Performing Without a Net

Why I practice the discipline of paper-free preaching Jerry Andrews

No manuscript. No outline. No notes. These guidelines have made me a better preacher.

I wasn't always a paperless preacher. In seminary, I was trained to prepare manuscripts, conditioned to believe that writing out my sermon would help me think more clearly.

My first pastorate shook me. It was a rural church in western Pennsylvania; most of the people were farmers. Fresh out of school, I was eager to share the fruit of my two master's degrees. Within six months, it became painfully obvious that the congregation didn't care for my polished, scholarly manuscripts. I failed to connect.

I consciously began reducing my manuscript to an outline, my outline to a page of notes, my page of notes to a three-by-five card, and my three-by-five card to nothing. The process took nine months, but once I was manuscript-free, it was much easier to engage my people.

Today, I still believe paperless preaching is the best way to nurture that weekly conversation between the preacher, the congregation, and their God. Here's why.

I want to preach, not read.

The pulpit is made for preaching; the lectern for reading. When I am in the pulpit, I need to preach, not read. Preaching is urgent. It is God's Word spoken to my congregation. I want to look people in the eye and change their hearts by reforming their minds. That's less likely to happen if I'm reading to them.

Certainly, an argument can be made for writing out a manuscript and then memorizing it, but I don't know many preachers who can actually do that. What they typically do is write out a manuscript that helps them think through their sermon more clearly. By the time they step into the pulpit, they've abandoned the manuscript because they've now mastered the material. The difference between that approach and mine is that they spend extra time writing a manuscript. I don't.

I want to learn, not cram.

Preparing a manuscript eats up a lot of time that could be better spent prayerfully interacting with the subject. The words of my seminary professor are not lost on me: "One hour in preparation for every minute of preaching." Usually this is considered impractical because it is often understood as "one hour this week for every minute this Sunday." If so, it is poor counsel.

Better to understand it as "much learning before some teaching," or "much knowing before any proclamation." If I have not read, reflected upon, and wrestled with the holiness of God for at least 20 hours, I am not ready to proclaim it publicly for 20 minutes. But I need not do it all the previous week.

Studying only in the week prior to preaching is like cramming, and cramming is the surest way to misspend lots of learning time with the least long-term results. Next week I'll have forgotten what I crammed for this week and be in the same predicament each week for the remainder of my ministry.

However, if I spend those hours reading and reflecting, I'll be in a stronger position each week cumulatively for the long haul. Just as important, if I try to learn most of my subject in just one week, I have no time to test it, relate it, apply it, enjoy it, only enough time to uncritically repeat it out loud. My congregation deserves better.

With the scriptural text as your outline, you become necessarily more dependent on it.

Note-taking is overrated.

If I can't remember what I earlier thought I knew well enough to declare, then I am unprepared. Period. No notes can save me from that. If I know what I am preaching, then I do not need notes.

People ask me if I find myself forgetting points or rambling into tangents as I preach without notes. The answer, of course, is yes.

At my first church, the congregation thrived on the idea that I would deliver a certain number of points, clearly identifiable. They especially liked it if the points rhymed or featured alliteration.

One time I said, "I've got three points," finished my first point, and had no idea what the second one was. So I swallowed my pride and said I couldn't remember number two and went on to the third point, thinking I'd eventually recall the second. But it never came. I'm still waiting for that second point to resurface.

Rambling is also a danger, but it's manageable. An important safeguard is spiritual discipline—learning to keep my ego in check, so that I don't feel obligated to regularly tell folks what I know so that they can know that I know it. What I know is not the point of the sermon. The point of the sermon is to direct people to Christ.

Staying focused on that is no more difficult while delivering a sermon extemporaneously than it is while preparing a manuscript. A manuscript is not a protection from tangents.

