To an outsider, Armonía Ministries looks like a remarkable example of local leadership in some of Mexico’s poorest communities—a network of schools, medical clinics, and community centers led by community members themselves. And it is. But Armonía (“Harmony”) is also a cross-cultural mission—not just because it welcomes short- and long-term volunteers from churches in the United States and Europe, but because its founders had to learn to cross daunting class and cultural barriers. Saul (pronounced sah-OOL) and Pilar Cruz founded Armonía in 1987 just as Saul, who holds a Ph.D. in psychology, was rising to prominence as a national leader in World Vision Mexico. As he describes in this interview with Christian Vision Project editorial director Andy Crouch, Armonía’s story is one of unlearning many of his assumptions about success and significance.

|

It’s a story that holds many lessons for anyone who would cross barriers of education and privilege—anyone who is asking the Christian Vision Project’s question for 2007: What must we learn, and unlearn, to be agents of God’s mission in the world?

When you began working with World Vision in Mexico City twenty years ago, how engaged were Protestant churches with the needs of the poor?

In 1985 there were about a thousand Protestant churches—for a city that was estimated at that time somewhat over 8 million people—with an average of 60 members.

We took a socioeconomic map of Mexico City. At that time, 8 percent of the residents of Mexico City were wealthy, some of the wealthiest people in the world, in fact. Then 17 percent, at that time, were middle class; 75 percent were poor, most of them surviving on less than a dollar a day.

Then on this map that highlighted areas by income, we located the churches. Of 1,000 churches, 890 were located in middle-class neighorhoods. A few were among the wealthy—mostly serving not Mexicans but expatriates. Nearly all the rest were at the borders between poor and middle class neighborhoods. Almost none were located within poor neighborhoods.

So you had vast areas of Mexico City without any evangelical Protestant presence.

That must have been a disappointment.

But I did discover a large church in one of the worst neighborhoods—a neighborhood without water, without paved roads, with very little electricity. This is it, I thought, the kind of church that mobilizes its resources to serve in a place where those resources are really needed. So I visited the pastor.

Many churches are little islands that don’t get involved with their neighbors.

Walking into the compound, we found a paradise: green grass, sprinkled water, and nice cars. The pastor received me with great joy, took me to his office, and offered me coffee. He kept a very nice office!

I asked him how in the world his church had ended up here. I was expecting him to say, “I saw the need. I saw that we could have an effect.”

He said, “You know, land is cheap here. If you protect the cars, you can have plenty of good parking spaces!”

What a unique perspective.

Now, I must say that if you come to the United States, the picture is not so different. Many churches are little islands that really do not get involved with the neighbors. They don’t realize that they can have an effect in the transformation of society.

What led you personally into this kind of ministry?

My wife has always been my partner, my chief intercessor. When we got married, we had made a commitment to work among the poor. When I was making very good money and my career as a psychologist was taking off, we had left it all behind to start a school for disabled children in a poor community. But the more I got involved in my work with World Vision a few years later, the more distant she became.

The truth was that while there was plenty of love in our marriage, our postures towards the needy were becoming very different. While I was working on these grand national projects, she had gotten involved with people with cerebral palsy. She was always asking me, “When are you going to join us?” But I was too busy to work with her. After all, I was mobilizing churches to work among the poor!

One day she stopped me and said, “Listen. You’re not the man I married. And I don’t know why you have changed so much. But one of the reasons I married you is because you had this passion for the poor. And now you have a passion to become important.”

“Well, listen,” I said, “If I can influence the churches of Mexico, and if I can mobilize them—”

She said, “Influence the churches of Mexico? Who do you think you are? Luther or Calvin?”

Well. That started a huge conversation.

My wife and I have had those “conversations.”

We took a brief sabbatical and went away to wrestle with this. We fought and fought. Then one day she said: “I don’t want to be mean, but I need to ask you. Do you really know how to work with the poor? Or do you just speak of the poor?”

