: there may not be any, but there may be two or three. Don’t be alarmed. The “workers” (there are nine volunteer assistants) will take care of them. Then there is David1At the request of state agencies, name of all children have been changed.. He is apt, in greeting, to throw his arms around your neck. The effort to teach him to shake hands is ongoing, but David enjoys hugging.

You also should be aware that a redheaded teenager named Andrea likes glasses, and may try to rip them off your face.

What else? This will be noisier than the typical church service. And once all the children arrive, the teachers and workers will be occupied. Please do not feel ignored.

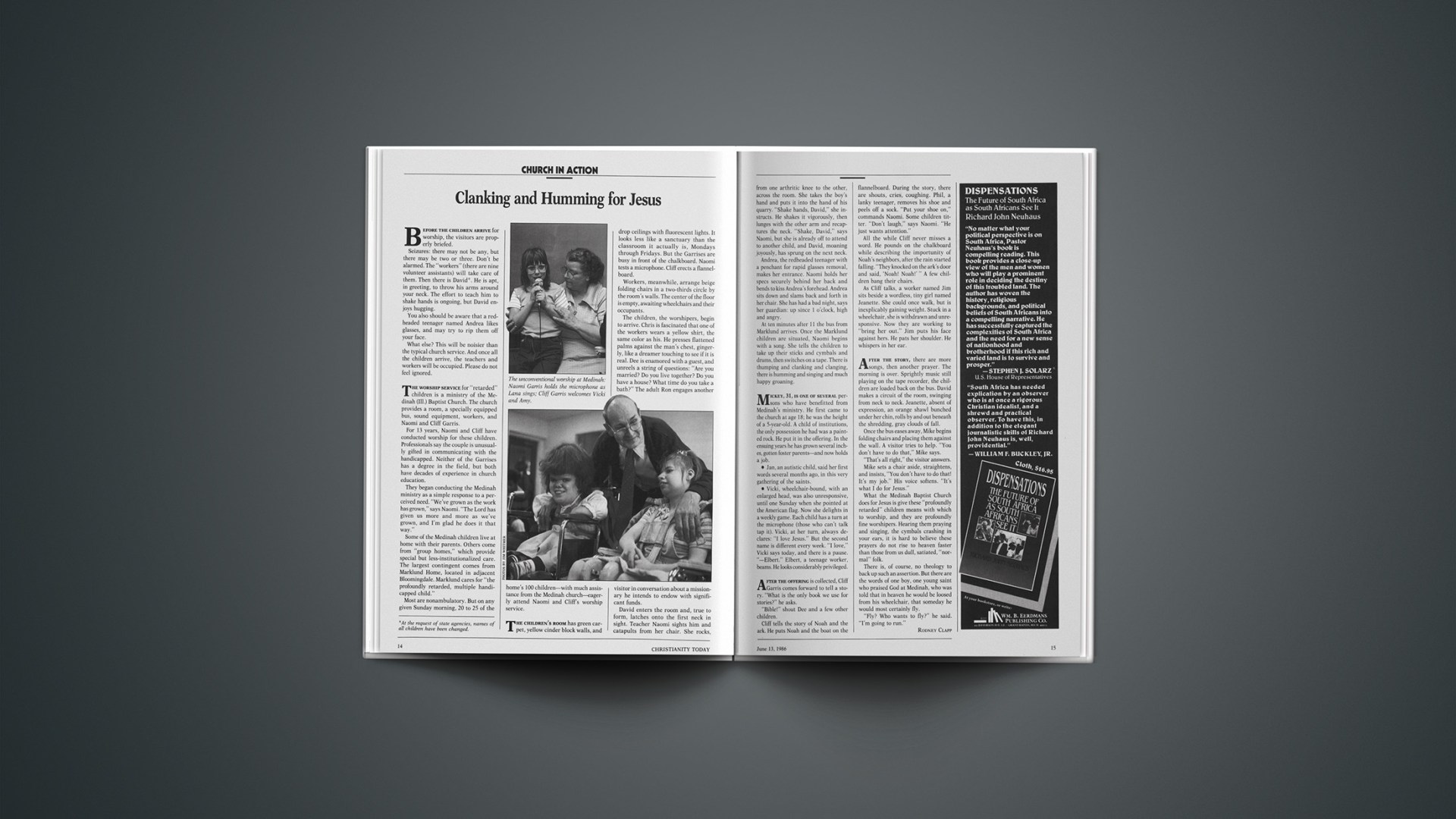

The worship service for “retarded” children is a ministry of the Medinah (Ill.) Baptist Church. The church provides a room, a specially equipped bus, sound equipment, workers, and Naomi and Cliff Garris.

For 13 years, Naomi and Cliff have conducted worship for these children. Professionals say the couple is unusually gifted in communicating with the handicapped. Neither of the Garrises has a degree in the field, but both have decades of experience in church education.

They began conducting the Medinah ministry as a simple response to a perceived need. “We’ve grown as the work has grown,” says Naomi. “The Lord has given us more and more as we’ve grown, and I’m glad he does it that way.”