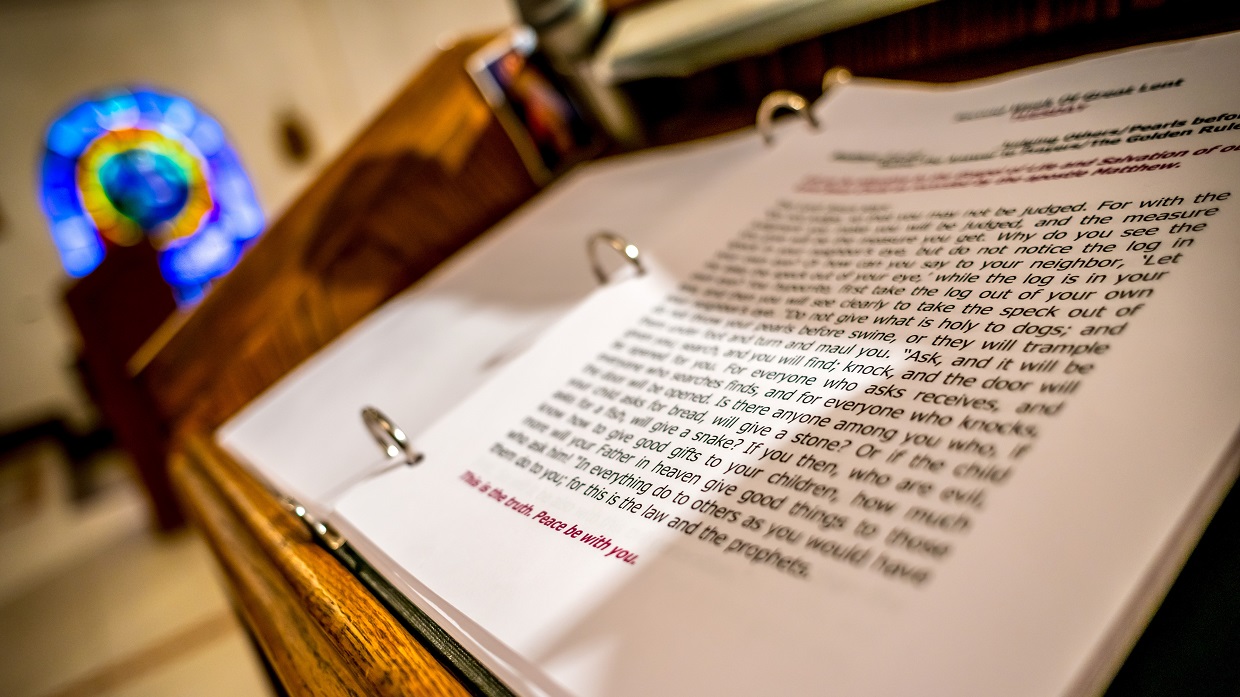

My outline is Scripture.

In one sense, I do have notes in front of me: I have the open Scriptures. If I'm preaching on blind Bartimaeus, I'm open to the passage. That is my outline. I'm going to work through the passage. I'm going to retell the story. I'm going to draw every meaningful conclusion from it that I can, sharing those that are most timely or most significant for my congregation.

With the scriptural text as your outline, you become necessarily more dependent on it. Think of the symbolism of a pastor holding a Bible while preaching versus a pastor shuffling pages of a manuscript.

A manuscript says all the hard work was done in the study, and now it's time to recite the fruits of it. More powerful is to have only the Bible there as a visible reminder that this is where the message comes from.

I want to grow spiritually.

A wonderful side benefit of paper-free preaching is that it keeps me growing. When you step into the pulpit without the aid of a manuscript or notes, you immediately become more dependent on the Spirit of God.

There are times when I do not follow the no-paper-in-the-pulpit model. When I'm preaching or teaching outside my pulpit, I sometimes use notes. If I have only one crack at that audience, and I'm preaching a brand-new sermon, I will often have a three-by-five card of notes in front of me.

Thankfully, though, I usually do have more than one crack at my own congregation. And over time I hope to take them deeper into the conversation with God. Paperless preaching is the best way to do this.

If, after abandoning your notes, you forget a major point, and find yourself standing red-faced before your congregation, just smile and tell them you forgot it. They'll understand. Then begin to monitor their appreciation of the fact that you are talking to them, not at them, above them, or past them.

The test of your success will not be next Sunday's sermon or next month's; it will be a lifetime of excellent preaching.

With the scriptural text as your outline, you become necessarily more dependent on it.