I didn’t have an answer. I could speak of the poor. I could show you books. I could call the rest of the world to work among the poor. But I personally wasn’t working with the poor.

She said: “We need to learn. And if we don’t learn, how can we call others to do it?”

That ended the argument. She won. Because she was right. We agreed to live in a slum of Mexico City and focus on working alongside the poor.

Now, for my wife, working with the poor was no big deal. She didn’t want to be perceived as a power figure, somebody with access to money or who had an agenda for change, but just a neighbor. But for me, it meant disrobing from my sense of power, my place of safety. I started a little clinic—a place to serve the people and walk my children to school and talk to neighbors. And, oh, that was dreadful, because I was a neighbor—nothing more. Just a neighbor.

It’s not “let’s go transform these poor folks” but “let’s see how they and we will be transformed.”

My wife’s approach, however, was amazingly effective. She connected with prostitutes who wanted to leave their profession, with mothers who had seen their children die because of drug addiction or drug selling, who wanted to change their environment. But I wasn’t satisfied with my wife’s approach. I felt powerless.

When a church nearby offered us the use of their buildings as a community center, I accepted.

Which sounds like a good opportunity.

Exactly. It sounded perfect. We created a community center, and we started bringing people to church there. On Sundays we would wake up early and go to neighbors saying, “Wake up. Let’s go to church. Let’s read the Bible together and sing together. Come join us.” It was becoming a real parade every Sunday. People singing in the streets, knocking on doors, offering coffee to neighbors, some of whom came to church in pajamas!

But I didn’t notice that the church was taking it very poorly. The daughter of one of the leaders fell in love with one of the new Christians, a former leader of a street gang. The father cornered me after a service and said, “If my daughter marries this man, I’m going to kill him.”

Then, one Sunday, I made a huge mistake. As I was preaching, one of the local women we’d worked with came in bleeding, wearing only one shoe. Her dress had been ripped, and she had been seriously beaten—clearly by a pimp. Our little son started to yell when he saw the blood, and grabbed his mommy, so my wife couldn’t go and help her.

No one in the whole room moved toward her. So I stopped preaching, asked one of the deacons to continue the service, and I went over, took her by the hand, and asked my wife to follow me to my office. When we came out, having attended to her needs, the service was over, but a group of church leaders was waiting for me.

“You never abandon the pulpit for a woman like that,” they said. “This is completely out of order!”

I should have known that the relationship was strained beyond repair. But for a few weeks we kept bringing people to church with us. We were usually late, which is not unusual in Mexico. But one week we came singing to the door of the church building. It was locked. This was strange. No one else was there.

I went back home and got my keys. I opened the door, went in—and it was completely empty. Not one chair. Not one bench. Absolutely clean.

They had taken out all the furniture?

Everything. And on the floor was a note: “Saul, we understand that God is leading you in a different way. And we have decided to move. We have bought a piece of land and have built our own church, and you are on your own. If you can pay the bills, you can do it. Good-bye.”

The people with us were crying, cursing, spitting—they felt so rejected by the church. We tried to carry on, but the next morning the owner of the building came. “Are you Mr. Cruz? I need you to vacate the premises.”

I said I was willing to sign a contract. But he said, “No. The people who left said that you keep very bad company, and I should be careful of you.”

“Yes, I’m in very bad company,” I said. “That’s very true. I’m with sinners all the time!”

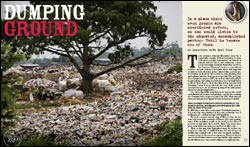

That forced us to go to a piece of land we had been given in the middle of one of the worst slums, a garbage dump. In the lower areas, people were living among the sewage. They made islands in the sewage with dirt and sand and connected them with little bridges, and there was a huge network of manmade islands on top of the raw sewage of the city. We moved to a somewhat safer neighborhood and worked for three years to clean up that property and begin a ministry there. But it was so far from where we had been before that we were starting over entirely. For my wife that was not a problem. She would be happy to start working in the garbage dump.

