Anyone who ever made it in the entertainment business got there because of some “big break.” But do these breaks happen because of luck? Or talent? Or both? In Me and Orson Welles, directed by Richard Linklater (Waking Life), we witness the early days of one of Hollywood’s most successful icons and can decide for ourselves whether luck or talent plays a bigger role in his success.

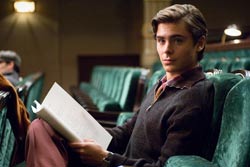

This movie tells Welles’ story through the eyes of a wide-eyed high school student named Richard (Zac Efron) who, in 1937 New York, stumbles into a small role in a production of Julius Caesar that Welles (Christian McKay) is staging in his newly formed Mercury Theater on Broadway. The film is a sort of behind-the-scenes look at the wild world of theater in general, and particularly the even wilder world of Welles—a womanizing, narcissistic, magnetic force of American nature destined for greatness. Richard is in over his head, for sure, and next to Welles he’s about as embarrassingly minute as Miley Cyrus would be if she starred in a film opposite Judi Dench.

Perhaps that’s why, when Richard goes head-to-head against Welles over a woman (Claire Danes) later in the film, it’s hard to root for Richard’s success. He’s outmatched in every way by Welles, and even if he is more virtuous and less tainted by ruthless ambition, he’s painstakingly boring by comparison. But maybe he’s just young. How interesting can a high school teen be, anyway?

None of this is Efron’s fault. The former Disney Channel/High School Musican star is perfectly fresh-faced and innocuous in the part, and he capably embodies the sort of “aw shucks, mister!” vibe of a raised-in-the-Depression New York youth. But Efron can’t help the fact the film’s real star—the British actor Christian McKay as Welles—is infinitely more compelling to watch. McKay, who looks impressively similar to man himself, perfectly captures Welles’ thunderous bravado and penchant for the melodramatic. Though at times it might tilt a little too far in the direction of caricature, McKay’s portrayal is for the most part dead-on.

As for the rest of the cast, Danes is a standout as an eager-beaver member of the Mercury company who will do anything (and sleep with anyone) in order to get ahead. On the soul-deadening ambition scale, she’s somewhere between the innocence of Richard and the ruthlessness of Welles. So perhaps it makes sense that she’s romantically linked with both.

The story plays out against the “clearly a set” backdrop of 30s-era Manhattan, though the majority of the film was shot inside the Gaiety Theatre on the British Isle of Man (and indeed, most of the cast is British too—largely the Royal Shakespeare Company). The visuals are magnificent, to be sure, but at times the film feels a tad claustrophobic and stagey. It’s all so blocked and clean and colorful, when the messy, black-and-white New York of that era might seem a more logical fit (and cheaper too). But Linklater’s stylistic choices are doubtless all very intentional.

Linklater’s films are often heavy on dialogue and slight on action (though this isn’t necessarily a bad thing). Before Sunrise, Before Sunset, Slacker, and Tape are made up entirely of conversations: Just people talking and walking and waxing philosophical. These films put the spotlight on the question of what cinema is and how it differs from theater. If it’s just people talking, why not just write it as a play? What are the benefits of playing for the camera’s eye as opposed to the theater-going audience’s attention? Me and Orson Welles—a movie about theater, focused on an iconic film director—asks these questions with appropriately theatrical gusto.

Linklater and cinematographer Dick Pope (Happy-Go-Lucky, Vera Drake) playfully draw attention to the cinematic presence of the camera. Though we are watching “theater,” our point of view is not fixed as an audience’s might be. Rather, the camera is constantly moving, swooping hither and yon, getting up in the face of the actors. Liberal use of tracking shots, slow zooms, and other “this is what a camera can do!” tricks (including some mise en scene depth-of-field setups Welles would have liked) make a point to underscore the filmic reality of this otherwise theater-centric story.

This is also a film about storytelling and how it lives and breathes in different media forms. Welles is a movie (Linklater) based on a book (Robert Kaplow) about a film director (Welles) who once adapted a Shakespearean play (Julius Caesar) based on a real event. It’s a film about the amorphous versatility of storytelling. It’s not a coincidence that the film is set in the 1930s—a time when the cinema, theater, radio, and newspapers were enjoying their heyday. Back then, people had the patience for things like Shakespeare, the imagination for things like radio melodramas, and the motivation to slow down and read fiction once and a while.

But even in this age of iPods, Twitter and High School Musical, there is still a market for a well-told story. And that seems to be the point Linklater is trying to make. Despite his faults, Orson Welles was a great, ambitious, groundbreaking storyteller. He didn’t care what people said or what obstacles got in the way of his vision. He pressed on and trusted his aesthetic instincts, though sadly he’s as much a relic of the mid-century as he was an anomaly within it (a distinctive voice working within the clone-friendly Hollywood studio system). Do they make them like Welles anymore? Probably not.

At the end of the day, Welles is a movie for people who love Orson Welles or love movies about theater. It has less to say about art, luck, and talent than you’d think it would (for a film so aesthetically self-aware), and it has fewer insights into Welles himself than it probably should. It’s no Citizen Kane, and it won’t change your life. But it’s a well-told story, and sometimes that’s enough.

Talk About It

Discussion starters- What do you think Richard learns about “luck” by the end of the film?

- Is there any significance to the Julius Caesar “play within the movie” motif?

- What does Richard learn from his experience in the Mercury Theater? What is the biggest lesson?

The Family Corner

For parents to considerMe and Orson Welles is rated PG-13 for sexual references and smoking. It’s fairly clean for PG-13. There are a few scenes of implied sexuality, some scenes of drinking and smoking, and a general spirit of amorality (e.g., characters like Orson Welles cheating on spouses), but in general it’s pretty safe for families and teens.

Photos © Freestyle Releasing

Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.