Jerry Andrews is pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Glen Ellyn, Illinois.

Note-worthy Sermons

Why my delivery is better with notes. Paul Atwater

My seminary training left me with one dominant conviction: real preachers don't use notes.

My classmates and I scoffed at the notion of preachers from the Jonathan Edwards era reading their manuscripts. We aimed at being free from the confines of the pulpit, free to gesture, and free to establish unbroken eye-contact with the audience. For us it would be "note-less or bust."

During my final year of seminary, however, one professor, Dr. Jim Means, bucked the "no notes" mentality by giving us a half-hour lesson on using notes when necessary. That lesson has proven to be extremely valuable.

He predicted that many of us would struggle with finding the time to preach without notes. And he was right. Our multiple pastoral responsibilities often turn weekly sermon preparation into a game of "Beat the Clock."

Fifteen years later, I freely confess that I regularly preach from notes. And I believe it has made me a better preacher.

Once in a while I throw out the notes just to prove I can still fly solo, but the benefits of using notes usually win out. Here are four benefits I've realized.

Richer vocabulary, fewer cliches

Sometimes our toughest critics are right. My change to using extensive notes began when my wife handed me a list detailing my favorite expressions, over-used adjectives and the New England slang that I lapse into when speaking without notes.

Listening to a few message tapes proved her right. My wife wasn't the only one who noticed. The bass player in our church band noticed how I frequently used the phrase "truth be told" when emphasizing a key point.

A few Sundays later, the band surprised me with a prelude in my honor entitled "Truth Be Told." We all laughed over that, but I knew I needed to root out this distracting habit.

Writing my way out of this and other cliches was the best way to fix the problem. Today, I find that the more I work at writing, the more likely I am to choose stronger verbs and a richer vocabulary.

Freedom of expression

Well-written notes allow me greater freedom of expression. They eliminate the panic caused by disappearing thoughts, and replace it with greater confidence and ability to deliver the concept I planned.

But make no mistake; there is an art to preaching from notes. If you only use notes when you cannot remember the next point, you're in trouble, and using notes won't salvage your sermon.

The discipline of using notes allows me to find a balance between freedom of expression and word-for-word accuracy.

My notes tell me when to read quotes or transitional sentences as I stand behind the pulpit, and when I can walk away from the pulpit for a needed change of pace, or to establish greater eye-contact while using an illustration.

Since the key to preaching with notes successfully is using them to stay ahead, I glance at my notes while summarizing the points already made, so that I can at the same time prepare myself for what logically comes next.

Better organization

Preaching from notes fosters organized sermons, which in turn helps listeners take notes. Notes also help me use just the right word to explain my point or eliminate my tendency toward poorly-chosen ad-lib expressions or illustrations.

Of course, you must choose what kind of notes you find helpful. One pastor I worked for reduced his weekly research down to three or four sentences on the back of a Sunday bulletin and then turned those sentences into an expository masterpiece of logic and textual clarity, aided by illustrations from his own life.

Another leading preacher operates from a hand-written manuscript, delivered with such clarity that listeners are seldom aware of his notes.

My comfort zone lies between those two. I write my introduction, transitions and conclusion in full sentences, while outlining major movements and sub-points.

Smoother transitions, crisper points

Using notes helps me know when I've made a point effectively and can move on. Bill Hybels refers to well-made points that run on too long as "dieseling."

This habit was exemplified by a beloved pastor with whom I once served, who prided himself in his ability to preach note-free. Unfortunately, his disdain for preaching with notes often left him wandering through sermons, frequently repeating himself.

Preaching with notes allows me to preach conversationally, without being repetitive. Writing out transitional sentences, word for word, helps the message flow coherently from one point to the next.

Finally, well-typed notes allow me to quickly recap main points without relying on cute memory techniques.

Is there an area where your preaching needs work? A mentor once challenged me with these words, "You will only preach as well as you write."

Try writing your way to growth. And take your notes with you.

Paul Atwater is pastor of North River Community Church in Pembroke, Massachusetts.

The Write Stuff

My switch to manuscripts made me a better preacher. Rich Knight

''Our last pastor was considered one of the best preachers in all of Maine," a parishioner at my new church told me. Great. Now my predecessor had reached legend status.