Some of the Medinah children live at home with their parents. Others come from “group homes,” which provide special but less-institutionalized care. The largest contingent comes from Marklund Home, located in adjacent Bloomingdale. Marklund cares for “the profoundly retarded, multiple handicapped child.”

Most are nonambulatory. But on any given Sunday morning, 20 to 25 of the home’s 100 children—with much assistance from the Medinah church—eagerly attend Naomi and Cliff’s worship service.

The children’s room has green carpet, yellow cinder block walls, and drop ceilings with fluorescent lights. It looks less like a sanctuary than the classroom it actually is, Mondays through Fridays. But the Garrises are busy in front of the chalkboard. Naomi tests a microphone. Cliff erects a flannel-board.

Workers, meanwhile, arrange beige folding chairs in a two-thirds circle by the room’s walls. The center of the floor is empty, awaiting wheelchairs and their occupants.

The children, the worshipers, begin to arrive. Chris is fascinated that one of the workers wears a yellow shirt, the same color as his. He presses flattened palms against the man’s chest, gingerly, like a dreamer touching to see if it is real. Dee is enamored with a guest, and unreels a string of questions: “Are you married? Do you live together? Do you have a house? What time do you take a bath?” The adult Ron engages another visitor in conversation about a missionary he intends to endow with significant funds.

David enters the room and, true to form, latches onto the first neck in sight. Teacher Naomi sights him and catapults from her chair. She rocks, from one arthritic knee to the other, across the room. She takes the boy’s hand and puts it into the hand of his quarry. “Shake hands, David,” she instructs. He shakes it vigorously, then lunges with the other arm and recaptures the neck. “Shake, David,” says Naomi, but she is already off to attend to another child, and David, moaning joyously, has sprung on the next neck.

Andrea, the redheaded teenager with a penchant for rapid glasses removal, makes her entrance. Naomi holds her specs securely behind her back and bends to kiss Andrea’s forehead. Andrea sits down and slams back and forth in her chair. She has had a bad night, says her guardian: up since 1 o’clock, high and angry.

At ten minutes after 11 the bus from Marklund arrives. Once the Marklund children are situated, Naomi begins with a song. She tells the children to take up their sticks and cymbals and drums, then switches on a tape. There is thumping and clanking and clanging, there is humming and singing and much happy groaning.

Mickey, 31, is one of several persons who have benefitted from Medinah’s ministry. He first came to the church at age 18; he was the height of a 5-year-old. A child of institutions, the only possession he had was a painted rock. He put it in the offering. In the ensuing years he has grown several inches, gotten foster parents—and now holds a job.

• Jan, an autistic child, said her first words several months ago, in this very gathering of the saints.

• Vicki, wheelchair-bound, with an enlarged head, was also unresponsive, until one Sunday when she pointed at the American flag. Now she delights in a weekly game. Each child has a turn at the microphone (those who can’t talk tap it). Vicki, at her turn, always declares: “I love Jesus.” But the second name is different every week. “I love,” Vicki says today, and there is a pause. “—Elbert.” Elbert, a teenage worker, beams. He looks considerably privileged.

After the offering is collected, Cliff Garris comes forward to tell a story. “What is the only book we use for stories?” he asks.

“Bible!” shout Dee and a few other children.

Cliff tells the story of Noah and the ark. He puts Noah and the boat on the flannelboard. During the story, there are shouts, cries, coughing. Phil, a lanky teenager, removes his shoe and peels off a sock. “Put your shoe on,” commands Naomi. Some children titter. “Don’t laugh,” says Naomi. “He just wants attention.”

All the while Cliff never misses a word. He pounds on the chalkboard while describing the importunity of Noah’s neighbors, after the rain started falling. “They knocked on the ark’s door and said, ‘Noah! Noah!’ ” A few children bang their chairs.

As Cliff talks, a worker named Jim sits beside a wordless, tiny girl named Jeanette. She could once walk, but is inexplicably gaining weight. Stuck in a wheelchair, she is withdrawn and unresponsive. Now they are working to “bring her out.” Jim puts his face against hers. He pats her shoulder. He whispers in her ear.

After the story, there are more songs, then another prayer. The morning is over. Sprightly music still playing on the tape recorder, the children are loaded back on the bus. David makes a circuit of the room, swinging from neck to neck. Jeanette, absent of expression, an orange shawl bunched under her chin, rolls by and out beneath the shredding, gray clouds of fall.

Once the bus eases away, Mike begins folding chairs and placing them against the wall. A visitor tries to help. “You don’t have to do that,” Mike says.

“That’s all right,” the visitor answers.

Mike sets a chair aside, straightens, and insists, “You don’t have to do that! It’s my job.” His voice softens. “It’s what I do for Jesus.”

What the Medinah Baptist Church does for Jesus is give these “profoundly retarded” children means with which to worship, and they are profoundly fine worshipers. Hearing them praying and singing, the cymbals crashing in your ears, it is hard to believe these prayers do not rise to heaven faster than those from us dull, satiated, “normal” folk.

There is, of course, no theology to back up such an assertion. But there are the words of one boy, one young saint who praised God at Medinah, who was told that in heaven he would be loosed from his wheelchair, that someday he would most certainly fly.

“Fly? Who wants to fly?” he said. “I’m going to run.”