But for me, it was getting rid of my sources of power more and more.

It sounds like your own sense of significance was stretched to the breaking point.

Exactly. At the end of those three years, I said to my wife, “I need to quit. I want to go back to a regular church. I want to preach again. Here I’m being very ineffective. If you speak, women listen to you. When you read the Bible, women listen to you. They give you their children. You take them to hospitals. Even their husbands come and listen to you. But when I speak, they yawn or they leave. I’m not accepted the way you are. You are extremely effective. I think I’ve got to go elsewhere. I will support you. But I need a better job.”

In my mind, I had become a nobody. I had graduated from university, had won academic prizes, and had a significant career. But in that neighborhood,

I was no one—and it was my fault. I hadn’t learned to speak like them. My wife was speaking like them. I wanted them to understand me, and to listen to my way of speaking. Deep down, I was arrogant, and they could tell.

So I said to my wife, “Look, you’re really the pastor here. I will support you. And I will be the husband of the pastor.” We had such a war that night, a Saturday night. Our poor children had to listen to it all.

“Tomorrow,” I said, “I’m going to start attending another church.”

You’re not the first pastor to have that idea. (Laughter.)

On Sunday morning there was a knock on our door. It was my next-door neighbor, a middle-class man. He said, “Are you a counselor?”

Yes, I said.

“Please help me. I’m losing my marriage.”

I almost told him, “I’m losing mine too—let’s cry together!” But instead, my arrogance crept back in. Here was something I was an expert in! So I invited him in, and we talked for two hours. I was in my element. I felt useful. His wife joined us, and at the end of the conversation, they resolved to find a way to save their marriage. They were relieved and grateful.

Just as they were leaving they asked, “Do you go to church? Because we see you leave every Sunday dressed for church.”

And my wife said, “Yes, we do, and he’s the preacher.”

And I said, “No, no. We have a community center in one of the slums of the city. It’s muddy and smells bad because it’s next to the garbage. And in fact, what I have is a little group of people who come and listen when my wife speaks and don’t listen when I speak.”

The couple said, “We want to go with you.”

“Are you sure?” I asked. But they really did want to go. So they went with us that morning.

At church, as we were in the middle of a prayer, some people came running into the community center to say, “There’s an emergency down at the corner!”

We ran to the corner and discovered that a huge cavern, perhaps eight feet deep, had opened up under the road. A new sewage system had been installed two years before, but it had been not been sealed properly. The sewage coming down the hill was washing away the sand under the road. The road was on the verge of collapse, and there was a danger that dozens of nearby houses would be swept away as well.

Someone called the city services, but they said it would take three days for them to come. It was clear that the road would collapse before then. We had no idea what to do.

Then I felt someone touch my shoulder and say, “Can I help?”

It was the neighbor who had come with me.

“No, no,” I said. “Please, you must get out of here. You are our guest, and this situation is dangerous.”

He said, “No, I know exactly what to do. I’m a mining engineer.”

So he organized the neighbors to make sand bags, and he created a tower underneath the sewer pipes using the sand bags and wood that we took from our own building. We mobilized the whole neighborhood, stopped traffic, and put every man to work. He managed to put everything back in place.

What an extraordinary gift that he had come with you that day!

Of course, it was also an awful mess. We were all completely covered in dirt, and worse. We started working about noon and finished at three in the morning the next day. We emerged from the pit and went back to our community center, probably two hundred men, and the women had heated water for us to wash. They took our clothing, and washed it as best as they could. It was cold and drizzling, and we were shivering, but at least we weren’t smelling as bad as we were before.

And I started to cry. I said, “I’m sorry. But I need to pray. I need to thank God, because he just saved us. He saved you. He saved me. He sent this man, my neighbor, to help us, and he gave us one another to do the work. Can we pray?”

They said yes. So I put out my hands. They held my hands. We all knelt down, and I prayed.