I was nervous enough about the move. After all, I was "from away" as they say here in Maine. I feared that this Pennsylvania native wouldn't be accepted in small-town New England. I tried to tell myself that Maine has never been a hotbed of great preaching, but still, I wondered if I would measure up.

Six months into the new pastorate my wife made a comment that took me off guard: "You know, you're a much better preacher here than you were in Pennsylvania."

Beth has always been my biggest supporter and toughest critic, so I take her feedback seriously. I pressed her to describe the difference. Was it that I had been using all my best illustrations? Was it my choice of sermon topics? Or the newfound energy I felt in a larger sanctuary and a new pulpit?

"It's your delivery," she replied flatly. "Your delivery's much better here."

What was I doing differently here than in my previous 13 years of ministry? I had begun to write out my sermons word for word, and I started carrying my manuscript to the pulpit.

Why I Mac

It all started with the purchase of a computer.

Before moving to Maine, I had preached from notes. Sometimes these notes consisted of outlines with a few verses, thoughts, or illustrations listed under each point. Other times my notes were more detailed, with a few key sentences written out. I never wrote illustrations, and sometimes I would just trust myself to come up with a good ending for the sermon when it came time to wrap up.

The difficulty with this approach is that you have to be at your best all the time. C.S. Lewis made this same point about pastoral prayers. He lobbied for pastors to write out their prayers, trusting that the Holy Spirit would inspire the written prayer during the time of preparation.

Having the computer encourages writing manuscripts. I like typing much more than scribbling on a legal pad, so I don't mind writing sermons word for word. I choose my words more carefully. With the computer I can review the manuscript quickly, looking for phrases that could be made stronger and clearer. It's easy to edit.

Since switching to a manuscript approach, I've had to be careful to avoid term paper language. It's important to write like we talk. Since my normal speaking style is casual and even a bit folksy, I try to write my sermons the same way. This means avoiding words like "moreover," "whereas," and "indeed."

I might have written "In conclusion, one clearly sees" in term papers, but I don't use that in conversation, so I don't say it in the pulpit. Listening to a sermon of mine on tape is a great way to do a language check. Am I using words and phrases I would not normally use if I were sitting around our living room talking with a few friends?

Write it, but don't read it

Preaching from a manuscript has improved my delivery because my work before entering the pulpit forces me to become more familiar with my material. By the time I preach, I have written the manuscript, laid it out in an easy-to-see format, marked it, and memorized large chunks of it.

Of course, it's important to deliver illustrations well, especially personal stories. It looks bad when the preacher says, "I was shopping at the mall this past week," and then looks at the notes to find out what happened next.

I write out my illustrations word for word. Even when I get material from a book or magazine, I retype it into my manuscript. This way I can make word changes if necessary. Little things make a story clear and powerful. Retyping helps me see the details that bring them to life.

Writing out sermon illustrations also helps me practice telling the story. We've all had a story go flat because we didn't tell it well. Or we messed up the punch line. Writing out an illustration helps me set it up and tell it right.

My preaching professor at Princeton, Tom Long, said, "Memorize your sermons a chunk at a time." An illustration is a chunk. A reference to complementary Scripture is a chunk. Introductions and conclusions are chunks. So are transitions. Memorizing these chunks is critical to effective delivery.

This does not take as much time as I feared it would, because, while writing, I have reviewed the sermon on screen a number of times before it's printed.

With my manuscript in a user-friendly style, I can get comfortable with it in about two hours. I preach through the manuscript several times, usually twice on Saturday night and twice on Sunday morning. Then, manuscript in hand, I'm ready to communicate to my congregation what God has prepared me to say.

On a recent Sunday afternoon over lunch, Beth said, "Your sermon was great today. I was a little worried because when I read it on the computer last night it didn't seem that good. But the way you said it, the way you made your points, brought it alive. It was very moving."

A user-friendly manuscript and a bit of practice. These preaching habits give us the tools to look people in the eye and share the Good News.

Rich Knight is senior pastor of First Parish Congregational Church in York, Maine.