When I stood up, I was their pastor. I could see it. From that day on, they respected me. From that day on, I became their pastor.

You see, being a pastor is about learning the language of love. People need to see you’re for real—that you really care for them, that you’re even ready to put your life on the edge for them. Suddenly my role in that neighborhood completely changed.

Does that story have implications for the way that anyone comes into a poor community?

It’s very easy for missionaries to make the mistakes I made. We build our churches on power. But we never earn the respect of people around us. And with power comes the fantasy that I know it all, that I’m the one with competence to “fix” the society I’m in.

But there’s actually great resistance to people coming into a poor community assuming they know what the people there need. We have realized that when we go into a new community, we have to take the stance that we don’t know anything. We know who we are, we say, but we don’t know how to work here. So we are open. Teach us, please.

When we have groups from North America or Europe visit us, I never have an agenda for the group or for the community. Instead, when the group arrives, we ask the community, “What can you do together? Would you be willing to do something together?” And the answer may be we just want to play football with you, or we’d like you to teach us something about computers. Or it may be, we’re good dancers. Would you like to learn to dance from us?

Visitors say, What? I came to save the world. I came to change the world. My pastor said that we were going to Mexico to change the world for Christ. And you ask me to learn to dance your folk dances?

But you know, they learn much more through this process than just by believing these fantasies that a one- or two-week so-called mission trip will save the world.

What could American churches learn that would help us be better partners for you in your mission?

I think that the American church, which I love and I’m very grateful for, is often not very conscious of its language. You hear the language of “changing the world” from Americans all the time. Well, that has enormous implications for the rest of us! Why do these Americans want to change the world? Into what kind of world will they change it? Do they know better than us? Is that what they mean?

If you come to me, even with the best intentions, and say, “Saul, I came here to change your world,”

I will feel insulted. Because you don’t know how much I love my own culture. I was born here because of God’s decision, not mine. I grew up with our music, our colors, our rhythms.

When people come and say, “Oh, you’re late because this is Mexico,” I always think, Well, so what? Mexicans are laid back. And we love it!

And the same applies when I, as an educated person, go into the slums. When I talk to them, I have to do it locally, on the streets, in their homes, wherever. And I need to be sure we are creating a language of mutual understanding. We need to agree which things we need to focus our attention on changing, and for which things we can just say, “Thank you, God. What you have given us is beautiful as is.”

Then, suppose we agree that one of the problems to address is that children are failing in their English classes. Now it would be easy to say, “Can I recruit someone from England or America to come and teach?” But first I should ask, “Is there a resource in the community?”

Someone may say, “My daughter studies English and she’s doing well. She could teach the children.” But perhaps she needs to work to support herself. Can the community band together to pay her? This kind of process is very different from coming in to “change the world.” We don’t want our neighbors to perceive us as their saviors—they should see us as their partners, their facilitators, their friends.

We pray, “Your will be done on earth as in heaven.” Doesn’t that imply changing the world?

I would distinguish between “change” and “transformation.” Change can come as a result of power. If you have power—the power of superior resources, technology, knowledge, or connections—you can bring a certain kind of change. But if you use power to put what you have down the throats of people, you never, never see them transforming. Instead you’ll see them adapting. But there’s something about “transformation” that implies a process that’s not done to someone, but a process where we both start to create a new common language, a new common world, new common understanding.

So the transformation that needs to take place goes both ways.

Exactly. It’s not “Let’s go transform these poor folks” but “let’s see how they and we will be transformed!”

I don’t at all want to suggest that Americans are not needed in Mexico. We need more of these relationships of mutual transformation. Mexicans feel so neglected, so despised sometimes by their American neighbors.

To see Americans digging alongside them, visiting in their homes, bringing Christmas gifts, sitting with them and giving them some attention, asking about the children—every year remembering their names—makes them believe that God has a community of believers who really care.

That’s the strong language of love.

Copyright © 2007 by the author or Christianity Today/Leadership Journal.Click here for reprint information on Leadership Journal.